TORONTO -- It's unacceptable that more than 1,200 cancer patients received diluted chemotherapy drugs and safeguards are needed to restore confidence in the health-care system, New Brunswick Premier David Alward said Monday.

"We need to make sure that we can give full confidence to the people of New Brunswick or Ontario -- or Canada ultimately -- that the proper system is in place, so that they can have full confidence in it," he told The Canadian Press.

"We have a very good system. But we can't afford, in any way, to take chances that it's not working the way it's supposed to."

Alward said he spoke to Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne about the cancer drug scare when he met with her Monday in Toronto.

"Are people concerned and are we concerned? Absolutely," he said after their meeting in her legislative office.

"That's why I'm very pleased to see how quickly the government of Ontario has moved forward with a decision on the investigation."

The governing Liberals have appointed a pharmacy expert, Jake Thiessen, to review the province's cancer drug system. A working group that includes doctors, Cancer Care Ontario, Health Canada and others are also looking at the issue.

A legislative committee also voted Monday to launch its own investigation into the drug scare immediately.

The committee will look into the apparent lack of oversight, standards and monitoring of companies like Marchese Hospital Solutions, which provided the diluted drugs.

It will also probe Ontario's pharmaceutical regulations and inspection procedures, and what impact the diluted drugs may have had on the patients, which included children.

Marchese, a Mississauga, Ont.-based company, was contracted to prepare the chemotherapy drugs for four hospitals in Ontario and one in New Brunswick, where about 186 patients received the weaker-than-prescribed drugs.

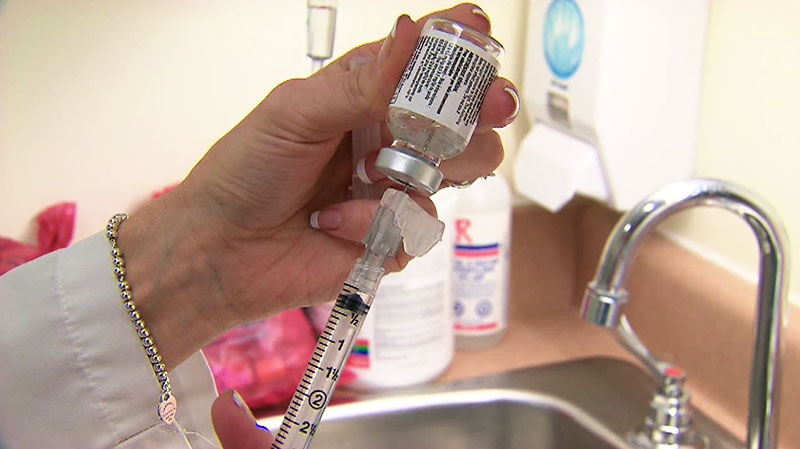

Too much saline was added to the bags containing cyclophosphamide and gemcitabine, in effect watering down the prescribed drug concentrations by up to 20 per cent. Some patients were given the drugs for up to a year.

But the diluted drugs didn't contribute to the deaths of at least 117 cancer patients at a London, Ont., hospital, said Ontario Health Minister Deb Matthews.

Neil Johnson, vice-president of cancer care at the hospital, said oncologists reviewed the cases and "they are confident that there is no causal link between the underdosing and the deaths," Matthews said in the legislature.

"He's saying it didn't contribute to their deaths," she added.

Ontario's New Democrats say they have their doubts.

"I'd like to see something definitive and researched-based," said NDP Leader Andrea Horwath.

Marchese said its products weren't defective, and suggested that the problem wasn't how the drugs were prepared but how they were administered at the hospitals.

But there is a gap in the oversight of companies like Marchese that mix drugs for hospitals, which usually do it themselves.

The company falls into a jurisdictional grey area, with the Ontario College of Pharmacists and Health Canada unable to agree on who was responsible for the facility.

The college oversees pharmacists, including those who may have worked independently for Marchese Hospital Solutions. Health Canada oversees drug manufacturing.

But Marchese wasn't considered a pharmacy or a drug manufacturer.

The need for clarity about who is responsible for what is an issue Health Canada has been dealing with for more than a decade.

A 2009 policy paper by Health Canada cited "a need to develop a Canada-wide consistency in approach to ensure that drug compounding and manufacturing are each regulated by the appropriate authorities."

Provincial authorities are responsible for compounding, where a drug and at least one other ingredient are mixed to create a final product in an appropriate form of dosing, the paper said.

Manufacturing includes producing or selling a product by a third party, it said.

The paper suggests that if there's a question about whether the activity is manufacturing or compounding, it should be raised with federal or provincial bodies, who can then determine who's responsible.

"In situations where the provincial/territorial regulatory authority decides that an activity does not fall within its jurisdiction, the activity is likely to be manufacturing and the parties involved must follow the federally regulated drug approval process for manufacturing drugs," it said.

The services provided by Marchese to hospitals appear to be something that has been traditionally done within a hospital pharmacy, which would fall under provincial supervision, said Health Canada spokeswoman Leslie Meerburg.

"This non-traditional business model takes a different approach," she said in an email.

"Between the federal and provincial-territorial governments, there are a variety of available regulatory tools. What we need to do is continue our work to understand this non-traditional way of doing business so that we can apply the right tools, at the right times, to protect patients."

In the meantime, the college is stepping in to provide oversight of new compounding facilities like Marchese.