Medical experts are accusing two Canadian-researched studies of dangerously confusing the public health conversation around sodium, after the studies used questionable science to conclude a low-sodium diet might be dangerous.

The two studies say consuming too little sodium may be harmful, putting people at risk of heart attacks and strokes. They also conclude that consuming more potassium-rich foods can offset the potential cardiovascular issues linked to a high-sodium diet. The studies, which rely on data from McMaster University’s Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology (PURE) research project, were published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine. Their conclusions run counter to a third study published in the same journal issue, which supports the more commonly-supported view linking a high-sodium diet to a number of cardiovascular diseases.

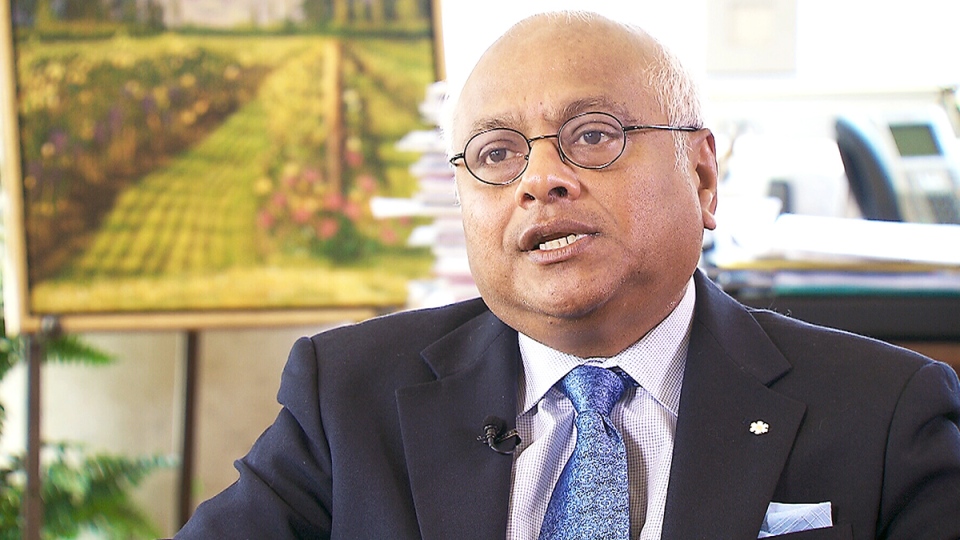

The PURE studies suggest global efforts to cut people’s sodium intake may actually be harmful, and could lead to increased risk of heart attack, as well as low blood pressure. “The right level of sodium is not zero. You need a certain amount for the cells to function, and for the body to function,” said Dr. Salim Yusuf, lead author of one of the PURE studies and a cardiologist and epidemiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. Lower sodium reduces blood pressure and can harm the kidneys and also cause heart attacks and strokes, he said. Sodium is a key chemical component in salt, but large amounts of it can also be found in processed and fast foods.

Yusuf recommends a sodium intake of between three and six grams a day – well above the World Health Organization’s recommended maximum dose of two grams per day. “Below that is harmful, and above that is harmful,” said Yusuf, whose study included data from 100,000 people in 17 different countries. “There is a sweet spot, and you have to hit the sweet spot.”

The two pro-sodium papers were published alongside a third study, which took a decidedly different take, analyzing the deadly long-term effects of high-sodium intake on people around the world.

The third study published in the journal says more than 1.6 million cardiovascular-related deaths can be attributed to excess sodium per year. It analyzed data from three-quarters of the world’s countries and found that people were consuming almost double their maximum recommended daily sodium intake, producing a heavy burden for the world’s health-care facilities.

The study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and conducted by a team of more than 100 scientists, under the auspices of the WHO. The study found the average worldwide sodium consumption rate is 3.95 grams, almost twice the amount recommended by the WHO.

The study acknowledges that it does not take into account the full impact of sodium around the world, as it focused only on deaths attributed to high-sodium diets. Sodium has been tied to a number of non-fatal health issues, including hypertension, osteoporosis, obesity and stomach cancer.

Dr. Norm Campbell, a leading cardiovascular researcher at the University of Calgary, said the third study is sound, and the two pro-sodium articles should not change the conversation around sodium. He said they rely on non-recommended research methods, and science will likely reject the studies once they’ve been properly reviewed. “Controversy sells,” Campbell told CTV News on Wednesday. “It delays necessary public-health efforts, and endangers the lives, probably, of millions of people globally,” he said.

The advocacy organization Center for Science in the Public Interest also slammed the PURE studies on Wednesday, saying they should not change the minds of health authorities. “The PURE studies suffer from serious shortcomings,” the CSPI said in a statement on Wednesday.

The PURE study results run counter to accepted Health Canada guidelines, which recommend adults consume 1.5 grams of sodium a day. Hypertension Canada says up to two grams a day is the limit.

The PURE papers argue those current sodium recommendations should be revised.

“If you were to lower sodium to what current guidelines recommend, you might be putting yourself at increased harm,” said Dr. Andrew Mente, a researcher at McMaster involved with one of the PURE studies. “Perhaps it’s time to look at revising the guidelines and getting more data from randomized controlled trials,” he said.

The PURE studies also found that potassium, which is found in vegetables and fruits, mutes the effects of sodium and can lower blood pressure and the risk of cardiovascular disease.

The research is igniting a salt war, with some scientists saying the new research is flawed and sending the wrong message.

Campbell said the PURE studies used sodium measurements from a single urine test which are not valid measurements for salt exposure. He also said the PURE studies are attempting to downplay the dangers of a high-sodium diet.

“We do know that commercial interests interfere with science,” he said. He cited past instances of the tobacco industry supporting pro-cigarette papers to soften public opinion. “We’re seeing the same thing now,” he said.

“I think they’re going to confuse an awful lot of people,” Campbell said. He recommends Canadians continue to strive for a low-sodium diet.

With a report by CTV News' Medical Specialist Avis Favaro and Senior Producer Elizabeth St. Philip