Jamie Margolin had not expected to be sitting in her bedroom right now.

The high school senior had prom and graduation coming up, but so much more: A multi-state bus campaign with fellow climate activists. A tour for her new book. Attendance at one of the massive marches that had been planned this week for the 50th anniversary of Earth Day.

Then the pandemic arrived in Seattle, her hometown, and her plans went out the window.

"But still so much to do," Margolin said, perched in front of her computer for a video interview from that bedroom.

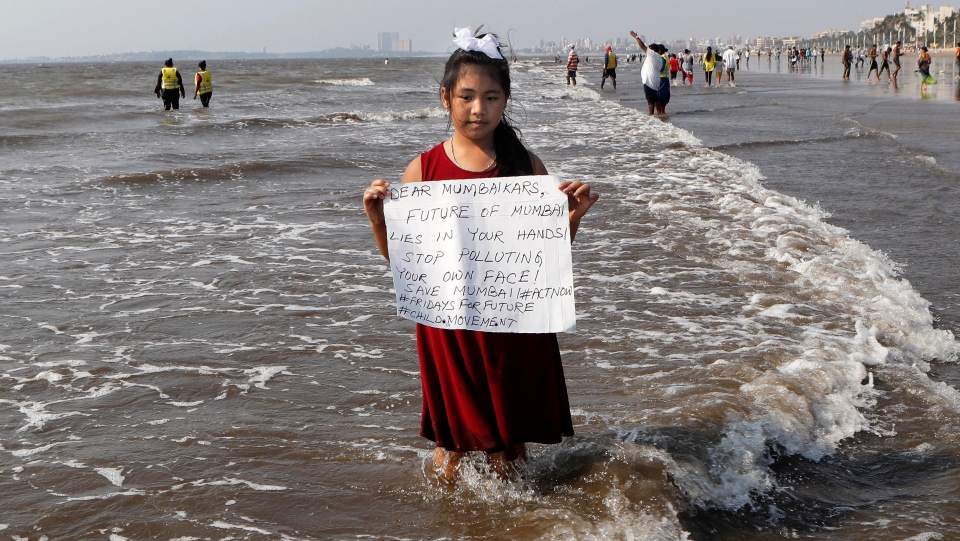

Like many other young activists who've helped galvanize what's become a global climate movement, Margolin is not letting a spreading virus stop her. They are organizing in place, from the United States to Ecuador, Uganda, India and beyond.

And while some fear they've lost some momentum in the pandemic, they are determined to keep pushing -- and for now, to use technology to their advantage.

Unable to gather en masse as they'd planned this Earth Day, these activists are planning livestreams and webinars to keep the issue of climate front and centre on the world stage and in the U.S. presidential race.

One event, Earth Day Live, is being organized by a coalition of youth-led climate groups, including Zero Hour, of which Margolin is a leader (her Twitter profile includes the tag .futurepotus). As is the case with many other young climate activists, she got involved in the movement taking aim at the fossil fuel industry well before Sweden's Greta Thunberg became a global household name.

Online organizing is not as easy in some countries. In Uganda, activist Mulindwa Moses says only about a third of the population has Wi-Fi. Also under lockdown, the 23-year-old graduate student is waiting for his chance to return to planting trees and speaking to his nation's youth in person.

Like the original founders of Earth Day, he is among those who were first inspired by local issues -- which they came to connect with global climate change.

While travelling in eastern Uganda, Moses met with families who had lost their homes in mudslides caused by torrential rainfall.

"I remember a girl I had a conversation with -- she lost her parents and had to take care of her siblings. She was suffering so much," he said.

So, last year, he began a campaign to encourage citizens to plant "two trees a week" and regrow their forests to combat deforestation and mudslides exacerbated by changing weather patterns.

In Ecuador, 18-year-old Helena Gualinga also has had to pause her world travels.

Born in Ecuador's indigenous Kichwa-speaking Sarayaku community -- home to about 1,200 people in the Amazon -- she says she learned from the example of her parents and her elders how to speak up for the rights of her people. Their fight has been against a government that they believe has given their land too freely to mining and oil companies.

"The energy I remember from my elders growing up" -- at community meetings she attended with her parents when she was small -- "was that my community was always very worried," she said.

Now, she added, "I know I have a voice."

Moses plans to run for his country's parliament next year. "I want to fight to change the system from the inside," he said.

So does Max Prestigiacomo, a freshman at the University of Wisconsin, who is set to take his seat on the city council of Madison, Wisconsin. While fighting the coronavirus has used up much of local government's bandwidth, he still plans this fall to push the platform on which he ran -- for his city to become fully sustainable by 2030. It is a lofty and some would say unattainable goal, but he is looking for "the impossible yes."

"Obviously, I wanted the alarm sounded decades ago before I was even born," the 18-year-old said. "But it's too late for incremental change."

Tia Nelson, daughter of the late Sen. Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, founder of Earth Day, said her father would appreciate the determination of this generation, as he did the young people who made the first Earth Day in 1970 a great success.

Though the senator went to Washington in 1963, and won support from President Kennedy, his daughter said it took several years to find backing for many of his environmental causes. He came up with the idea of Earth Day, first envisioned as a nationwide "teach-in," after reading a magazine article about college students' impact on U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

Later that same year, the Environmental Protection Agency was born.

"The climate youth movement today is having a significant and important impact in doing exactly what my father had hoped on the first Earth Day -- that he would get a public demonstration sufficiently robust to shake the political establishment out of their lethargy," Tia Nelson said. "The youth movement 50 years ago did that. The youth movement today around climate change is doing the same thing."

Nelson, who is climate director at the Wisconsin-based Outrider Foundation, said she's particularly excited at polls showing that many young Republicans care just as much about climate change as Democrats.

Peter Nicholson, who helps lead Foresight Prep, a summer environmental justice program at Chicago's Loyola University, said the coronavirus crisis only highlights the message that "we are all connected."

"Climate change is no less real," he said. "The feedback loop is just much longer."

So for now, Margolin and her peers will use their devices to help foster those connections -- something their predecessors could not do remotely.

"Everyone is online anyway," she said. "Maybe they start on Earth Day. But then with online resources, you click one link that leads you to another, leads to another that leads you to contact info."

"And then you just start getting involved."

Martha Irvine is an AP national writer and visual journalist. Christina Larson is an AP global science and environment writer.