A quarter of the world’s population is faced with the dire prospect of running out of water as demand outpaces supply and climate change takes its toll, according to new data.

On Tuesday, the World Resources Institute (WRI) published a ranking of the countries with the highest water stress based on 13 indicators, including groundwater availability, water depletion, rainfall variability, and water regulation.

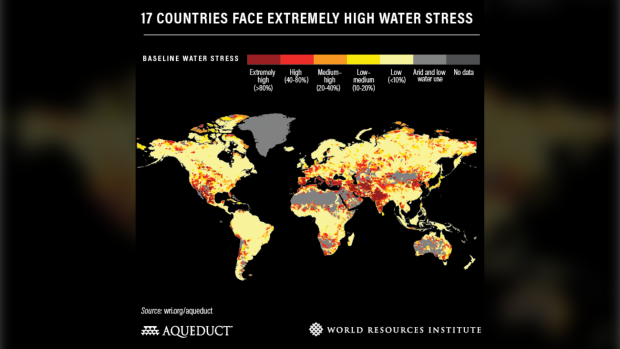

Using updated data from WRI’s Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas tool, researchers revealed that 17 countries are facing “extremely high” water stress, meaning they’re drinking up 80 per cent of available surface and groundwater in an average year. That means that even the smallest “dry shocks,” which are becoming more frequent due to climate change, can lead to “dire consequences,” the authors note.

“Water stress is the biggest crisis no one is talking about. Its consequences are in plain sight in the form of food insecurity, conflict and migration, and financial instability,” Andrew Steer, WRI’s president and CEO, said in a statement.

“Failure to act will be massively expensive in human lives and livelihoods.”

The organization cited population growth, socioeconomic development, and urbanization as contributing to increasing demands for water while climate change has made precipitation and droughts more variable.

“Such a narrow gap between supply and demand leaves countries vulnerable to fluctuations like droughts or increased water withdrawals,” the authors said.

Countries at risk

Qatar, Israel, and Lebanon topped the list of 189 countries as the most water stressed while Suriname, Liberia, and Jamaica had the lowest. Canada also had low water stress and placed 108th in the ranking.

The research organization noted that the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has become a hot spot for water stress around the world, home to 12 of the 17 most at-risk countries. WRI attributes the lack of supply in this region to its hot and dry climate and growing demands.

“Experts have pinpointed water scarcity as a force that can exacerbate conflict and migration,” the U.S.-based think tank said.

WRI said there is hope for the region, however, if countries work to boost their water security by reusing wastewater. Currently, approximately 82 per cent of the region’s wastewater is not reused.

The researchers pointed to Oman as an early leader in this field. The country, ranked 16th in the list, currently treats 100 per cent of its wastewater and reuses 87 per cent of it.

India was also singled out as a country of particular concern for the research organization.

In June, government officials for the country’s sixth-largest city of Chennai declared it had reached “Day Zero” – a term used to describe the day when the taps run dry – following weeks of soaring temperatures and drought. And while the city continues to make international headlines as it struggles through a serious water shortage, the problem extends well beyond the city’s limits.

“The recent water crisis in Chennai gained global attention, but various areas in India are experiencing chronic water stress as well,” Shashi Shekhar, the former secretary of India’s ministry of water resources and a senior fellow at WRI India, said.

The country ranked 13th for overall water stress and has more than three times the population of the other 16 "extremely highly” stressed countries combined.

Last year, an Indian government research agency announced the country is “suffering from the worst water crisis in its history, and millions of lives and livelihoods are under threat.”

In response, WRI said India can manage its water risk by revamping its irrigation system to be more efficient, conserving and restoring lakes, floodplains, and groundwater recharge areas, and collecting and storing rainwater.

Finally, the study also examined the range of water risk within countries to demonstrate that even countries with a low overall ranking in the list could still have “pockets” of extreme water stress.

For example, the United States placed 48th with a low to medium water stress level; however, the state of New Mexico had an extremely high stress level. In South Africa, which was 71st on the list, the Western Cape was also declared extremely at risk.

“The populations in these two states rival those of entire nations on the list of most water-stressed countries,” WRI said.

Despite the grim warnings, WRI said countries can bolster their water security through proper management. Water stress can be reduced by increasing agricultural efficiency, such as planting crops that require less water and improving irrigation techniques. Countries can also invest in infrastructure, such as pipes, treatment plants, wetlands, and healthy watersheds.

Additionally, treating, reusing, and recycling wastewater can go a long way in creating “new” water sources.

“There are undeniably worrying trends in water. But by taking action now and investing in better management, we can solve water issues for the good of people, economies and the planet,” the WRI said.