When Deane Daprato was born in Toronto in 1998, his parents Mark and Ijeoma were given a frightening diagnosis: Spastic Quadriplegia, a type of cerebral palsy.

“You’d go out with your friends and you’d see their kids playing and you just knew that wasn’t part of your reality,” Mark Daprato told W5.

Over time, Mark and Ijeoma realized Deane would never be able to walk, talk, and feed himself, or do anything on his own. His stiff muscles would have to be regularly massaged; even swallowing and breathing would need to be closely monitored. Caring for Deane would be a challenge.

But Ontario government services were there for the Dapratos.

From the time Deane was little, an army of specialists has been dedicated to his well-being; teachers, physiotherapists, occupational and speech therapists, psychologists and pediatricians. Everything he needed.

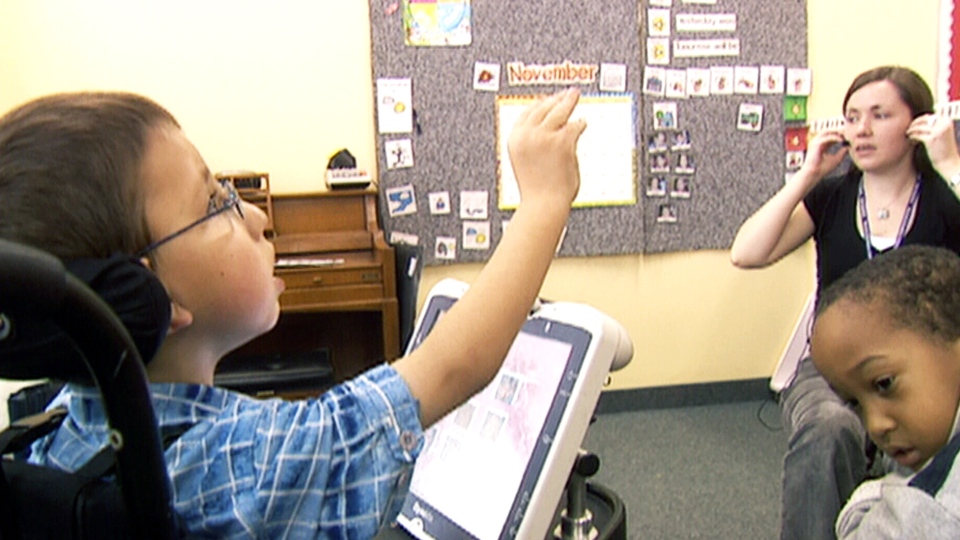

W5 first caught up with Deane Daprato when he was six-years-old and a day student at what was then called Bloorview McMillan Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

A team of seven people addressed all of his physical and emotional needs. Activities as routine as eating lunch were carefully monitored. Back then, Deane had a huge infrastructure, watching his every move.

(A W5 documentary “Help & Hope” that aired in 2005 followed his care and that of other children at what was then known as the Bloorview MacMillan Children's Centre. You can watch it in our video player above).

Fast forward and Deane is now 19. Last year, the government began gradually withdrawing funding and services. By the time he is 21, he will have aged out of the program completely. No access to school, or the team that made life easier for Deane and his parents.

“You have to go into the adult system,” explained Ijeoma. “All of the doctors and services, not all exist in the adult system. You now have to start again from square one.”

The Dapratos have been navigating the complicated maze of government agencies in charge of funding for disabled adults.

“It’s a very adversarial system (that’s) backlogged, red taped, basically has left us from having a significant chunk of money to provide respite care,” Ijeoma told us.

It means that unless funding comes through, the Dapratos will have to look after Deane on their own, from dawn to dusk. A shortage of group homes and long waitlists means the option of adult living for Deane is way down the road, if ever.

It frightens Mark. “What we really want is the ability to have as much as we (did) when (Deane) was growing up,” he said.

They are not alone.

When the provincial government closed institutions for the physically disabled, it left care to the families. This is the first full generation of severely challenged non-institutionalized adults needing care.

The Dapratos are calling for fundamental legislative change, because, as Mark told W5: “The funding formula is wrong. (It) doesn’t take into account that for generations, severely disabled adults were in institutions.”

What worries Mark and Ijeoma the most: Who will look after Deane when they are too old, or gone?

“I think the image that keeps me up at night is Deane sitting in front of a TV somewhere with, you know, maybe there’s a caregiver somewhere, but no one’s actually interacting with him,” said Ijeoma.

There are solutions.

You can learn what some of them are on CTV’s W5 Saturday at 7pm