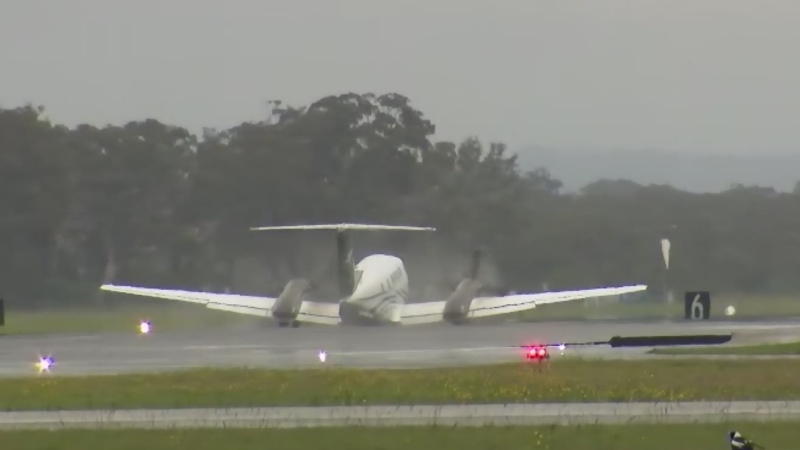

A tailings pond used to store toxic byproducts left over from mining released 10 billion litres of wastewater into lakes and rivers south of Prince George B.C.

Residents in the area have been under a water ban since Monday, while the province works to determine if the water is safe to drink.

CTVNews.ca looked at the use of tailing ponds in the extraction of natural resources and the environmental risk they pose.

What are tailings ponds?

Tailings ponds are used to store tailings – the byproducts left over from mining and extracting resources, such as oil, from the ground. Tailings include finely ground rock particles and chemicals used to extract the resource. The waste is mixed with water and stored in man-made lakes called tailing ponds.

As the tailings are stored, they undergo chemical reactions that could create even more byproducts.

What challenges do the ponds pose?

The ponds are typically very large and heavily impact the surrounding landscape. Canada's oilsands producers estimate that existing tailings ponds cover 176 squared-kilometres in northern Alberta. Tailings ponds typically account for 30 to 50 per cent of a mine's total footprint.

Once in the pond, the tailings sink to the bottom and the water from the top of the pond is recycled. It can take up to 30 years, however, for fine tailings and water to separate. And because the water has come into contact with chemicals, it's potentially toxic to fish.

The four-kilometre-long tailings pond from the Mount Polley Mine site held 10 million cubic metres of water and 4.5 million cubic metres of silt from the mining site, which following the breach made its way into Polley Lake and Quesnel Lake.

The area is B.C.’s largest salmon breeding grounds, and upstream from the Fraser River. The Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs has said the presence of heavy metals in the tailings could be devastating to salmon.

What are the environmental risks of the breach?

There's a risk of the tailings ponds releasing toxic chemicals into the environment, which is what happened at the Mount Polley Mine.

Earlier this year, a federal study confirmed that toxic chemicals from Alberta's oilsands tailings ponds are seeping into the Athabasca River. Earlier studies using models have estimated that seepage from a single pond could reach 6.5 million litres a day.

What are governments and industry doing to minimize the risks?

New rules to help manage the growing volumes of toxic tailings were introduced by Alberta's energy regulator in 2009. But according to the Pembina Institute, a Canadian non-profit think tank that's focused on clean energy, as of 2013 not a single company was complying with the rules.

While companies place an emphasis on reclaiming lands disturbed from mining and oil extraction, in the case of the oilsands only 0.2 per cent of the 176 squared-kilometres of land covered by tailings ponds is certified as reclaimed.