TORONTO -- People’s Party of Canada Leader Maxime Bernier was directly challenged to defend his position on reducing immigration during Monday’s English-language debate, but his suggestions over immigrant integration don’t entirely add up.

Faced with a series of his own tweets in which he used the words “ghetto” and “tribes” to describe new immigrants to Canada, debate moderator and CTV News anchor Lisa LaFlamme pressed Bernier overhis concerns that immigrants bring “distrust.”

His response alluded to the fact that immigrants have difficulty integrating at current immigration levels, a suggestionthat both immigration data and experts prove mostly incorrect.

The claim

“We must have fewer immigrants in this country to be sure these people participate in this society,” Bernier said in his response.

“We don’t want our country to be like other countries in Europe where they have a huge difficulty integrating their immigrants.”

For context, Bernier has campaigned on promises to reduce immigration, saying the number of people allowed to enter the country as permanent residents should be cut in half to about 150,000 immigrants per year.

The analysis

There are several different factors to look at when it comes to issues of integration. When it comes to issues of social integration, immigrants to Canada seem to fare quite well.

According to Statistics Canada, 93 per cent of immigrants surveyed said they had a very strong or strong sense of belonging to Canada, compared to only three per cent who still felt strongly tied to their country of origin.

It’s worth noting that although this is the most recent data from Statistics Canada, it stems from a 2013 General Social Survey focusing on immigrants who landed between 1980 and 2012.

However, according to the 2016 Census, 93 per cent of immigrants reported knowing one or both of Canada’s official languages, an important factor in integration. Similarly, 85 per cent of eligible immigrants became Canadian citizens.

Canada’s immigration policies, both at the federal and provincial level, largely help immigrants with social integration, according to Avnish Nanda, a spokesperson for Everyone’s Canada, a non-profit organization that promotes multiculturalism in Canada.

Speaking to CTVNews.ca by phone from Edmonton, Nanda noted that Canada’s history of multicultural pockets plays a big role in social integration.

“One of the things that makes Canada so good is the notion of large ethnic enclaves,” Nanda said of neighbourhoods like Brampton, Ont. or Richmond, B.C., known for their multiculturalism.

“These pockets have a very significant impact on new arrivals to integrate into communities because they can learn from other generations.”

However, some have criticized the government for not doing more to assist with family integration, which experts say plays a large role in how immigrants fare both economically and socially.

“Different members of family units contribute to integration in terms of financial, emotional and cultural support,” Jamie Liew, associate professor at the University of Ottawa’s faculty of law, told CTVNews.ca by phone from Ottawa. “Grandparents and parents get a bad reputation, but there is data that shows those people can help better integration.”

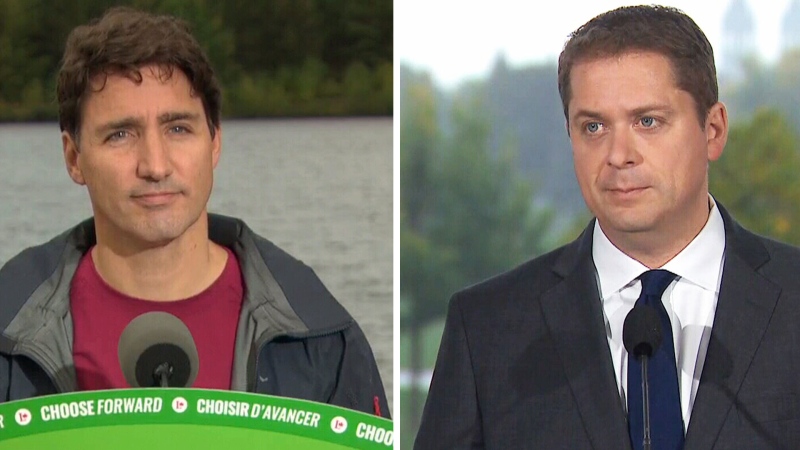

In 2018, the Liberal government under Justin Trudeau scrapped a controversial lottery system for reuniting immigrants with their parents and grandparents, increasing the cap of applications from 17,000 to 20,000.

The generational effect matters when it comes to economic integration, too.

“There is some evidence from Stats Can to show that there is an initial period during which newcomers, especially refugees, have difficulty with economic integration, but that is overcome by the next generation,” Christina Clark-Kazak, associate professor at the University of Ottawa’s school of public and international affairs, told CTVNews.ca by email.

“In fact, children of immigrants are proportionately more likely to complete university than children born in Canada.”

According to the Canadian Index for Measuring Integration (CIMI), immigrants with full-time jobs make an average of $54,699 per year, just below the national mean of $56,010. CIMI, which uses data from Statistics Canada, also notes that 81 percent of immigrants are employed full-time, compared to 79 per cent of non-immigrants.