Ontario researchers used an Alfred Hitchcock show to detect brain activity in a patient who had been unresponsive for more than a decade. The researchers say their study raises questions about the techniques used to diagnose a patient as being “unconscious.”

The brain-injured patient, who has been behaviourally unresponsive for 16 years, was able to monitor and analyze information in a way that was previously thought to be not possible, the researchers said.

The results of the Western University study were published Monday in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA.

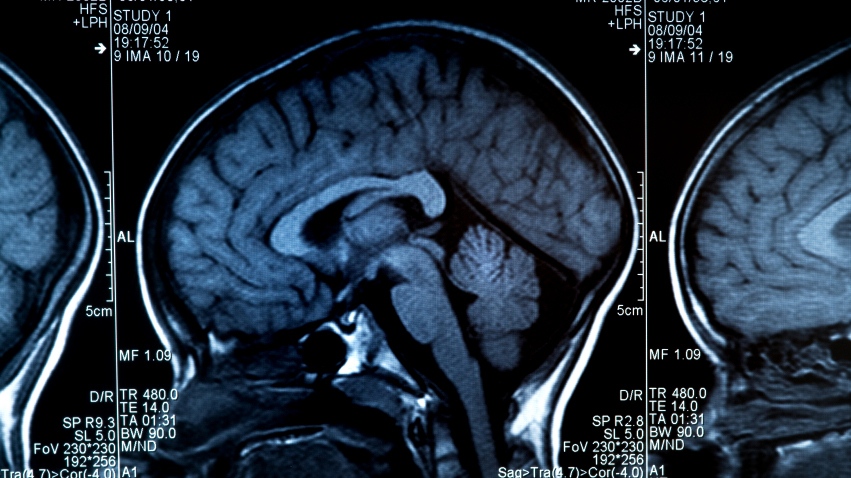

During the study, researchers at Western University showed three groups of healthy participants (66 in total) and two unresponsive patients a "highly engaging" episode from "Alfred Hitchcock Presents" while they lay inside an MRI scanner.

The episode was "Bang! You're Dead."

As the episode played, the MRI scanner tracked the participants' brain activity and found a similar pattern common to all the healthy participants.

A similar pattern was also observed in one of the unresponsive patients. The 35-year-old patient had been behaviourally unresponsive since suffering a severe brain injury when he was 18 years old, the researchers said.

The results of the study showed that the unresponsive patient was not only consciously aware, but that he also understood the movie.

"The patient's brain response to the movie suggested that his conscious experience was highly similar to that of each and every healthy participant, including his moment-to-moment perception of the movie content, as well as his executive engagement with its plot," the study said.

Lorina Naci, a postdoctoral fellow and the study's lead researcher, said that this was particularly striking because this patient hadn’t been able to demonstrate any behavioural responses during previous clinical assessments.

In order to determine a patient's level of consciousness, doctors typically test patients to see how they respond to various commands or orders.

"At no point had this patient in his entire history been able to perform any of these commands, so he was deemed to be in a vegetative state," Naci told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview.

The patient had also previously failed to show any signs of sound or visual recognition or interaction with objects or people in his environment, including his family members.

A new technique?

Naci said the results of the study suggest that there may be other ways to diagnose a patient as being unconscious.

"For the first time, we show that a patient with unknown levels of consciousness can monitor and analyze information from their environment, in the same way as healthy individuals," she said in a statement.

"We already know that up to one in five of these patients are misdiagnosed as being unconscious and this new technique may reveal that that number is even higher."

Naci said that the next step for the research group is to test a larger number of nonresponsive patients, to see how often this phenomenon might occur. The group would also like to determine what types of brain-injured patients are most likely to experience a similar result.

"What we know from brain-injured patients is that in terms of consciousness they're a very heterogeneous group," she said.

Dr. Adrian Owen, another of the study's authors, said the group's approach to diagnosing consciousness raises important questions about the way we care for unresponsive patients.

"This approach can detect not only whether a patient is conscious, but also what that patient might be thinking," he said in the statement.

Naci agrees, noting that the study results can have practical implications for the care of patients who are in a vegetative state.

"We should be very mindful and concerned in the way that we treat them, and also expose them to more and more life experiences, and cultural experiences (like a movie)," she said, adding that the goal is to "provide them with a more nurturing environment."

She said she'd also like to see unresponsive patients eventually have more control over their own care.

"For the first time, we understand that patients in this condition can have a very coherent mental life," she said, noting that most decisions for unresponsive patients are currently made by their families or by medical staff.

"What we hope to see in the future, is to put back in their hands some of the autonomy that has been lost in their injury."