Society shouldn’t be spending resources to diagnose children as dyslexic -- an imprecise term that has become “meaningless,” researchers argue in a new book titled “The Dyslexia Debate.”

“This term is really flawed,” said author Julian Elliot, a professor of education at Durham University. “It’s really difficult to actually pin down what people mean by it.”

Elliott, who began his career as a teacher for children with learning difficulties, says that five to ten per cent of the population is diagnosed by educators, clinicians and researchers with dyslexia for a myriad of reasons, including:

- people who have difficulty with decoding single words,

- those who score at the low end on reading tests; and

- those who show a discrepancy between reading performance and IQ.

But oftentimes, symptoms found in one person can be absent in another person diagnosed as dyslexic, which is why the term lacks “scientific rigour and educational value,” Elliott says.

“I think we should discontinue the use of the term dyslexia and try to have a system that identifies the needs of all children who struggle to learn,” the author said.

Elliott says the focus should be shifted toward identifying children as young as four or five years old who have problems with reading comprehension, spelling, and intellectual functioning, rather than waiting to diagnose them later on in life.

The author says teachers should also begin building individual profiles of students in order to pursue the best form of treatment.

“A child who can’t read very well who is super bright would need a very different approach to their general education than a child who can’t read very well, and perhaps finds the most basic ideas very difficult to grasp,” Elliott said.

By abandoning the term dyslexia, Elliott says schools will be more likely to identify all children with learning disabilities who would benefit from additional resources.

And Elliott suggests replacing the term dyslexia with “reading disabled” to refer solely to children who struggle to decode text.

By doing so, educators will be able to build individual profiles of children based on their reading abilities, rather than “using a single word to try and encapsulate everything,” Elliott said.

Diagnosis can help

But Dr. Maureen Lovett, a neuroscientist at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, says that early intervention can in fact prevent children from developing learning disabilities.

She says that dyslexia isn’t too broad of a term, and that diagnosing a child can be beneficial. “The point of the diagnosis or label is so that you know what the child needs in terms of their education,” she told CTVNews.ca.

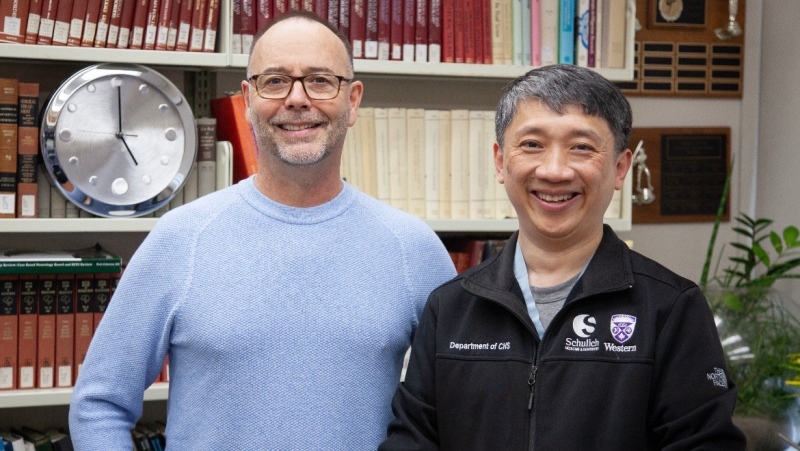

Elliott worked alongside his colleague and co-author, Dr. Elena Grigorenko of the Yale School of Medicine for five years, researching education, genetics, neuroscience and psychology. The book is set to be published on Mar. 1.