TORONTO -- Canadians sickened by tainted beef from XL Foods should be tested annually over the next few years for lingering health problems that can be caused by E. coli, says a researcher who studied the long-term effects of infection in residents of Walkerton, Ont.

In 2000, the municipal water supply in Walkerton was contaminated with E. coli 0157:H7, the same toxin-producing strain that has led to the massive recall of beef from Alberta's XL plant and has so far sickened 11 Canadians in four provinces.

In the water-borne outbreak more than a decade ago, 2,300 residents developed an E. coli infection and seven of them died, including one child. Twenty-eight of those stricken developed hemolytic uremic syndrome, or HUS, which occurs when a toxin from the bacteria damages blood vessels, leading to kidney failure, gastrointestinal complications and neurological effects.

A series of followup studies of affected residents found an increased risk of high blood pressure as well as related kidney damage and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. William Clark, a kidney specialist at Western University who led those studies, said he expects individuals who became ill from the contaminated beef in recent weeks would also be at risk of such long-term health problems.

"And probably they need to be followed up on an annual basis for the first two or three years to determine if they have developed any of these abnormalities, which can actually be treated," Clark said Tuesday from London, Ont.

"But the important thing is they need to be followed up and assessed. They need to have some simple screening tests in terms of their kidney function."

Clark said the research showed that those infected with Escherichia coli 0157:H7 had a 33 per cent increased risk of elevated blood pressure, which can cause both kidney damage and the cardiovascular disease that can lead to heart attack and stroke.

E. coli 0157:H7 is just one of numerous strains of the organism, most of which live harmlessly -- and even helpfully -- in the intestinal tracts of all mammals, including humans, said Dr. Dick Zoutman, a medical microbiologist and infectious disease specialist at Queen's University.

But 0157:H7 and related strains produce the "shiga" toxin, which can inflame the intestinal tract, swarm into the blood and travel to the kidneys, where it can severely damage cells. Symptoms can include watery to bloody diarrhea, intestinal cramping or tenderness, and nausea and vomiting in some people.

The most severe complication is hemolytic uremic syndrome, which causes kidney failure and can be fatal.

Young children, the elderly and people with compromised immune systems are at risk for developing more serious disease from an E. coli infection, Zoutman said.

"The majority of patients who ingest this E. coli 0157 might get a mild diarrheal illness that most of would write off as mild gastroenteritis," he said from Kingston, Ont.

Some people get a more severe form of the illness, marked by bloody diarrhea that would likely send them to their doctors, while others would develop full-blown hemolytic uremic syndrome that requires hospitalization, he said.

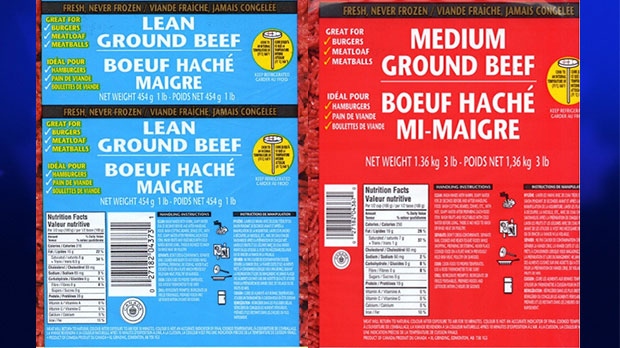

With the extent of the recall -- more than 1,800 products have been recalled in Canada alone -- one would think the number of reported cases of illness across the country would be higher than 11.

But Zoutman said those cases may be only the tip of the iceberg.

"This was such a massive recall that it will take time ... because people would not have appreciated the fact that they have that product in their refrigerator and in their freezer and then consume it," he said.

"So there's quite likely to be product persisting in the community that can cause disease for some time, until we're convinced that (all the) product has been recalled."

Dr. Donald Low, microbiologist-in-chief at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, said it's puzzling why there haven't been more reported cases, given the extent of the recall. The affected beef products were sold in numerous outlets across the country and exported to more than 20 countries.

Some people could develop diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, and assume they had picked up some garden-variety intestinal bug, not connecting the symptoms to having eaten beef that might have been contaminated with E. coli, he suggested.

That scenario fits with the incubation period for E. coli 0157:H7 infection, which can last two to 10 days before symptoms appear, with a median period of three to four days.

But Low said that as the public becomes more aware of the E. coli outbreak, they may seek medical care for episodes of diarrhea -- especially bloody diarrhea. That allows health-care providers to confirm the diagnosis and report any cases to public health authorities.

Timing may also be a factor, he said. During the summer months, food-borne illnesses tend to be more common because many people prepare meat on outside grills, yet may fail to cook it enough to kill the various types of bacteria that can cause illness, including E. coli.

With the arrival of fall, cooking methods may have changed, lowering the risk of food-related infections from undercooked meat.

"It may well be because of the time of year," he said. "We're getting out of the barbecue season."