When the Ontario government banned OxyContin four years ago, the goal was to curb rampant abuse of the powerful painkiller.

But doctors in London, Ont., are now seeing people abuse the drug’s “tamper-proof” replacement – with gruesome consequences.

OxyContin -- a brand name for a painkiller called oxycodone – was removed from sale in 2012.

The use of a related painkiller, Hydromorph Contin, exploded after that - a formulation designed to thwart people from dissolving the pill and injecting it, it is designed to turn into a thick, gel-like substance when exposed to water.

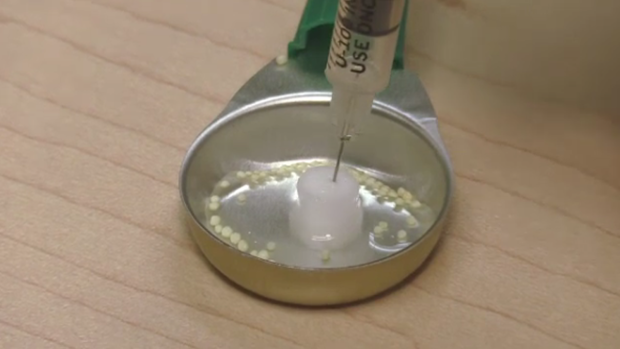

A filter is used to draw the drug into a syringe.

But desperate ingenuity has led to some addicts finding a way to draw the drug into a syringe using a filter – a method that can cause significant heart damage, says one family medicine specialist.

“What we actually did was create a new problem,” says Sharon Koivu, a doctor in the family medicine department at London Health Sciences Centre. “In some ways, maybe even a more serious problem.”

When crushed and injected, fragments of the pill sometimes end up in the mixture. These shards can travel through the blood into the heart, scratching the organ’s interior and damaging valves.

The result, says cardiac surgeon Michael Chu, is an increase in strokes, blood clots and death among addicts. Chu specializes in repairing damaged valves at London Health Sciences Centre.

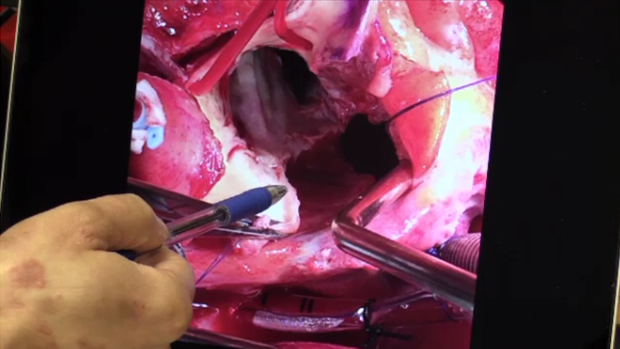

“Surgeons should shudder if they ever see this,” Chu says, pointing to a picture of a damaged heart.

“This is a hole into the left side of the heart. Basically the entire middle of the heart’s been cut out here because of infection,” he says.

Cardiac surgeon Michael Chu points out the damage caused by a drug-induced heart infection.

Doctors in London aren’t sure how large a problem they’re facing because deaths from drug-induced heart infections aren’t counted provincially like deaths from drug abuse are.

But what used to be one to two consultations of this kind a month has become three to four per week, Chu says.

“It’s been a very dramatic increase and rise, almost of epidemic proportions.”

In some cases, heart valves can be surgically rebuilt, though the procedure is challenging and time-consuming. And while infections can be treated, getting addicts to follow through with an antibiotics regimen can sometimes prove challenging, doctors say.

Koivu says before working at London Health Sciences Centre she’d never seen this sort of heart valve inflammation and infection. She also says the majority of her patients are in their 20s and 30s.

“When I’m watching so many young people who are so ill and dying of something that truly is preventable, it's very concerning,” Koivu says. “And we need to be having an urgent response to this urgent problem.”

With a report from CTV’s medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip