OTTAWA -- Appearing before parliamentarians, incoming Supreme Court justice Michelle O’Bonsawin said she hopes her unique perspective will allow her to make a "lasting contribution" as the first Indigenous person chosen to sit on Canada's top court.

"I would hope that this experience, both background, personal, and also my professional experience… is something that's unique to me, and would be beneficial to myself on the Court and hopefully to the Court as a whole," said O’Bonsawin on Wednesday.

After opening with a few lines in the Abenaki language she fielded two hours of questions from members of the House of Commons Justice and Human Rights Committee, the Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, as well as a Green Party MP about her career, experiences, her goals in the new role, and her perspective on the law.

Moderated by the University of Ottawa's vice-dean of the French common law program Alain Roussy, parliamentarians were advised to not ask her to comment on issues that may come before the Supreme Court, citing the need to maintain judicial impartiality.

O'Bonsawin spoke about her views on the intersection of mental health issues and the legal system, her extensive research into Gladue principles, and access to justice challenges.

"My experience has assisted me as a judge to review all cases with an open mind and sensitivity," she said.

On Aug. 19, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced O’Bonsawin's nomination, and the appointment was quickly celebrated as filling an important role at the highest level of the country's justice system.

An Abenaki member of the Odanak First Nation, in her application O'Bonsawin wrote about her experience as a First Nations' lawyer and said as a child in a working-class household, it was her "dream" to become a lawyer. She said Wednesday when she was selected for an interview for this position she felt like that young girl again.

O’Bonsawin spoke about the help she's received from mentors, and also offered some personal insight about her family and home life. She shared with parliamentarians that husband is an engineer and a lawyer, and they have two sons. At home she has three dogs, eight chickens, one gecko, and aspires to add a cat into the mix.

A number of questions were put to the justice about her being the first Indigenous person to be nominated to the Supreme Court, and O’Bonsawin said being the first isn’t always easy.

“You’re under a microscope at times, but I've learned that how to go about it is just to be hardworking, do the best that I can with my background and my experience, and to remain humble, listen well, be collegial with others,” said O’Bonsawin. She emphasized the last point given she’s 48-years-old and will have many years on the top court before reaching the mandatory retirement age of 75. “I’m in it for the long haul,” she said.

Wednesday’s hearing was part of a process the Liberals instituted in 2016 meant to increase transparency in the Supreme Court vacancy appointment process.

The search that ultimately led to O'Bonsawin's nomination began in early April when Trudeau launched the selection process to identify candidates, giving prospective applicants until May 13 to apply.

It was then the job of an independent advisory board to consider applications and submit a short list for consideration to the prime minister. The board said it received 12 applications and ultimately interviewed six candidates. Trudeau was given the shortlist in late June, months before naming O’Bonsawin as his Supreme Court pick.

The process is enacted each time a vacancy is looming. In this case, O’Bonsawin 's nomination is to fill the vacancy created by the upcoming Sept. 1 retirement of Supreme Court Justice Michael Moldaver after 11 years on the top court. A vote is not required to confirm her appointment.

CHANGES COULD INCREASE DIVERSITY: CHAIR

Ahead of hearing from O’Bonsawin, members of the House of Commons Justice and Human Rights Committee heard from chair of independent advisory board chair and former PEI premier Wade MacLauchlan and Justice Minister David Lametti about the selection process and her nomination.

During their Wednesday morning committee appearance, MacLauchlan said while the selection of O'Bonsawin—a fluent, bilingual Ontario judge becoming the first Indigenous person chosen to sit on Canada’s top court—is evidence the independent process is working, there could be improvements. He suggested changes to the process that could ensure more diverse candidates continue to put their names forward.

"If this were an ongoing conversation—as opposed to something that we scrambled to do just in the face of an imminent departure from the Court and the need to recruit a new candidate—I think it might be something that could broaden the scope of candidates," MacLauchlan said, referencing comments made by his predecessor in the role, former prime minister Kim Campbell. "I concur with these comments."

He also said the process could benefit by having more time for candidates to consider applying, and then for the board to assess the applications received.

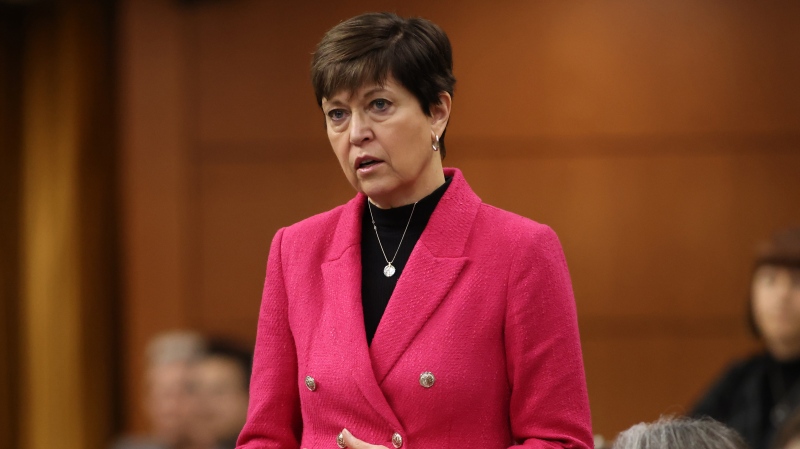

Justice Michelle O'Bonsawin participates a special meeting of the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, following her nomination to the Supreme Court of Canada, in Ottawa, on Wednesday, Aug. 24, 2022. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang

"The process involves considerable study, discernment, and consideration of many details in the space of approximately six weeks or even less… The work was done with diligence, collaboration, judgment, and that helped the process. That being said though, I think an additional week or two for the timeframe would be beneficial for future appointments to the Supreme Court," he said.

Given it may now be some time before the next appointment, MacLauchlan suggested it could be an opportunity for these changes to be made and begin outreach to potential future jurists well in advance.

"Quite a bit of getting the word out is not so much to give notice, but to set in motion networks of encouragement. Lawyers and jurists, who are highly qualified in a way that makes them contenders for appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada, are not in the habit of applying for a job. They may need an encouraging nudge from colleagues, they will need to talk it over at home to weigh family considerations, including what it means to move and relocate to Ottawa," MacLauchlan said.

Lametti touted the process on Wednesday, saying O’Bonsawin's appointment is an indication that it "produces nominations of exceptional judges who bring to the Court not just uncontested judicial excellence, but also a rich humanity and a deep understanding of the diversity of Canada."

"I'm confident she will serve Canadians exceptionally, upholding the Court's highest ideals, and guiding the evolution of Canada's laws," Lametti told the committee.

APPOINTMENT LAUDED AS AN INSPIRATION

O’Bonsawin has been a judge at Ontario’s Superior Court of Justice in Ottawa since 2017, and earlier this year, she successfully defended her PhD thesis on the application of Gladue principles, which are ways for courts to consider the experiences of Indigenous people when making sentencing decisions.

"It was a good thing that I'm a really organized woman," she told the committee.

The incoming justice has also been described as having expertise in mental health, human rights and employment law, stemming from her experience working as general counsel for the Royal Ottawa, a specialized mental health hospital in Ottawa, with the legal services at the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and as counsel for Canada Post.

When her nomination was announced, Indigenous leaders touted her appointment as an inspiration and one that will see the Supreme Court enriched by having a justice on its bench that can interpret Canadian laws through an Indigenous lens.

During the Wednesday morning hearing, NDP MP for Nunavut Lori Idlout said O'Bonsawin's appointment "opens up the opportunity for a pluralistic legal system to be established and recognized," and called on the federal government to ensure it is not a one-time move without further follow through when it comes to reconciliation in the justice system.

Other MPs and senators voiced optimism for the move being another step, following last year's appointment of Justice Mahmud Jamal, towards ensuring the Supreme Court of Canada reflects the population of Canadians.

"I wrote in my book after you finished your opening comments: 'So normal and so exceptional.' I think that those are the characteristics that have come through in your questions and responses, and I thank you for that," said Sen. Peter Harder during the afternoon session.

Ahead of O’Bonsawin’s remarks, Liberal MP for Nova Scotia Jaime Battiste called it "a great day."

"As someone who is a member of the Indigenous Bar Association for more than 20 years as a student, and then coming back as an Indigenous parliamentarian, I often heard the advocacy and the dream that someday we would see an Indigenous nominee to the Supreme Court of Canada," he said.

Responding to Battiste, Lametti said he agreed with how important it was for Indigenous people to see themselves "in what are quite frankly colonial institutions, and see their participation as a way of making those institutions better, and see this as a way of making Canadian law better."