A Canadian invention designed to improve blood flow to the legs has caught the eye of researchers who think it could play a role in preventing the hundreds of leg amputations from diabetes that happen ever year in Canada.

It's called the Venowave, a battery powered device strapped to the calf that squeezes the leg and massages blood upward, to improve circulation.

Researchers at McMaster University are intrigued by the device. They've done one study showing the device helps cut leg swelling from vascular insufficiency. Another study showed it helps prevent deep vein thrombosis, or blood clots that form in veins inside the leg.

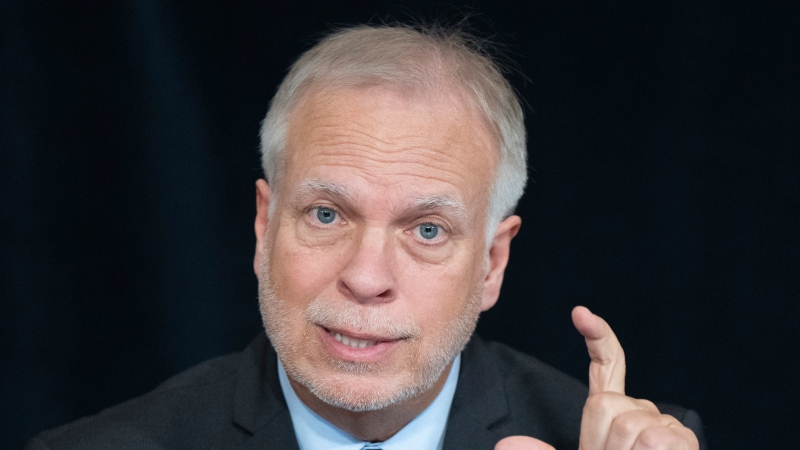

Dr. Sonia Anand, an associate professor of Medicine at McMaster, says the simple device offers a new way of treating vascular diseases.

"It is definitely exciting to have a potential new option to treat patients with peripheral arterial disease, because we don't have that many options," she says.

But some think the device may have another big potential use: treating leg wounds in people with diabetes.

About 60 to 70 percent of people with diabetes develop some form of nerve damage, or neuropathy, which can cause a loss of feeling in the feet and legs.

The loss of sensation and poor circulation can combine to make diabetics less able to fight infection and to heal simple foot wounds. Too often, those simple foot infections eventually result in amputations.

Now, doctors treating diabetics using the Venowave have noticed that the leg wounds of their patients are healing much faster.

Eighty-year-old Ferguson Kewley watched his diabetic foot sore quickly heal while using the device.

"The wound was on the side of the small baby toe and it was open and it was not healing. And the doctor explained to me if you don't heal you are going to lose your foot, explains Ferguson.

But after wearing the Venowave for three weeks he noticed a dramatic change.

Ferguson said it is a miracle. "I would not have believed it if I had not seen it," he says. Even his doctor was surprised.

Now researchers want to investigate the device's usefulness among diabetics.

"Certainly, it is something that should be tested because patients with diabetic ulcers don't have any options at all," says Dr. Anand.

But such a study would cost over $1 million – and doctors admit it would be difficult to get funding from government agencies to test a commercial product, even though it may have cost savings to the health-care system.

"In terms of wound healing we would require two to 300 hundred patients with diabetic ulcers. Half would get (the device), half would not and we would measure time to healing," Anand says.

But the million-dollar study would be a heavy investment, according to inventor John Saringer, the head of Saringer Life Sciences. Without support from either a funding agency, or someone who can finance a study of the device, its potential may never be fully confirmed.

"My greatest fear is that I will not be able to finance the company long enough to see financial success," he says.

Saringer says his company is now taking an unusual step. He's temporarily offering the device for free to diabetics whose doctors send in a request. In return, he is asking for testimonials in the hopes that positive feedback will generate enough support for a study.

"We have offered our product on a trial basis to anybody who feels that they can benefit from it," Saringer says.

With a report from CTV medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip