TORONTO -- Keeping regular tabs on patients with a genetic disease that puts them at very high risk for developing multiple cancers over their lifetime has been shown to dramatically improve survival, researchers say.

The surveillance system, known as the Toronto Protocol, involves frequent testing of patients with Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a relatively rare condition caused by a mutated gene that is usually passed from one generation to another.

Patients with Li-Fraumeni are prone to developing a number of malignancies -- from leukemia and brain tumours to bone, muscle and breast cancer -- due to a mutation in a tumour-suppressor gene known as TP53.

However, a study of 89 patients published Friday in the journal Lancet Oncology found those who had regular testing to catch tumours early have a much better five-year survival rate -- almost 90 per cent compared to 60 per cent -- than those who did not take part in the surveillance program.

"What this shows is that in an albeit uncommon cancer-predisposition syndrome, it is possible using common clinical tools to detect cancers early and by so doing to intervene early and improve survival dramatically," said oncologist Dr. David Malkin, the director of the cancer genetics program at Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children, who headed the study.

"In the absence of a known cure or ability to prevent cancers from developing, this is really a major step in changing the natural course of the disease for these people."

Malkin said there are likely a few hundred families in Canada affected by Li-Fraumeni, which has a worldwide prevalence of less than one in every 5,000 people.

The lifetime risk of developing cancer is estimated at 73 per cent among male carriers and at least 93 per cent for female carriers. Most cases are inherited, but in about 20 per cent of those affected, there is no family history of the disease, meaning the defective gene on chromosome 17 arose spontaneously.

That's the case for 14-year-old Alaya Riley, who was told she had Li-Fraumeni two years ago after she developed a second kind of leukemia 10 years after the first. At three, she was diagnosed with a rare form of acute lymphoblastic leukemia that required aggressive treatment and a bone marrow transplant from her older brother Jayke.

But when Alaya was diagnosed at 12 with acute myeloid leukemia, calling for a second bone-marrow transplant from her brother, doctors decided to test her DNA and discovered she carried a mutated TP53 gene. Jayke, 18, does not have the defective gene.

"It was kind of relieving actually to know there was something (behind the cancers)," the Grade 10 student said Friday from her home in Cornwall, Ont.

"It was some type of explanation.... So it's not just being very unlucky," agreed her mother, Dinah Ener. "But of course there's a lot of implications."

Those implications include the development of other cancers.

While Alaya was being treated for her second leukemia, doctors detected suspicious nodules in her thyroid. The butterfly-shaped neck gland was surgically removed, but fortunately tests showed the nodules were benign, Ener said.

But last year, testing identified new tumours -- called osteosarcomas -- in some of Alaya's ribs on her left side. Three ribs were removed and her lungs were encased in a protective net.

In January, two more ribs were taken out after lesions were spotted during her scheduled imaging scans. They, too, turned out to be benign.

"It was really like bang, bang, bang," said Ener of the multiple cancer diagnoses. "So it's definitely been an eventful two years."

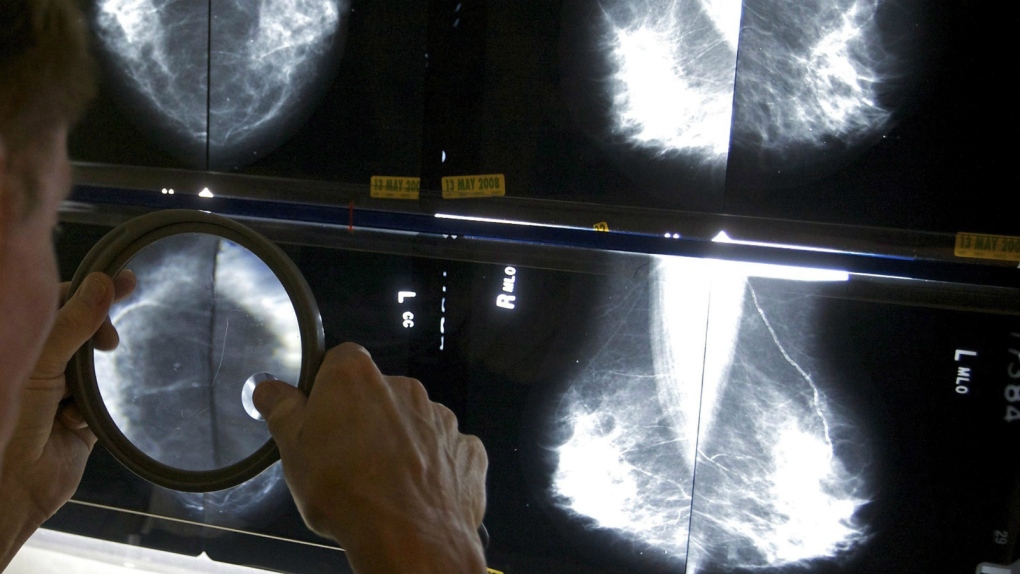

Malkin said the surveillance program for Li-Fraumeni patients, which was developed at Sick Kids Hospital in 2004 and has since been adopted around the world, involves regular cancer screening: blood tests every three months; ultrasound scans of the abdomen and pelvis every three to four months; and whole-body and brain-dedicated MRIs once a year.

As patients move into adulthood, annual colonoscopies and breast imaging are also added to the list, but starting many years earlier than those for the general population.

"It's a lot," conceded Malkin. "It's quite intense and when we talk with our families, both the adults and the kids, they do definitely comment on that."

While the cancer-screening schedule can be time-consuming -- Alaya's family must drive her to Sick Kids in Toronto and the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) in Ottawa for different tests, with long waits once there -- Ener said it's reassuring to know her daughter is being closely monitored.

Earlier this week, the teen was in Toronto and next week she has five tests scheduled at CHEO, but Alaya appears to take it all in stride.

"Most people would feel like a lab rat or something like that, but I don't feel that way," she said. "I believe that everything they do is for precaution."