WINNIPEG -- A Winnipeg hospital emergency room was overcrowded and short-staffed -- operating without a key triage nurse -- when a man who died during a 34-hour wait came in seeking care.

Susan Alcock told an inquest into the death of Brian Sinclair that the emergency room at Health Sciences Centre was short five nurses on Sept. 19, 2008. They were only able to fill two of the vacancies, so Alcock said a nurse who would normally triage patients and reassess their condition while they waited was reassigned when Sinclair first arrived at the hospital that afternoon.

"When you have that many shortages, it really impacts on the care you can give to patients," said Alcock, a senior clinical resource nurse who has worked at the Winnipeg hospital for 21 years.

At the time, Alcock said they were also dealing with more patients than normal -- 134 patients were admitted on Sept. 19 and 138 triaged the following day. The average patient load was around 120 a day, Alcock said.

"Both of those shifts were horrific," she said Monday. "We were full."

The reassessment nurse was a position created following the death of another woman in the emergency room in 2003 and following recommendations of a task force in 2004, she said.

"People are at risk when they wait," she told the inquest. "Incidents had happened so that's why they got us a reassessment role."

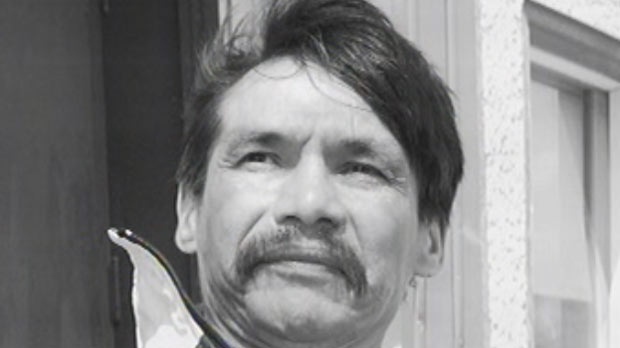

Sinclair was referred to the emergency room by a community doctor because he hadn't urinated in 24 hours. Sinclair -- a double-amputee -- spoke to a triage aide when he first arrived on Sept. 19 and wheeled himself into the waiting room where he languished for the next 34 hours.

Despite vomiting several times while his condition worsened, Sinclair was never officially triaged or examined by a medical professional until rigor mortis had set in. An inquest is examining why the 45-year old died of a treatable bladder infection without receiving medical care.

Manitoba's chief medical examiner testified Sinclair would have required about half-an-hour of a doctor's time. His catheter needed changing and antibiotics prescribed.

Alcock said she knew Sinclair since he was a frequent visitor to the emergency room over the years, often for issues relating to substance abuse. Alcock said she was also Sinclair's bedside nurse when he was admitted to the hospital in 2007 after being found frozen to the steps of a church in the dead of winter.

"I will never forget his legs," she said, her voice trembling with emotion. "They were frostbitten up to his knees. They were like a block of ice."

Sinclair's legs were amputated as a result.

It's not unusual for the emergency room to operate with only 80 per cent of positions filled, Alcock said. Nurses are juggled around to fill the most necessary vacancies, she said.

Often, she said nurses who are reassigned to the emergency room to fill a vacancy aren't fully qualified to work there.

"You need special training to work competently in the emergency room," Alcock said. "They just don't have the experience we have."

The inquest is scheduled to sit for the rest of the month and hear from other nurses and medical staff who were on duty at the time.