Iceland has the hottest showers in the world, and for good reason: on an island formed by volcanoes, partially covered by glacier ice and situated just below the Arctic Circle, a little hot water can mean the difference between misery and happiness – or between an icy wasteland and a green paradise.

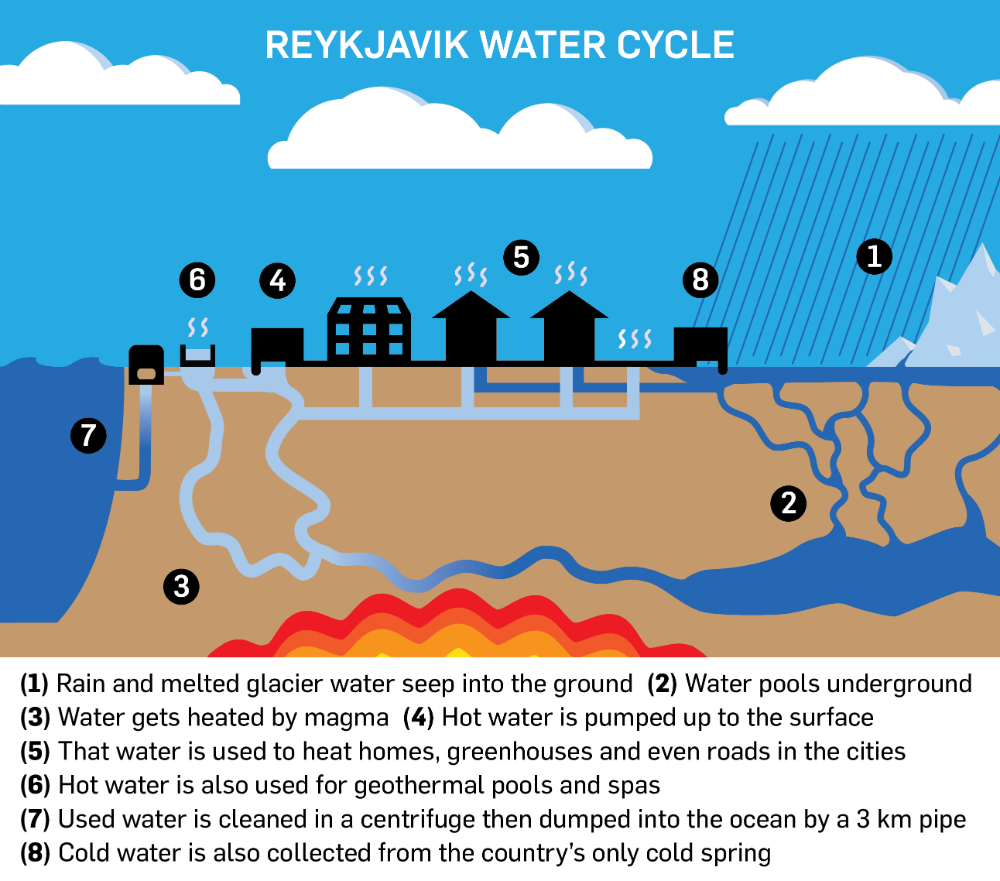

Icelanders have harnessed the power of their geothermal hot springs to transform their chilly northern country into a world leader in environmentally-friendly, sustainable energy. From engineering wonders like a hot water-driven heating system, to leisure activities like the famous Icelandic geothermal pools, Iceland is one of the most environmentally progressive countries in the world, thanks to the fire and water flowing beneath its surface.

The country of about 323,000 people is both reliant upon -- and at the mercy of -- its volcanoes. Those volcanoes sleep restlessly and wake frequently, reshaping the landscape with fresh lava flows and occasionally interrupting European air travel, as the Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption did in 2010.

But people in Iceland aren't afraid of the volcanoes. They're more concerned with the rapid melt of their glacier ice, which continues to retreat even as it helps drive Iceland's power generators. Icelanders have spent centuries studying the temperamental nature of their ice-bound volcanic island, and they've learned to harness its power to transform their country into an eco-friendly oasis in the middle of the north Atlantic Ocean.