When the president of the A.V. Roe plant in Malton, Ont. came on the intercom in February 1959 to tell his workers that prime minister John Diefenbaker had just cancelled the Avro Arrow project, there was palpable disappointment among the world-class team of aeronautical engineers who were about to lose their jobs.

That is, until NASA came a knocking.

The cancellation of the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow, a supersonic interceptor jet to be used to protect Canada in the event of a Cold War-confrontation between the Soviet Union and the U.S., has been widely considered a setback for the country’s aerospace industry.

But Canada’s loss turned into America’s gain when NASA snapped up 33 of those out-of-work engineers to join a small team tasked with managing the country’s manned spaceflight programs.

Amy Shira Teitel, a Canadian-American spaceflight historian and author who has worked with NASA on the New Horizons Mission to Pluto, called the Canadian infusion a turning point for the U.S. agency’s Space Task Group.

Led by Robert Gilruth, NASA’s Space Task Group, which grew into today's Johnson Space Center, had the formidable challenge of figuring out a way to land an American on the moon before the Soviets.

Because space discovery was still very much an unpredictable profession at the time, many American engineers were reluctant to leave their jobs in aviation or other established industries to work for NASA.

“Gilruth couldn’t find any American engineers who wanted to join NASA, but he knew these Canadian guys were all of a sudden out of a job and he thought they were brilliant and professional and peak guys,” Teitel said during a telephone interview from Los Angeles on Tuesday.

In April 1959, the “brilliant and professional” Canadians, who made up a third of the Space Task Group, arrived at the Langley Research Center in Virginia to begin their new careers.

“It was a significant addition to the brain power of early NASA when they arrived,” Teitel said.

Jim Chamberlin

One of those brilliant engineers was a man from Kamloops, B.C. named Jim Chamberlin. He had worked on the Avro Arrow project for 13 years and was the project’s chief of technical design before joining NASA.

When Chamberlin joined the Space Task Force, Teitel said he quickly became one of Gilruth’s “most notable” advisors.

“He worked very closely with him to the point where he ended up really helping define the Mercury spacecraft,” she said.

The Mercury project was the first human spaceflight program in the U.S. and laid the groundwork for the subsequent Gemini missions, of which Chamberlin became the first program manager. The Gemini program ran from 1965 and 1966 and was the precursor to the Apollo missions.

“Jim Chamberlin oversaw the early development of the Gemini program,” Teitel said. “He ended up being a go-to problem solver for every element of that program. By that point, he’d been in at the ground floor, in the inner circles of NASA for so long, that he knew the stuff intimately.”

One of Chamberlin’s most important contributions to the spaceflight programs was his early enthusiasm for the lunar-orbit rendezvous (LOR) concept.

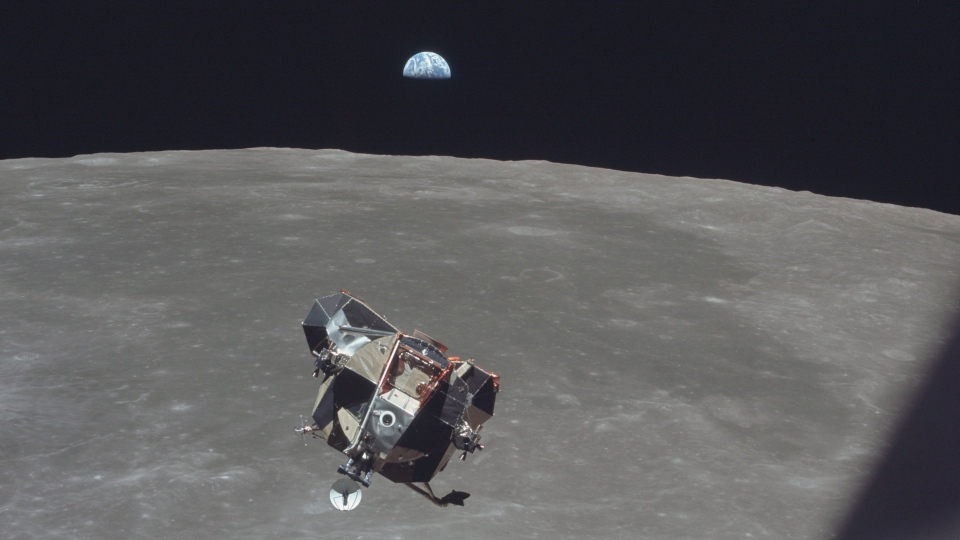

Aerospace engineer John Houbolt has been credited with creating the LOR concept, which involved sending three spacecraft into Earth’s orbit on top of a single powerful rocket. According to NASA, the assembly of three aircraft would include a mothership or command module, a service module containing fuel cells, and a small lunar lander, in which the astronauts would land on the moon.

“Not a lot of people liked the idea,” Teitel explained. “But Jim Chamberlin and another Canadian, Owen Maynard, were two of the first people with the Space Task Group who saw the value of this idea and started running with it.”

Chamberlin, as an important figure in the Gemini missions, helped develop the LOR method using a Gemini spacecraft as the mothership that would carry the astronauts safely back to Earth. He was also one of the Apollo mission’s “top troubleshooters,” according to NASA.

Owen Maynard

As for Maynard, Teitel said he is probably one of the most recognizable Canadians who worked for NASA at that time thanks to his contributions to the design of the small lunar lander.

“Owen Maynard began working on his own little concept for a lunar module, kind of a ‘landing bug’ as he called it, and that actually became the basis of the lunar module that went to the moon,” Teitel explained.

According to NASA, Maynard made the first “serious sketches” of the designs for the lunar module.

“Maynard's conception of the LM [lunar module] was used by STG [Space Task Group] to help sell the idea of Lunar Orbit Rendezvous around NASA,” a tribute to Maynard reads.

Houbolt’s LOR idea was eventually adopted by the rest of NASA for the Apollo mission thanks, in large part, to Chamberlain and Maynard’s early advocacy.

“Maynard was among the first at the Space Task Group to see the wisdom of using LOR to fly to the moon at a time when other methods were favoured,” a NASA tribute to Maynard reads.

Teitel said Maynard’s designs propelled him to the role of chief of the lunar module engineering office for the Apollo program in Houston. In 1964, he was promoted to chief of the systems engineering division for the Apollo program, making him the mission’s “chief engineer,” according to Teitel.

NASA described him as an “outstanding leader” of the Apollo program and one of Canada’s “great space flight pioneers.”

Bryan Erb

Another Canadian engineer who was invited to NASA’s Space Task Group after the dissolution of the Avro Arrow program was Bryan Erb from Calgary. He was an engineering aerodynamicist who worked on thermal analysis on the Avro aircraft.

Erb lent that expertise to the development of a heat shield for the Apollo spacecraft’s command module, which protected the astronauts from extreme heat as they travelled through the Earth’s atmosphere on their return home.

Because they weren’t able to exactly recreate the conditions the spacecraft would experience on the ground, Erb said he was tasked with coming up with a mathematical model to predict how the heat shield would perform. The first big test for his calculations came for the Apollo 8 mission.

“I was very, very happy when the heat shield performed as I had predicted it would,” he told CTVNews.ca during a telephone interview on Friday.

Following that success, Erb said he felt confident his heat shield would protect the astronauts on future missions, such as Apollo 11, where his designs were put to good use again.

Erb also developed the “barbecue” method for Apollo flights, which involved rotating the spacecraft on its horizontal axis to keep an even distribution of heat and exposure to solar radiation, according to his biography on the University of Alberta’s alumni website. He graduated from the university with a degree in civil engineering in 1952 before returning for a master’s degree in fluid mechanics.

Erb has also been recognized for his role in the management of a Lunar Receiving Laboratory where astronauts were quarantined and material from the moon was analyzed. He fondly remembers being concerned about the collection of those rocks on the day of the lunar landing.

“I had bought a coloured television for the first time and had a number of guests over and we were watching the landing and [Neil] Armstrong and [Buzz] Aldrin got out on the surface of the moon and started jumping around and having a great time playing, and I found myself shouting at the TV ‘Quit jumping around and pick up the damn rocks!’” he said with a laugh.

The aerodynamicist was also responsible for the first-world scale inventory of wheat using satellite data, for which he was awarded the NASA Exceptional Service medal.

Following his career at NASA, Erb joined the Canadian Space Agency in 1986 and represented Canadian interests at the Johnson Space Center.

Reflecting on his time at NASA on the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, Erb said he’s pleasantly surprised there’s still so much interest in the moon landing.

“It’s rather gratifying to see that so many people remember it. The public memory is rather short in many ways and they sort of view it as a good time and a good accomplishment,” he said. “I feel very blessed to have had a most interesting and challenging career.”

The Canadian contribution

In 2009, on the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, Hodge and Maynard were honoured by the Canadian Air & Space Museum for their contributions to the lunar landings.

“Most people are familiar with the Apollo 11 mission, when man first stepped on the moon back on July 20, 1969, but they don’t know of the instrumental role that Canadians have played,” the museum’s chairman at the time, Wayne Barrett, said in a release. “These people played pivotal roles in the technology breakthroughs that made safe manned spaceflight possible.”

Teitel said the Canadians’ involvement in early space exploration and the Apollo 11 mission shows that it took an international effort to land a man on the moon.

“Neil Armstrong made the point that there’s no flag on the Apollo 11 crest, there’s no language except for the name of the mission because the crew wanted it to be a mission for humanity,” she said.

“It really did take just the most brilliant men and women from all over the world to make this thing happen.”