On a warm summer night in Saskatchewan, about an hour south of Regina, crowds gather in the small town of Bengough to see one big Canadian name – a headliner for the Gateway Music Festival. At 82 years old, Ian Tyson can still draw a crowd.

Backstage, Tyson runs through the vocal warm up routine he’s done countless times throughout his five-decade-long musical career. He stretches his arms and legs. And then his vocal cords. He tunes his guitar and then saunters to the big stage, peeking out at the crowd.

At 9:30 pm he takes the stage. His voice picking out just the right notes. His fingers picking out the chords. And sings his songs about the west. Not the honky-tonk over-produced country and western twang, but real ballads about places and legends, and a world that is slowly vanishing.

Songs about selling out the ranch. About moving horses to overwinter in Arizona. About how Charles M. Russell painted vast landscapes of a vanished world. And of simple things, like how Tyson himself was inspired to be a cowboy.

Ian Tyson didn’t start out to be a musician and singer. In the late 1950s he went to art school in Vancouver and on weekends was riding rodeo in British Columbia and Alberta. He’d gotten the cowboy bug when he was placed on a horse in Duncan, B.C. when he was but a child.

Then a lucky break, literally, turned him onto music. He was thrown while riding a bronc in a rodeo completion and his ankle had been crushed. While recovering in a Calgary hospital, Tyson picked up a guitar that belonged to his hospital roommate. Tyson started strumming along to a song that kept playing on the radio, Johnny Cash’s Walk the Line.

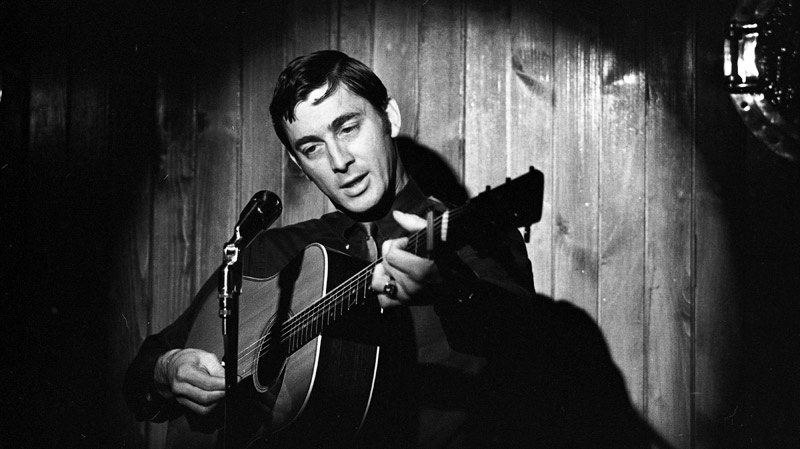

It wasn’t long after that Tyson, now with a guitar of his own, packed his bags and hitchhiked east to Toronto, where the folk music scene in Yorkville was just starting to emerge.

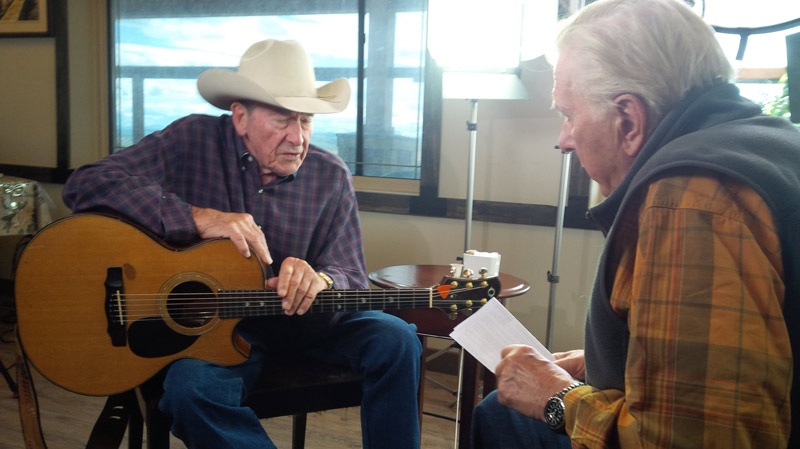

“The folk thing was just hitting big,” Tyson told W5’s Host and Chief Correspondent, Lloyd Robertson, in an exclusive interview. “It was so intense that there were more singing gigs and coffee houses than there were people to sing in them.”

Tyson kept booking gigs and soon he met Sylvia Fricker. The pair teamed up, forming the legendary folk duo Ian & Sylvia. Not just partners on stage, the two married in 1964.

Their success moved beyond Canada and brought them to New York City in the 1960s, where they hung out with other young budding musicians. One of those young artists was Bob Dylan. “He was kind of funny and nobody took him seriously,” said Tyson. “But after about a year they really started taking him seriously.”

It’s long been rumoured that Tyson was the man who gave Bob Dylan his first joint. “It may be true,” laughs Tyson. “You know, I’m not gonna deny it.”

It was there in New York where Tyson wrote what would become his most popular song, Four Strong Winds. The song, written about love and the West, has resonated with Canadians for generations, even earning the title of “Greatest Canadian song” in 2005.

The entire country watched as Tyson performed Four Strong Winds at a memorial service for four slain Mounties in Mayerthorpe, Alberta that same year. Earlier in 2015, Tyson put out a music video with the Naden Band of the Royal Canadian Navy as part of a project for Heritage Canada, marking the 100-year anniversary of the First World War.

“It was about my first love, my first girlfriend from art school,” recalled Tyson. “She was a Greek girl from the Okanagan. Lovely, beautiful, beautiful woman and ah we fell in love and we damn near got married, but we didn’t.”

After recording and performing across North America with Sylvia in the 1960s and early 1970s, Tyson came back to Toronto and starred in the Ian Tyson Show on CTV. The country music show helped kick off his solo career and around the same time, his marriage to Sylvia came to an end.

“She wanted to live in Toronto and I wanted to be in the West,” he said. We remained pretty good friends to this day.”

Tyson left the city in the late 1970s, moving back west and buying a ranch south of Calgary in the foothills of Alberta, a quiet refuge that he still calls home today. He played steady gigs at the legendary Ranchman’s in Calgary, where he met his second wife, Twylla.

“She loved those old ballads,” said Tyson. “She just loved them. And she’d always encourage me. People when they heard those songs, and I think this is – the cowboy revival – I think this is the key to it. People when they heard these songs, they would fall in love with (them). Because, you know, they are literature and they have withstood the test of time.”

The cowboy way of life

He continued writing music and living the cowboy way of life. Tyson has been going down to Elko, Nevada every year for the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering since it started in 1985. “You get some of the buckaroos from different parts of northern Nevada and come to Elko and you know, get some whiskey and have a hell of a good time.”

Tyson says those poetry gatherings gave his career a re-boot in the mid-1980s. “America was in love with the urban cowboy,” said Tyson. “It was a huge success.” His following album, Cowboyography, won Tyson a Juno award for country male vocalist of the year in 1987.

While Tyson sings about being a cowboy and his love for the west, for decades he has used his voice for political and environmental causes – publically protesting dams and oil and gas wells in Alberta. And he’s still speaking out. On his most recent album, Carnero Vaquero, which was released in 2015, Tyson penned anti-fracking song called Cottonwood Canyon. “It’s apparently the favourite song on the album” says Tyson. “Which really pleases me.”

More than fifty years since he first picked up a guitar, cowboy Ian Tyson still enjoys writing songs about what he’s most passionate about. “I love to sing,” he said. “I like it more than ever.”

Walking across his ranch Tyson looks at his corrals, then out to the rolling foothills and toward the distant Rockies. “I just want to have enough country that I can stretch out and with my horses and my cattle and just live out my life here. And that’s about it. I don’t have any grandiose plans for the future.

Except perhaps continuing to perform his cowboy ballads and – more than five decades after first finding fame as a folk singer – continuing to entertain audiences with his unique blend of music.