TORONTO -- It can wake a person up in the middle of the night and make the day a misery, with frequent episodes of belch-ridden indigestion, a burning sensation in the esophagus and throat and, for some people, radiating chest pain so severe they wonder if they're having a heart attack.

This all-too-common condition is known as GERD, for gastroesophageal reflux disease, often referred to more simply as acid reflux -- or really, really bad heartburn.

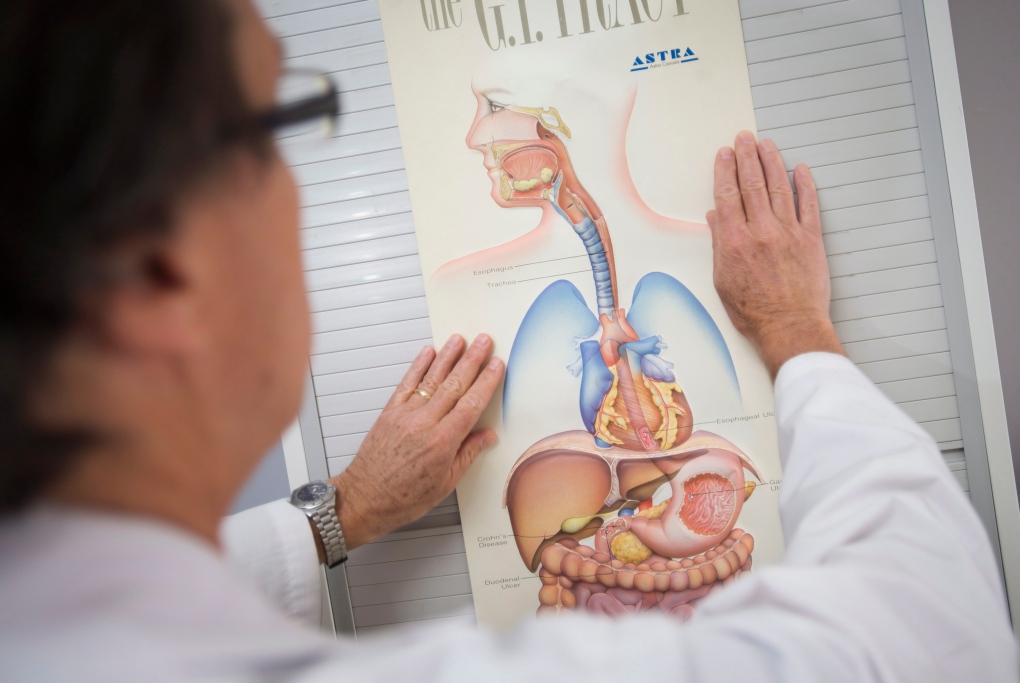

GERD arises as a result of stomach contents backing up, or refluxing, into the esophagus, the tube-like structure that connects the throat to the stomach. These backwashed caustic stomach contents -- acid, bile, pancreatic secretions and semi-digested food -- irritate the lining of the esophagus and can lead to chronic symptoms.

Besides heartburn, other symptoms may include difficulty swallowing, dry cough, a hoarse voice, regurgitation of food or a sour-tasting liquid, and feeling as if there's a lump in the throat.

While many people with GERD complain about feeling a searing or burning pain, some will experience deep, radiating pain caused by spasm of the esophagus that can be "excruciating," says Dr. Lawrence Cohen, a gastroenterologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto

"People fear they're having a heart attack, and it can be quite debilitating," he says. "I think there's more disruption than we think in terms of quality of life and productivity related to reflux."

GERD is also common, affecting at least half the population at some point in their lifetime. Prevalence studies suggest about 20 per cent of North Americans experience heartburn or acid regurgitation once a week and about 40 per cent at least once a month. Cohen estimates that 10 to 15 per cent of people struggle with symptoms daily.

The culprit at the root of GERD is a dysfunctional lower esophageal sphincter, a ring-like muscle that acts as a gate, opening to allow food and liquids to enter the stomach, then closing to keep them there.

But if that valve-like structure becomes weak or relaxes too frequently, allowing stomach contents to repeatedly back up into the esophagus, the result can be GERD, says Cohen.

This continuous reflux can cause the esophagus to become inflamed, and over time may erode its lining, causing such complications as bleeding, narrowing or a precancerous condition called Barrett's esophagus. In rare cases -- less than one per cent -- Barrett's esophagus can lead to a type of esophageal cancer called adenocarcinoma.

Cohen says some people with connective-tissue disorders, such as scleroderma, are more prone to GERD; some medications, among them non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and certain heart drugs, can also cause relaxation of the esophageal sphincter and the subsequent development of acid reflux disease.

In most cases, though, GERD is a product of lifestyle.

"The majority, I dare say, is directed by our habits, by our weight, our eating patterns, the content of our diet, and certain vices like smoking," says Cohen. "Those are the things that contribute to excessive reflux."

Being overweight -- especially around the waistline -- can promote the development of GERD because increased intra-abdominal pressure can send acid and other stomach contents shooting up into the esophagus, he says.

Other habits, such as eating large, high-fat meals late at night and then lying down, can also play havoc with the esophageal sphincter, which becomes subject to the laws of physics.

"So gravity -- you're lying down with a full tummy, especially after drinking some alcohol, having a nice restaurant meal with a lot of fat because fat is flavour," says Cohen, sketching out a common scenario that can start the GERD ball rolling. "Your stomach doesn't empty and it goes back up into the esophagus."

In fact, a whole range of foods can aggravate acid reflux, from citrus and tomato-based products to chocolate and the caffeine in coffee, tea and colas.

Gerald Birnbaum finds the food item most likely to make his GERD symptoms flare is tomato sauce. When his wife makes pasta, for instance, he knows to limit his portion size or face the consequences.

"I know if I eat too much, it's going to be a tough night ahead. I'm getting burning during the night; I'm getting burping. I can't lie down; I have to sit up," says the 78-year-old retired accountant, explaining that the fiery acidic backwash from his stomach can cause him to choke.

Birnbaum started getting symptoms in his mid-40s, while working as a senior partner in a high-stress environment of a large accounting firm.

"And I frankly ignored it. I thought it was just heartburn, there's nothing to be done and that was that," he says from his home in Thornhill, Ont., just north of Toronto.

"If I had been smarter, I would have got treatment much sooner, but I didn't even realize they could treat this stuff. I thought it was just how it was."

By his late 40s, Birnbaum started having repeated episodes in which he felt weak and faint. Tests revealed he was anemic, and a gastric examination with a scope showed he had developed ulcers of the esophagus, which were bleeding.

He was given medication and the ulcers have since healed. But Birnbaum knows if he overindulges by eating too much or eating too late in the evening, "I pay for it."

Cohen says there are a number of treatments for GERD that can resolve the condition, depending on its underlying causes and severity.

"We always step back to the motherhood issues of diet, lifestyle and weight, and once we address those we look at the spectrum of treatment," he says, pointing to antacids as the first step in trying to quell reflux and its resulting heartburn.

Recommended medications can range from one of the myriad brands of over-the-counter antacids like Tums, Gaviscon and Mylanta to prescription drugs known as proton pump inhibitors, or PPIs, among them Losec, Nexium and Prevacid, and their generic equivalents.

In some cases, doctors prescribe drugs called prokinetics, which work by stimulating the stomach to empty to prevent reflux; in others, a patient with GERD that doesn't respond to antacids may be given the muscle relaxant baclofen to decrease relaxation of the sphincter.

Cohen said that for some patients with stubborn GERD symptoms, surgery may be the best treatment option, although only about one per cent are good candidates for the operation that involves "wrapping a bit of stomach around the lower esophagus and tightening it up."

Still, Cohen goes back to altering one's habits as the first line of defence for treating GERD and preventing its return.

"We can reverse and modify frequency of reflux by looking at those factors of diet and lifestyle," he says. "And we can change it from chronic to intermittent to resolved."