TORONTO -- Stunning new images of deep canyons and spidery frost deposits on Mars, plus new gassy discoveries, are rocking the science world in a month already full of red planet news.

This past summer, three new Mars expeditions began -- a new NASA rover, China’s first rover, and an orbiter from the United Arab Emirates -- two of which arrived at the planet earlier this week, with the NASA rover set to touch down later this month.

Although they’ve garnered a lot of attention, they aren’t the only ongoing Mars projects.

In 2016, the European Space Agency’s ExoMars programme launched the Trace Gas Orbiter, armed with a camera called "CaSSIS" and a host of scientific instruments that help it search for trace gases to better understand the planet’s atmospheric makeup.

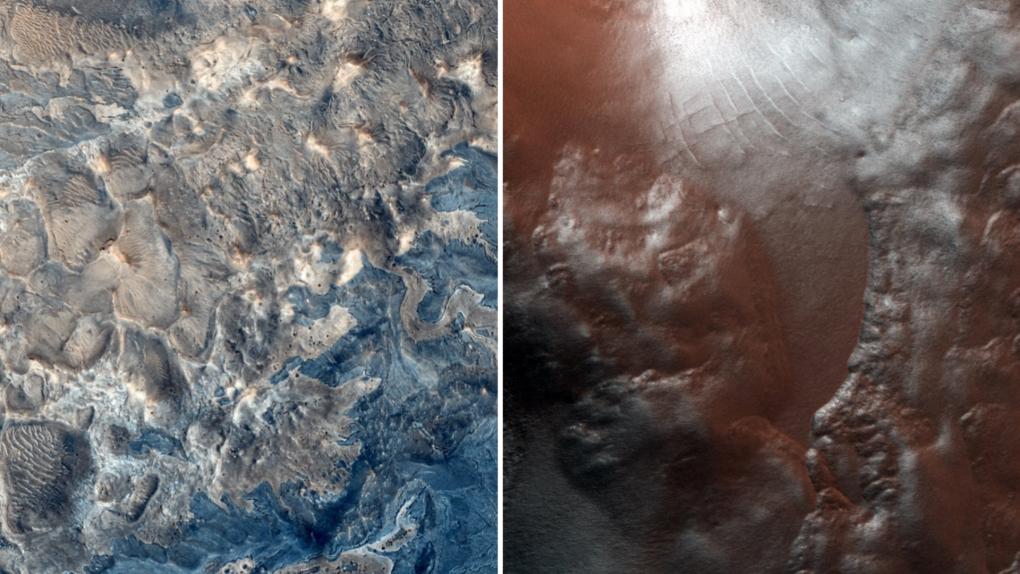

Since its launch, the orbiter has been busy. The CaSSIS camera has been taking extremely high-definition photographs of the planet’s surface, highlighting the geological structures and pockmarked surface of Mars in terrific detail. An Instagram account set up for the device showcases the best of its camera roll, with scientific explanations accompanying photos of various regions of the planet.

“Valles Marineris is a massive canyon over 4,000 km long and over seven km deep in places,” reads one Feb. 5 caption on a photo showing a rugged green and grey landscape. “This is about as long as the distance from Madrid to Moscow, and about six times deeper than the deepest parts of the Grand Canyon.”

'NEVER-BEFORE-SEEN' GAS

Possibly more groundbreaking than pictures from another planet is the detection of a new gas. For the first time, the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter has discovered halogen gas in the planet’s atmosphere. On Wednesday, the ESA announced that the orbiter found hydrogen chloride. The results, published in the journal Science Advances, found that sea salts on the planet’s surface, perhaps left behind by long-gone oceans, rise into the atmosphere through winds, where they react with water vapour rising off of ice caps to create hydrogen chloride.

“You need water vapour to free chlorine and you need the by-products of water -- hydrogen -- to form hydrogen chloride. Water is critical in this chemistry,” said Kevin Olsen, a lead scientist with the University of Oxford, said in a press release.

He added that hydrogen chloride in the atmosphere increases in response to large dust storms in the southern hemisphere.

“It is incredibly rewarding to see our sensitive instruments detecting a never-before-seen gas in the atmosphere of Mars,” said Oleg Korablev, principal investigator of the Atmospheric Chemistry Suite instrument on the orbiter. “Our analysis links the generation and decline of the hydrogen chloride gas to the surface of Mars.”

Trace gases makes up less than one per cent of a planet’s atmosphere, so the hydrogen chloride isn’t there in large quantities, researchers said. But the discovery provides new insights into the makeup of the red planet. ExoMars is learning more about the history of water on Mars by tracking water vapour as it rises into the atmosphere. According to researchers, the water vapour indicates that large amounts of water were lost over time on Mars, which supports theories that the planet once was home to much more water than is visible today in ice caps.

The ExoMars programme is set to launch a rover in 2022.