VANCOUVER - Canadian researchers have developed a predictive model for detecting lung cancer in early stages when the disease has a greater potential to be curable.

The Pan Can Model, developed by a team of health researchers across the country, uses a wider range of factors that contributes to lung cancer compared with current screening practices. The new study found the model resulted in more people being diagnosed with the disease at early stages.

Dr. Stephen Lam, the Vancouver-based co-principal investigator on the study, said although smoking rates have dropped significantly, past smokers are still at risk of developing lung cancer and survival rates for the disease are poor.

"The overall survival of lung cancer patients is less than 18 per cent," said Lam, who is also chair of the Provincial Lung Tumour Group at the BC Cancer Agency. "If we find cancer early, the survival is over 70, 80 per cent range so that is why this is a dramatic change in how we find and treat cancer."

The study looked at more than 2,500 current and former smokers between the ages of 50 and 75 in eight cities across Canada who were determined to have minimum two per cent risk of developing lung cancer within six years.

Factors that determined their risk included age, how long and how much they smoked, family history of lung cancer, education level, body-mass index, recent chest X-ray results and history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

These factors differ from the leading U.S. study on the issue, the National Lung Screening Trial, which focused specifically on participants' age and smoking history.

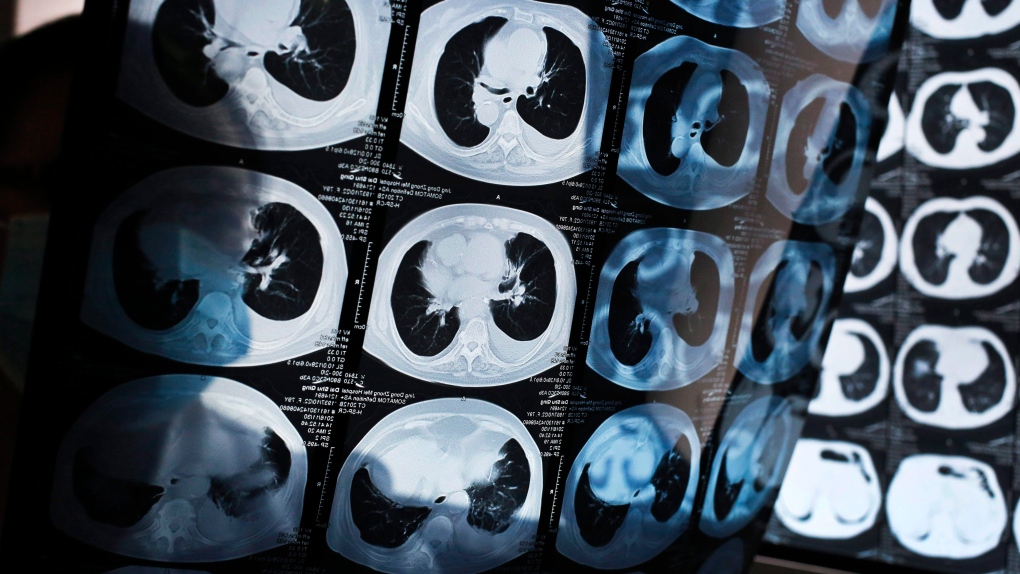

Canadian participants were tested with a low-dose CT scan at the onset of the study, and then at the one- and four-year mark.

Lam said the radiation exposure from the low-dose CT scan is small enough not to cause any harm and is extremely effective in catching lesions even one millimetre in size that X-rays and other testing could miss.

The screenings resulted in 6.5 per cent of participants being diagnosed with lung cancer - a higher rate than the four per cent of cases caught through the U.S. model.

Seventy-seven per cent of the Canadian diagnosed were also caught in very early stages, compared with 57 per cent of cases in the U.S. trial.

Ottawa resident Debi Lascelle, 60, was among those diagnosed and said the study saved her life.

Lascelle was a smoker for 27 years before quitting at the age of 41. Her parents were also smokers and her father died of lung cancer months after the disease was discovered at Stage 4.

"I know how quickly it normally goes," she said, adding she's volunteered in hospice care with people her age and younger dying as a result of the disease.

After the first CT screening in 2011, doctors noticed a small lesion in her lung that a biopsy would confirm was cancer. Lascelle said she had surgery soon after, which removed 15 per cent of her lung capacity, but no further chemotherapy or radiation was needed.

Having no significant symptoms and leading an otherwise healthy lifestyle when taking part in the study, Lascelle said she believes this screening process caught the disease that would have otherwise gone unnoticed.

"I don't believe it would have been looked at until it was a problem," she said. "I did ask when it was found would this lesion have been found with a regular (chest) X-ray ... and the answer I was given was likely not because it was very small."

Lam said lung cancer screening isn't widely available yet in Canada and patients currently need to have symptoms to be sent for testing.

A pilot project based on the Pan Can model has been launched at three sites in Ontario, Lam added, and screenings can be done through the study site in Vancouver.

Although smoking rates among the population has declined, Lam said he wants to see this screening model developed nation-wide to catch potential cases while it's treatable.

The study, which was funded by the Terry Fox Research Institute and Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, was published Wednesday in the journal The Lancet Oncology.