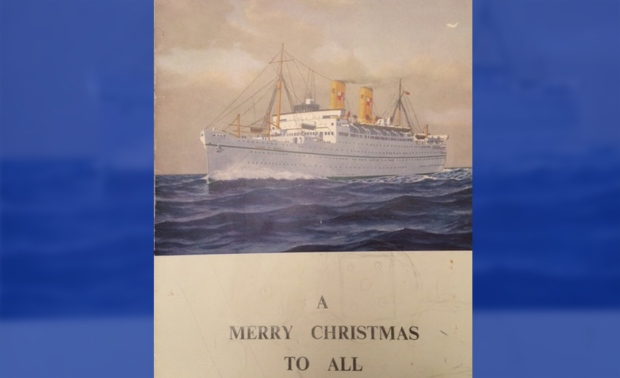

On December 19, 1956, my mother Kati, a then-six-year-old Jewish girl from Budapest, Hungary celebrated Christmas at a party aboard S.S. Empress of France as it crossed the choppy Atlantic waters en route to her new home – Canada.

It was the final leg of a journey that began five weeks earlier, under much less festive circumstances: As choppers circled overhead and gunfire rang out on the streets of Budapest in early November, her family – parents Olga and Imre and her nine-year-old sister Judy -- made arrangements to leave the country.

"There was a lot of shooting outside," my aunt Judy remembers. "It felt like we were in the war."

One morning at dawn, they packed some belongings in bags, left their apartment at 56 Akacfa Street and headed to the train station.

Their destination, as it was for thousands fleeing the violence spurred by the Hungarian Revolution, was Austria. They managed to make it to a border town while evading detection by Russian soldiers and Hungarian secret police and other possible informants lurking about. There, my grandparents searched for guides who would safely move them across the Austria-Hungary border under the cover of night.

Damaged buildings are seen opposite the Maria-Theresia Barracks in Budapest, Hungary in this Nov. 16, 1956 file photo. (Associated Press)

Frightened by what she’d heard about the experiences of others who had been robbed or abandoned at the border, my mother turned to my grandmother and declared that she wanted to go back.

“I begged her to go home because I was scared,” my mother now says.

But there would be no going back. That day, in a strange town and a strange house with bunk beds, my mother and her family slept fully clothed, uncertain of what the future held.

At nightfall, they rose to leave with hired guides, lugging anything they could carry, to begin a 15-kilometre walk in fields and swamps. Along the way, they barely escaped the detection of a Soviet army truck that passed them by, flashing their headlights in their direction before speeding off.

When they arrived at a broken bridge over a creek, my grandparents abandoned their few possessions in order to climb across on all fours. My mother left behind her beloved slippers as she was lifted onto my grandfather’s back.

When they finally reached city lights, my grandparents knew they had made it to the Austrian border: The lights illuminated the tears in my grandfather’s eyes.

Canada’s unprecedented contribution

Sixty years later, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 is a brutal chapter in the history of Communism in Eastern Europe.

It’s also the story of Canada’s unprecedented generosity toward refugees in crisis. In just mere months, the government under then-prime minister Louis St. Laurent gave asylum to approximately 37,000 refugees who fled Hungary. The operation forever changed the way Canada would process refugees fleeing violence or war-torn homelands.

Life in Hungary during the Cold War was “pretty much hell,” says Tibor Lukacs, executive director of the Oral History Project at the Rakoczi Foundation, an organization dedicated to preserving Hungarian cultural traditions in Canada.

“Everything was stifled,” said Lukacs, a refugee himself, who spent two years in an Austrian refugee camp before entering Canada through Pier 21 and resettling in Toronto. “And it made the people become aware that this simply cannot go on.”

Like many citizens of countries under Communist rule, everyone in Hungary lived under a cloud of suspicion. The oppression of a tyrannical empire affected their daily lives.

“The system was so bad, that if they pinned something on you at any time, they would come in the middle of the night … they would knock at the door, and they said, ‘You have five minutes to get your things, you’re coming (with us),’” Lukacs said. “They never said why, how, where.”

Sometimes, families would never see their loved ones again, he said. There was hope for change when young Hungarians, many university students, labourers and intellectuals, held a peaceful demonstration in Budapest on Oct. 23, 1956. Hundreds joined in the demonstration, calling for democracy and for days afterward, it seemed that they may have achieved their much-sought after liberty from an oppressive regime.

But on Nov. 4, in an extraordinary show of force, Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest, effectively crushing the revolt and dimming any hope of change. As the streets of Budapest transformed into an open battlefield, residents did more than lose faith; they began making plans to escape. According to the UN Refugee Agency, from Nov. 4-6, some 10,000 Hungarians streamed into Austria – “Entire classes – even entire schools – began crossing the loosely guarded border,” one document read.

Rebels wave their red, white and green national flag from a tank captured in the main square of Budapest, Hungary, in this 1956 file photo. (AP)

As pictures and footage of a shelled Budapest emerged, the plight of the refugees streaming out of Hungary captured the international community’s attention, including Canada’s.

Lukacs, as well as many Hungarian refugees, credits then-Canadian Immigration Minister Jack Pickersgill for his leadership on the file. According to government documents, on Nov. 6, 1956, Pickersgill ordered the Canadian immigration office in Vienna to assign “top priority” to applications from Hungarians hoping to emigrate to Canada. Weeks later, Pickersgill arranged for the safe passage and processing of Hungarian refugees.

Pickersgill did so to ensure that the “system" of bringing in refugees "was expedited,” Lukacs said.

At one point during the months-long operation, the Canadian government was processing Hungarian refugees into the country “almost every minute,” Lukacs said.

Refugees would come in by chartered ships, and arrive at Pier 21 in Halifax, the federal immigration depot in Saint John, New Brunswick or other entry points where they would be processed.

“No country accepted as many Hungarians as Canada did,” said Lukacs, now a 71-year- old retired schoolteacher. “No one.”

Indeed, countries like the United States, Yugoslavia and Israel accepted Hungarian refugees but it appears none to the scale of the Canadians. “It was good that they did, because they realized that the people who came, they were in dire need,” Lukacs said.

More impressive was that the organized efforts came just six years after Canada’s Citizenship and Immigration Department was even established.

In some ways, my mother and her family were even luckier than those who were processed without any documentation or official immigration papers.

Just days after my mother attended the ship Christmas party, they docked in Saint John. Waiting for my mother and her family in Montreal was N.J. Fodor, a Hungarian manufacturer who had arranged for a job for my grandfather, a lens grinder. My grandmother had worked for Fodor as a bookkeeper in Budapest, where he was a director at a General Electric subsidiary.

A Christmas card given to passengers aboard S.S. Empress of France in December 1956.

However, during the train ride to Montreal, immigration officials didn’t let them off the train, and instead they continued on to Ottawa with the rest of the refugees aboard the train.

The mix-up was soon resolved, but not before the Canadian media turned out to capture the story. Today, the newspaper clippings about their unusual arrival are family mementos:

A newspaper article about the mixup with immigration officials after the Ban family arrives in Canada in December 1956.

My mother, Kathy (Kati) is now a 66-year-old mother of two grown children – my brother Matthew and me. A librarian, she lives with my father Robert in Toronto, where they moved with my brother in 1980, a year before I was born. Her sister Judy (Judit), a married mother of three and grandmother of two, still lives Montreal.

My mother would often tell me the story of how she escaped from a place called Hungary. I considered it the best bedtime story of my childhood and frequently asked her to repeat it, snuggled up cozy in my bed.

For my mother, it was hard to forget: For years, seeing headlights in the distance on a road brought back intense reminders of the near-encounter with the Soviet army truck. If they had been caught, it’s likely my grandparents would have been sent to prison – or worse.

Most of all, my mother and aunt remember the strength and courage of their parents, who had already lived through the horrors of the Holocaust when they left for Canada.

“They were middle-aged already, so they started over with two young kids and a big unknown,” my mother says. “They didn’t know what life was going to be like here in Canada, whether there would be room for them, or jobs.

“I guess whatever they were coming to had to be better than what they were leaving behind.”

My mother’s words echo her mother’s words to the Montreal Star, which published an article about their arrival on Dec. 27, 1956: “It may seem strange we could be happy giving up everything we ever had,” my grandmother told the newspaper. “But we never made a better move.”

A Montreal Star article published on December 27, 1956 highlights the Ban family's journey to Canada.

My grandparents, Olga and Imre Ban, worked in Montreal as a bookkeeper and optician, respectively, to provide for their daughters’ education and until they had enough money to retire comfortably. They knew all five of their grandchildren, and visited Toronto frequently after my mother moved her young family there.

In their duplex on Clanranald Avenue in Montreal, my grandparents kept a shrine of the kids’ handprints, class photos and artwork. They never owned a car, but they travelled, even visiting Hungary with my mother in 1969.

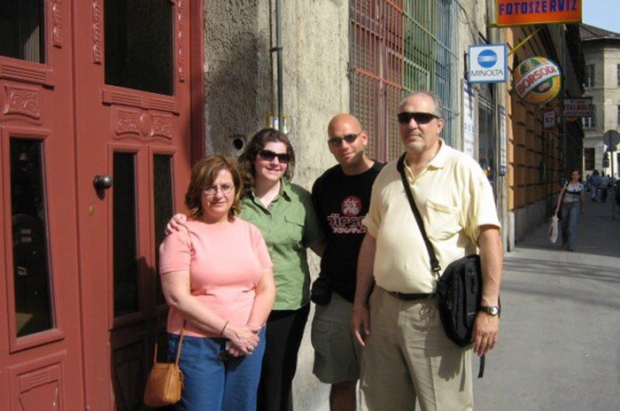

In 2007, my mother would travel back again to Budapest -- this time with her husband and two children -- where we visited the apartment complex at 56 Akacfa Street.

By then, both my grandparents had long since passed away. They are buried side by side, in the Hungarian section of a cemetery in the Cote-des-Neiges neighbourhood of Montreal.

Kathy Coorsh (nee Ban), left, and her family pose in front of her childhood home in Budapest, Hungary in May 2007.