MONTREAL -- Fast radio bursts have been a cosmic mystery ever since astronomers first detected the extragalactic pulses about a decade ago.

They're flashes of radio waves lasting less than a thousandth of a second coming from far outside the galaxy.

Nobody knows what they are and where they come from, but new research done partly at Montreal's McGill University solves a piece of the puzzle with the suggestion the phenomenon can repeat.

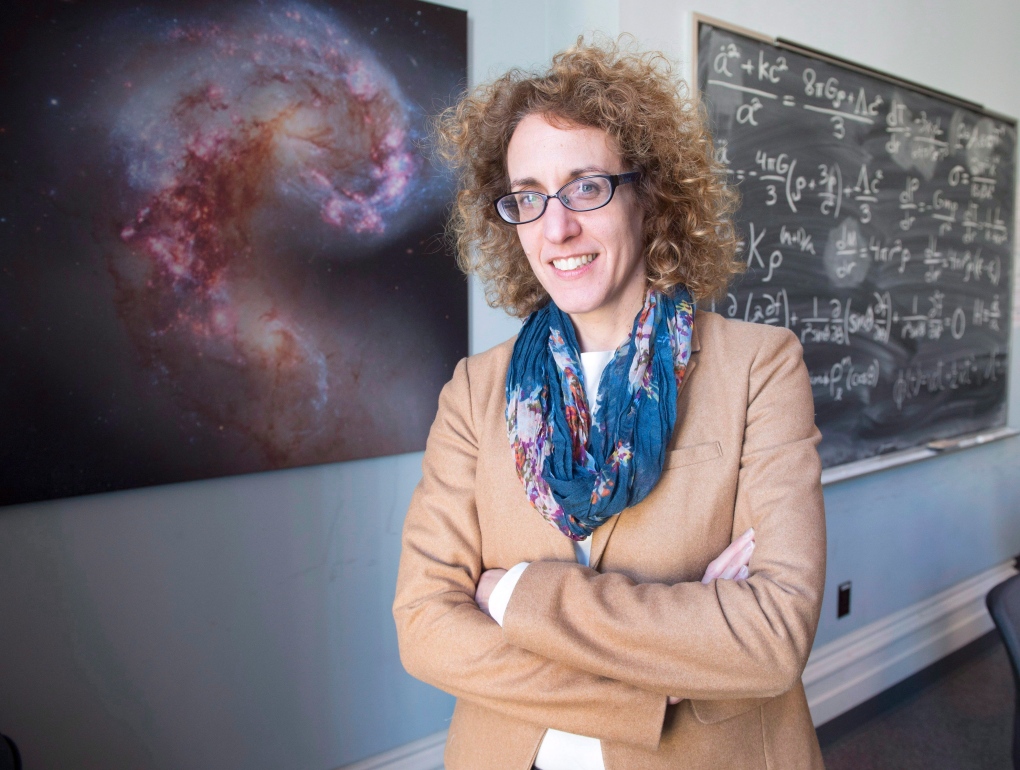

"It's one of the very rare-in-science 'Eureka!' moments," said Vicky Kaspi, director of the McGill Space Institute.

She said McGill PhD student Paul Scholz made the discovery last November during what was expected to be a routine data analysis project.

While sifting through data gathered from a radio telescope in Puerto Rico, Scholz saw one of the collected signals was particularly bright, as well as being consistent with another burst previously recorded from the same part of the sky.

"I got quite excited when I saw that and knew that it was a big step forward -- a big deal -- right away," he said.

As his colleagues gathered around his computer, Scholz found nine more repetitions, all from the same source.

Kaspi says the discovery is an important step toward discovering exactly what the bursts are and where they come from, with some big implications for humankind's understanding of the universe.

Astronomers know the bursts are quite common (occurring possibly thousands of times per day), travel vast cosmological distances and have a very powerful source.

But because they seemed to be one-time events, Kaspi said they were commonly believed to have been created by "cataclysmic events," such as exploding or colliding stars. However, such an event couldn't cause repeated bursts like the ones Scholz saw, she added.

Now, Kaspi and her fellow astronomers are excitedly considering new possibilities, such as the waves coming from a magnetar -- a highly magnetized neutron star.

The astrophysicist says there are some competing theories, including a study recently published in Nature magazine that seems to contradict their findings. It's also possible the pulses can be created by multiple kinds of sources, she said.

Since the bursts travel long distances between galaxies, figuring out what they are could teach researchers about how the universe evolved.

"It will help us understand how galaxies formed, what's in the vicinity of galaxies and what's in the material between them," she said. "We could learn a lot about the universe from these events... but we have a lot of work left to do."

Both Kaspi and Scholz hope a high-powered telescope called CHIME that is being built in Canada will be able to detect many more of the bursts and eventually lead scientists down the path to solving the mystery.

In the meantime, they'll keep watching the skies.