Even young football players who endure repeated concussions could be at risk of developing chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, say doctors who have found the brain disease in a former player who died at age 25.

Several former football and hockey players have been diagnosed in recent years with CTE, a brain disease that can only be confirmed after death and that is linked to depression and progressive dementia.

In many of these cases, the players didn’t start showing symptoms until years after their sports careers were over. But doctors with the Boston University School of Medicine say they have found the disease in a player who died only a few years after quitting football.

They describe the man’s case in a new report in JAMA Neurology. The young man, they write, played football for 16 years, starting when he was just six years old. Over the years, he experienced at least 10 concussions, including his first at eight years old.

He continued to play as a defensive linebacker in college, but in his freshman year, he experienced a serious concussion that resulted in a momentary loss of consciousness. He later developed many classic post-concussion symptoms including headaches, neck pain, difficulty with memory and concentration.

The symptoms persisted and eventually forced him to stop playing football. By his junior year, the man was failing his classes and dropped out of college.

He developed the signs of depression including apathy, loss of appetite, and feelings of worthlessness. He had difficulty maintaining a job and began using marijuana to help headaches and anxiety and to help him sleep.

By the time he was 23, his wife reported that he had also become verbally and physically abusive toward her, which she said was unusual for him

Suspecting that something was wrong with his brain, the man agreed to undergo several cognitive tests and asked that his brain be donated to researchers .

After he died of an unrelated heart infection, Dr. Ann McKee and Dr. Jesse Mez of Boston University School of Medicine conducted an autopsy and were allowed to review his medical records and interview his family members.

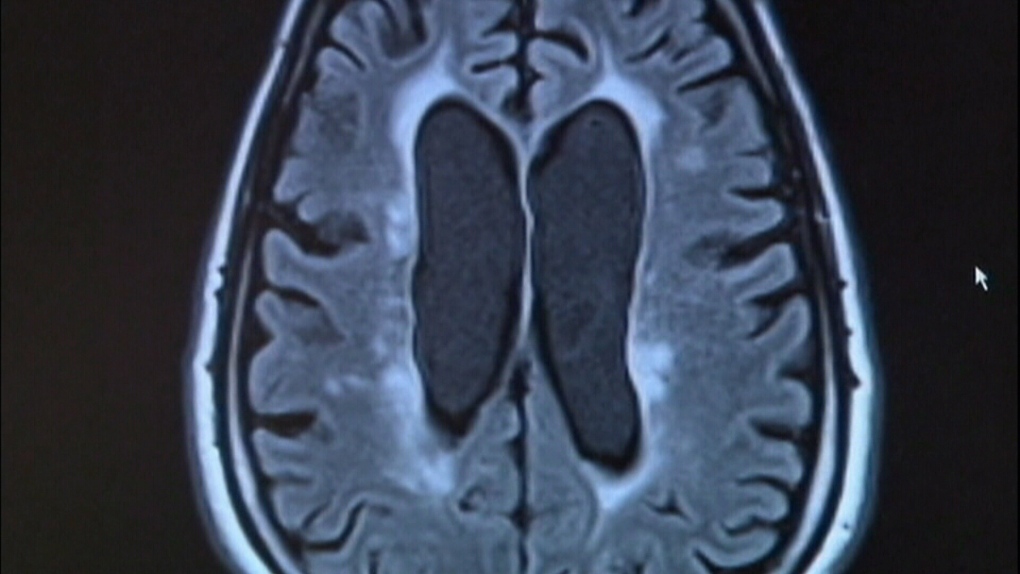

The researchers write that the man’s brain contained the telltale signs of CTE, including a buildup of tau protein, which accumulates in Alzheimer’s patients.

But they also note the man had post-concussive syndrome and a family history of addiction and depression, so it is not possible to say that CTE was his primary diagnosis.

In an accompanying editorial, Columbia University neurologist Dr. James Noble writes that it is becoming apparent that CTE can affect even young athletes involved in contact sports.

“What distinguishes this case from other similar cases was his inclusion in the Understanding Neurologic Injury and Traumatic Encephalopathy (UNITE) study, with an evaluation that uniquely included neuropsychological testing within months of his young death,” he writes.

But he adds that this case still leaves many questions about CTE and concussion unanswered, such as how many and what kind of concussions are most dangerous to the brain. It’s also not clear why some people are able to recover from concussions, while others develop long-lasting symptoms, as this young man did.