A pair of University of Saskatchewan researchers have published a paper showing evidence that a large tsunami rolled over the prairies.

The duo, Brian Pratt and Colin Sproat had their work published in the November 2023 edition of a Sedimentary Geology— journal on published research and review papers in the field of sediment and rocks.

They say they’ve found the strongest evidence of a high energy event that occurred around 450 million years ago, in a place not known for its oceans.

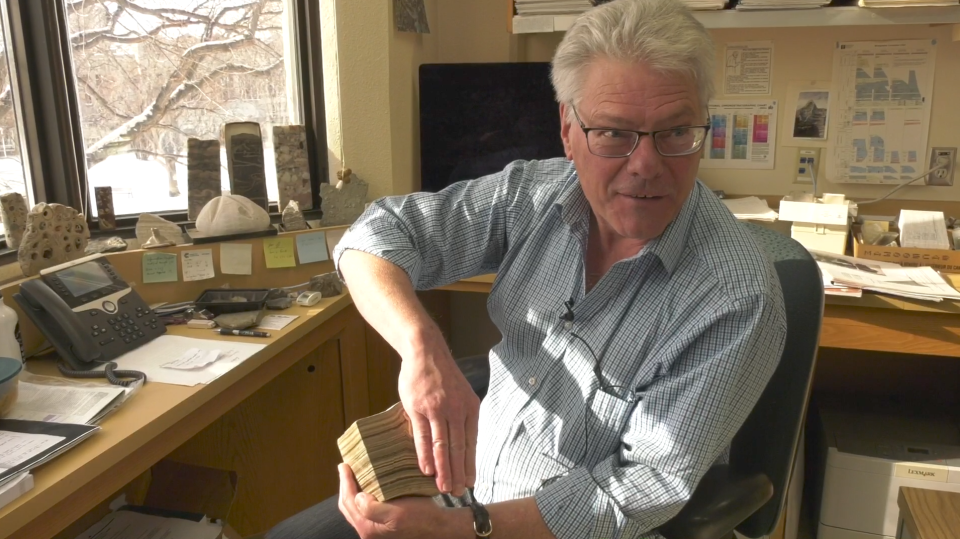

“Nobody expects to see them in these shallow inland seas which covered southern Saskatchewan and adjacent Manitoba,” said Brian Pratt, professor in the department of Geological Sciences at the University of Saskatchewan.

“So nobody even thinks about it. Even the textbooks don’t even mention it.”

The prairies used to be located close to the equator in the Ordovician period, covered by a shallow sea called the Williston Basin.

Pratt and Sproat were doing work near The Pas, Manitoba when they found distinctive layering in the exposed rock outcrop.

“One of these beds just stood out, it was just different,” Pratt told CTV News.

“When we worked out the characteristics and what kind of flow regime you would have, the only explanation we can come up with is a tsunami that swept across the northern part of the basin.”

By looking at the composition of the layers, they found the presence of clays in the rock suggesting it was dragged out to sea from inland. Pratt and Sproat conclude this is evidence of a high-energy event.

“These nodules that have been eroded out of the underlying muddy stuff, and then clay washed in,” said Pratt. “The clay has to come from the land surface, so that was really the evidence.”

It was widely accepted that large storms would have created these distinctive deposits. But since the Williston Basin was located near the equator, Pratt says it had to be something stronger.

“Something much stronger than normal processes,” he said. “And we were pretty close to the equator. Way back 450 million years ago, it was really a low-energy time. No hurricanes, no big storms, so we need some other process to draw this stuff out.”

While Pratt admits the idea is radical, he is confident this is a possible explanation.

“99 out of 100 people would have said, well, it's a storm deposit,” said Pratt. “And then we would say well, it doesn't look like one, it doesn't have the right features. That’s because a storm is a wave process, whereas this was a unidirectional flow off the land.”

The researchers plan to visit other sites in Canada to see if other ancient tsunamis revealed in the rock were a bigger part of Earth’s history than previously believed.