Archeologists believe that beer and hallucinogenic drugs helped cement the rule ofthe ancient Peruvian Wari Empire, which ruled the highlands of Peru from 600 to 1000 AD.

In a study published in the journal Antiquity, archeologists posit that hallucinogenics from the vilca tree were added to beer during feasts, a communal use of drugs that reinforced Wari control by bonding at celebrations and making the leadership important as providers of the drugs.

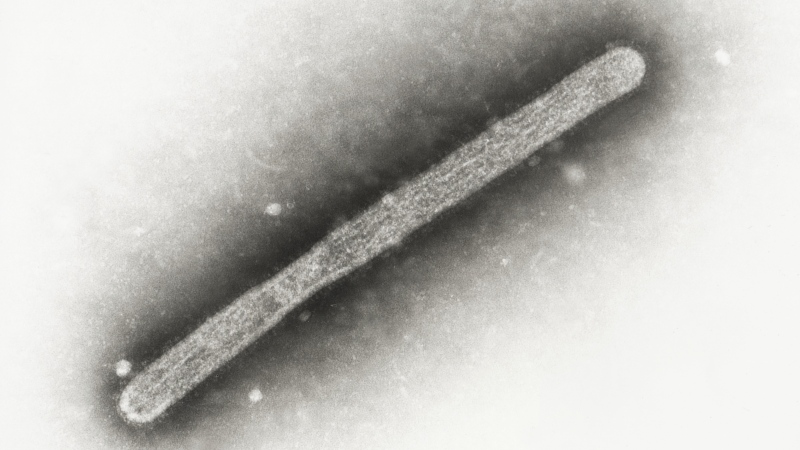

Botanical remains of vilca were found at the archeological site of the Wari outpost of Quilcapampa, Peru, which was established during the ninth century and occupied for decades.

Fieldwork led by the Royal Ontario Museum found over a million botanical remains, including the first seeds ever found from the hallucinogenic vilca tree found at a Wari site. The team also found evidence that “chicha,” a beer-like alcoholic beverage, was brewed from the molle tree in large quantities at the outpost.

Evidence from the site’s core, including ceramics and vilca seeds, suggests that chicha production and consumption occurred during feasts that were held for guests and the remains studied most likely came from a feast that was held near the end of Quilcapampa’s occupation. The study posits that finding the chicha, vilca and ceramics so close indicates that vilca was added to chicha to enhance the psychoactive effects.

Vilca has long been used in South America, evidenced in a 4,000 year-old pipe at the Inca Cueva site that was found with compounds from the plant inside, including the seeds. The study states that during the time of the Wari Empire, the neighbouring Tiwanaku used the drug extensively as well, through inhalation.

But the Wari site at Quilcapampa appears to show a new method of ingesting the substance. Whereas earlier use of vilca appeared to be exclusionary, with only a select few allowed to partake and in isolated settings, such as at the Chavin de Huantar site in Peru from the first millennium BC, where a limited number of priests or holy men may have consumed vilca in a powder form in enclosed galleries.

In contrast, the Wari outpost shows that vilca was incorporated into communal feasts hosted by the elites that “cemented social relationships and highlighted state hospitality,” the study says. The researchers suggest the more inclusive strategy may been integral in reinforcing political control.

“These individuals were able to offer memorable, collective psychotropic feasts, but ensured that they could not be independently replicated,” the study states, noting that the difficulty in obtaining and preparing vilca would grant the Wari who provided it special status.

The study posits that this new way of using vilca was a key development for politics in the region, noting that the later Inca Empire also followed the Wari style of communal drug use, though preferring group consumption of beer made from maize rather than vilca.