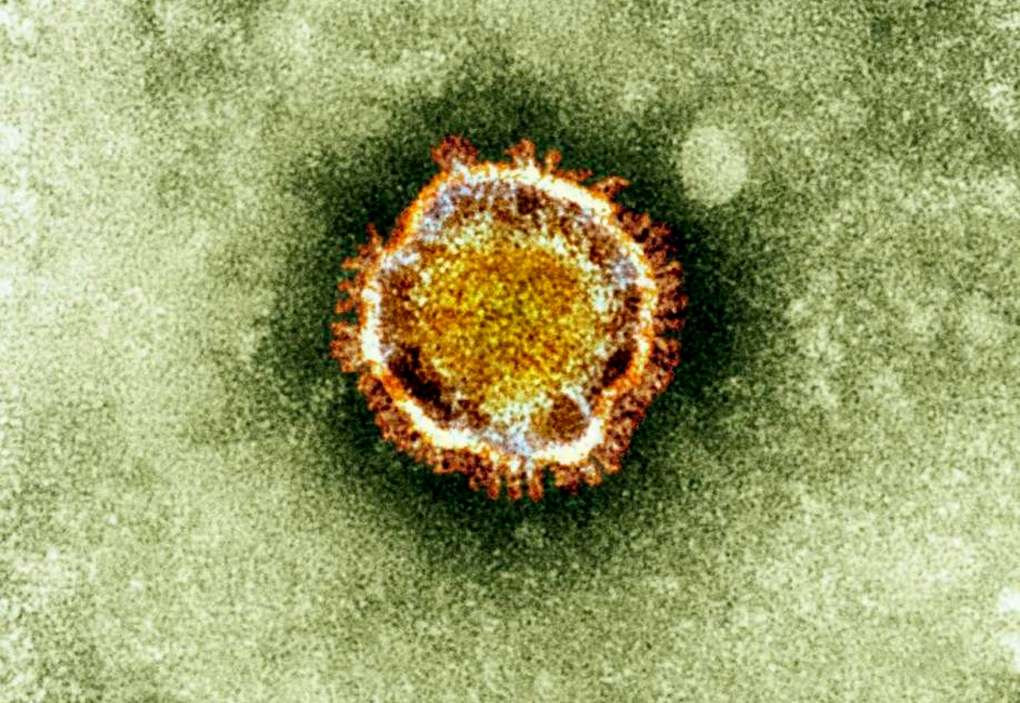

In the world's eyes, Saudi Arabia appears to be ground zero for the new MERS coronavirus, with the country accounting for nearly 80 per cent of known cases. But the kingdom's deputy minister of health believes this virus is infecting people around the world, and other countries aren't catching cases because they aren't looking.

In a wide-ranging interview, Dr. Ziad Memish also said that while he takes the new virus seriously, he doesn't believe the outbreak deserves the type of attention it is receiving. Earlier this week, the director general of the World Health Organization, Dr. Margaret Chan, called the new coronavirus "a threat to the entire world."

"We're spending a lot of money, we're making a lot of investments trying to see what this disease is about and where it's coming from and how we can manage it," said Memish, who received his medical training in Canada.

"But ... you know, the H7N9 killed 35 people and there were 134 odd cases in a few weeks. So I think, yes, it's a concern, but not as big a concern as is being portrayed in the media."

(The latest WHO figures for H7N9 are 132 cases and 37 deaths.)

Memish noted that four million Muslims from around the world have travelled to Saudi Arabia already this year to perform a pilgrimage known as Umrah. "We have not seen anything disastrous to date and, knock on wood, I hope nothing will happen."

Umrah is secondary to the better known annual Hajj. It can be performed at any time of the year, according to the Saudi Ministry of Hajj, though when Muslims make this pilgrimage during Ramadan, the month of fasting, it is considered equal to doing the Hajj.

This year Ramadan begins July 9 and public health experts are already worrying about whether the influx of pilgrims will lead to spreading MERS around the globe.

Last week at the World Health Assembly -- the annual meeting of WHO member states -- Chan and others lavished praise on China for the active and transparent way in which it has been trying to trace and contain the H7N9 bird flu outbreak that exploded there earlier this spring.

In sharp contrast, Saudi officials were repeatedly pressured throughout the weeklong meeting for more information about the country's ongoing MERS outbreak and what it is doing to try to find the source of the infection.

To date there have been 50 confirmed infections with the Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus, 27 of them fatal. Saudi Arabia has recorded 39 of those cases and 18 of the deaths. (Saudi officials say they have had 38 cases, but the WHO counts a man from Britain who was infected in Saudi Arabia as a Saudi case.)

Prior to early May, there had only been 17 confirmed cases from five countries: Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and Britain. (A cluster of three cases in Britain was triggered by the man who became infected while travelling in Saudi Arabia.)

But Memish announced 13 new cases in quick succession. The cases were linked to a hospital in al-Ahsa in the eastern part of the country and human-to-human spread is suspected in at least some of the cases.

Since early May, Saudi Arabia has announced a total of 28 infections, at least a dozen of which have been fatal. As well, two cases were reported in Tunisia, the children of a man who died of what was probably MERS. The man became ill while travelling in Saudi Arabia.

Saudi officials have offered few details on these new infections. Memish revealed there may have been spread in a second hospital, also in Saudi's Eastern Province. But reports from the region suggest several hospitals have had or are still battling outbreaks.

Despite the complaints about the kingdom's lack of transparency, Memish insisted he has been forthcoming.

"People say we're not transparent. People say we're not giving information. But as we spoke to the DG" -- the director general -- "and WHO we said everything that we are learning," Memish said.

He clearly chafes at the suggestion that the virus is coming from his country, or region.

In fact, in an article Memish published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine, he said an earlier iteration of the WHO's advice for how to find cases probably led to an underestimation of the scope of the problem, because it linked infections only to countries on and around the Arabian Peninsula. The most recent version of the guidance talks about the Middle East.

"If you ask why we're picking up more cases in Saudi recently, it's because we're just looking harder and harder. We're processing hundreds of samples a day from different parts of the country. So far we sampled 1,500 or 1,700 samples in the whole of Saudi," he said.

"I don't think any country in this world is doing that much testing. And I guess the more you look the more you'll find."

If other countries -- even countries outside the Middle East -- conducted similar testing, they too would find MERS cases, he said. "I would not be surprised if it's in every other country in the globe."

He supported that argument with the fact that in many cases of pneumonia, the bacterial or viral cause is never found. Still, Memish's suggestion that those could be undetected MERS cases met with skepticism from infectious diseases experts.

"To suggest that cases of MERS-CoV" -- CoV stands for coronavirus -- "infections are being missed all over the world carries no epidemiologic or virologic credibility among those of us who have spent our careers tracking down global emerging infections," said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Diseases Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

"Such a statement merely blames the rest of the world for the continued problems with transparency by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in responding to this public health crisis."

Osterholm said if undiagnosed MERS cases were in hospitals in other parts of the world, health-care workers would be contracting the disease as they did SARS in 2003. (MERS is from the same virus family as the SARS coronavirus.) "They would become the sentinel canaries. We're not seeing those."

Gregory Hartl, a spokesperson for the WHO, said if there were clusters of MERS cases elsewhere, they would be garnering attention, testing or no testing. "The outbreaks that we're seeing now would not likely be overlooked even if a country weren't looking very hard."

As well, he noted that some countries have been testing stored blood samples looking for evidence of antibodies to the virus, a finding that would suggest people in those countries had been exposed to MERS in the past. So far there have been no positive findings, he said.

One of the issues that has plagued efforts to find cases, particularly previous cases that were undiagnosed at the time of the infection, is the lack of validated MERS blood tests.

Several laboratories in Europe have developed tests. But in order to be certain that a test is working -- that it is picking up true positive cases and is not generating false positives -- developers need to test it on blood from people who have survived the infection. The only country with significant numbers of MERS survivors at this point is Saudi Arabia, which has reportedly not responded to requests from some European academic labs that have developed MERS blood tests.

Asked about that, Memish said Saudi Arabia is collaborating on the development of MERS blood tests. He said the country is working with scientists at Columbia University in New York, and with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

"We're working with CDC. We're just trying to finalize the agreement," he said.