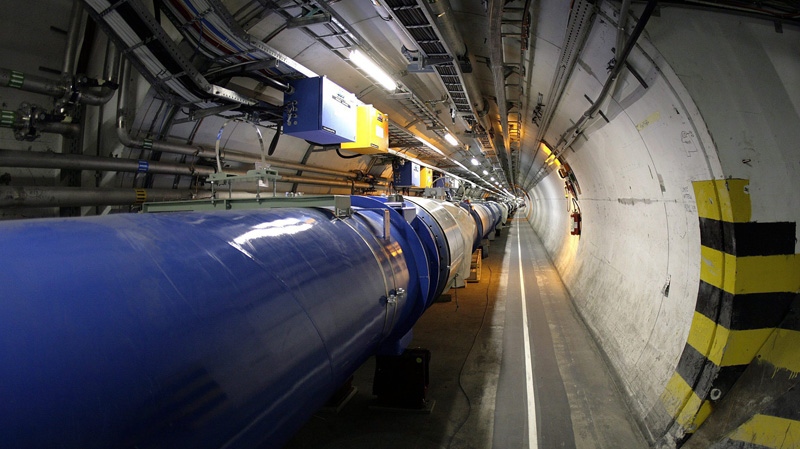

All that atom-smashing in Europe's $10 billion Large Hadron Collider has paid off in a big discovery that scientists say helps explain another mystery of the universe.

The head of the world's biggest atom-smasher -- the European Centre for Nuclear Research (CERN) on the Swiss-French border -- told a crowd of excited scientists Wednesday that researchers have discovered evidence consistent with theories of the subatomic building-clock popularly referred to as the "God particle."

"We have now found the missing cornerstone of particle physics," CERN director Rolf Heuer said during a presentation in Geneva.

"As a layman, I think we did it," he said. "We have a discovery. We have observed a new particle that is consistent with a Higgs boson."

Bosons are believed to be the basic building blocks of the universe, tiny elementary particles from which everything is made. The Higgs boson, named after the Scottish physicist Peter Higgs who was among the first to theorize about it in the 1960s, is seen as key to understanding why some particles have mass, while others do not.

According to the theory, there is an energy field that pervades the known universe, interacting with the quarks and electrons that make up the atomic building blocks of everything in it. Without the Higgs field, there would be no matter, and therefore no planets, or life as we know it.

Scientists have been hunting for a Higgs boson, because finding a particle of the pervasive energy field is the simplest way to prove the invisible field is actually out there.

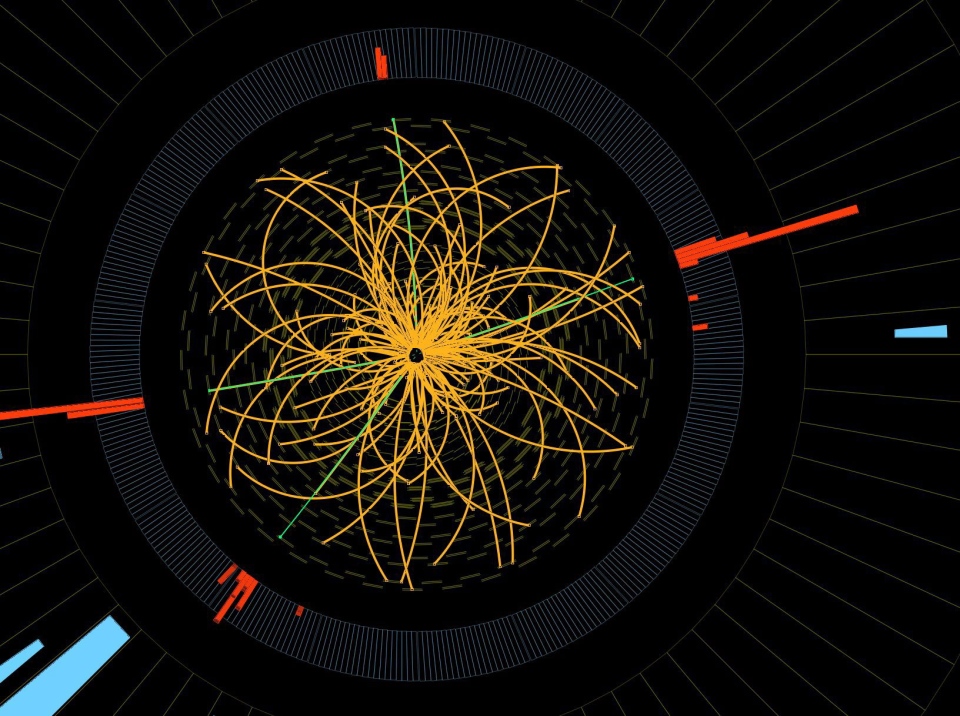

To find it, they’ve been smashing protons together -- more than 1,000 trillion times, in fact – trying to create a Higgs boson in the collision. In the rare times they produce one, it decays so quickly they have to sift through the atomic debris for evidence of the particles it decays into.

That's why, when asked whether the complicated findings presented Wednesday represent a "discovery," Heuer drew a distinction between what the experts have learned and what the average person should take away.

"As a layman, I think we have it. But as a scientist, I have to say, ‘What do we have?'" he said, explaining more research is needed to pin down exactly how it fits in with their theories.

Heuer's comments followed the presentation of findings by two independent teams that have been working at the underground research facility, both of which said they have "observed" a particle that could be the one they've been looking for, or at least a variation of it.

Joe Incandela, spokesperson for the 2,100-scientist CMS team, said it was too soon to say definitively whether their data pointing to the existence of a particle weighing in at 125.3 gigaelectronvolts (GeV) is the "standard model" Higgs. But whatever it is exactly, he said it's a big find.

"This boson is a very profound thing we have found. We're reaching into the fabric of the universe in a way we never have done before. We've kind of completed one particle's story," he said.

"Now, we're way out on the edge of exploration."

Fabiola Gianotti, spokesperson for the 3,000-strong ATLAS research team, also cautioned that their work -- which documents evidence of a similar, but slightly higher mass particle -- is far from complete.

The dream, she said, "is to find an ultimate theory that explains everything -- we are far from that."

But, based on the “sigma” scale particle physicists use to rank the certainty of their findings, the teams rated their results at the top of scale reserved for cases in which there's less than a one in a million chance of being wrong.

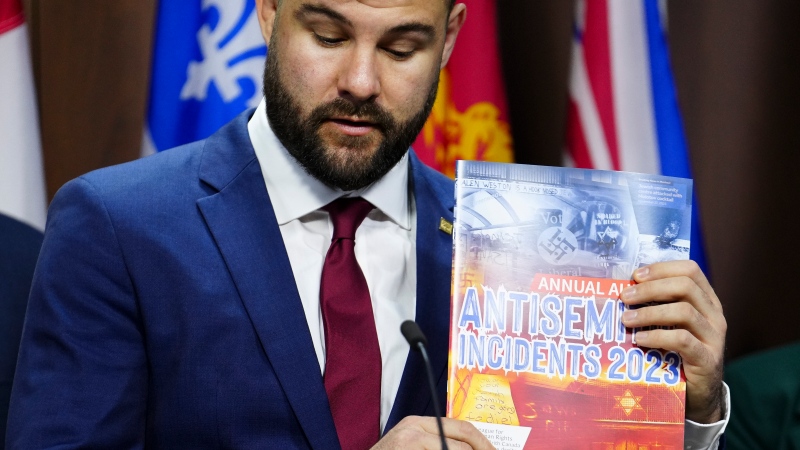

The headline-grabbing name "God particle" was popularized in the title of a book by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Leon Lederman, but is not favoured by researchers in the field.

The popular phrase goes a long way to capturing its significance, however, as scientists say the confirmation of a Higgs boson could unlock our understanding of the so-called dark matter and dark energy comprises the 96 per cent of the universe they believe is out there, but otherwise unobservable.

Chief correspondent for the scientific journal Nature Ivan Semeniuk told CTV's Canada AM that this latest discovery won't change any theories just yet. But it's a big deal because, until now, it has remained the final unproven element of the so-called "Standard Model" of physics.

The last discovery of an elementary particle was the top quark in 1995, he said.

"Since then, there's only been this last piece of the puzzle left to detect," Semeniuk said in an interview from Washington Wednesday morning.

"It's been a very elusive search, I mean the particle was first proposed in the 1960s and it's taken this long to detect it."

The significance of that long hunt and its recent breakthrough wasn't lost on the particle's namesake Wednesday.

On hand for the announcement in Geneva, the now 83-year-old Higgs agreed it was too soon to say whether the particles they've found line up with his original theories, but it is still "an incredible thing that it has happened in my lifetime."

Higgs added, "I never expected this to happen in my lifetime and shall be asking my family to put some champagne in the fridge."