OTTAWA -- B.C.'s health minister is sounding less than enthused about flying to Ottawa for health care talks next week, suggesting there is nothing yet on the table that could break the stalemate over federal spending levels.

Terry Lake says he is not aware of any reason he should be boarding a plane on the taxpayer's dime in order to discuss health care, such as a change in the federal government's position.

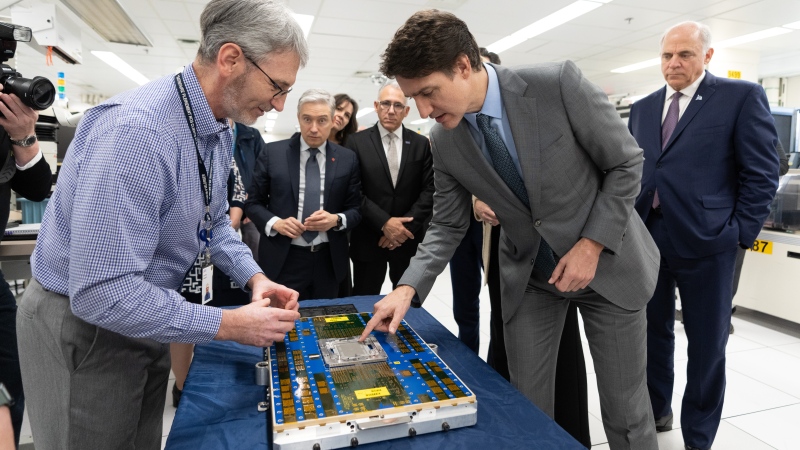

A funding formula feud is expected to dominate discussions with the finance ministers next week after the premiers made no progress on health in their talks Friday with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister refused to sign on to Trudeau's pan-Canadian climate change framework in the absence of an agreement on more federal money for health care.

The provinces are pushing back against a federal plan to cut in half the six per cent annual increase to health transfer payments next year.

Federal Health Minister Jane Philpott admits there is "still a lot of work to be done" before an agreement can be reached.

"The communications that we're having with the other ministers of health across the country is something that is a back-and-forth dialogue," Philpott said.

"It has to take place with all ministers of health at the table and obviously will be in discussion with my colleague, the minister of finance."

Lake said there's no point in further discussion if the federal pitch hasn't changed.

"We are rushing this," he said.

"I think the prudent thing to do -- if you want to have a serious, long-term health accord -- would be to roll over the six per cent for a year and have real, productive discussions about what a long-term health transfer ... looks like."

On Tuesday, Ontario proposed a new 10-year federal funding plan that would see Ottawa's health transfers to the provinces increase by 5.2 per cent a year.

Premier Kathleen Wynne called the idea a starting point for discussion and said, in exchange, the provinces would commit to spend the money on priority areas agreed on with Ottawa, such as mental health and home-care services.

A three-per-cent annual increase "is not going to cut it," Wynne said, especially when Ottawa provides only 23 per cent of the total amount spent on health care.

"There was a fair bit of consensus that (5.2 per cent) was the kind of increase that we need to look at."

Wynne said she is flexible on the length of an agreement but she would like to see 10 years to give provincial health systems the ability to plan for the long term.

The Conference Board of Canada and the parliamentary budget officer suggest 5.2 per cent is the actual rate of inflation on health care systems, said Lake, noting the mounting demands of the country's aging population.

"If we had some kind of idea that was on the table to discuss, it might be worth going (to Ottawa) but at this point we are still not hearing anything from the federal government in terms of what additional dollars might be," he said.

Some provinces have shown a willingness to accept a reduced annual increase in health transfers if, at the same time, the federal government agrees to put more money, over a longer period of time, into a health accord that targets improvements in home care, mental health services and innovation.

So far, the federal Liberals have promised $3 billion over four years for home care.

With files from Allison Jones in Toronto