Women typically perform more cognitive and emotional labour than men when it comes to managing household responsibilities, but experts say this so-called "worry work" has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and may have a lasting impact on gender equality if greater supports aren't made available to mothers.

Booking children's appointments, organizing playdates, creating the grocery shopping list for the week, worrying about your kids' grades and whether they have a clean face mask for school are all considered "worry work," according to Andrea O'Reilly, a women's studies professor at York University in Toronto.

O'Reilly told CTVNews.ca that "worry work," also known as "maternal thinking" or the "mother load," may seem minor, but these tasks can pile up to a point where they become overwhelming and impact a woman's mental health.

O'Reilly explained in a telephone interview that women have handled an "overwhelming majority" of the household responsibilities during the pandemic.

- Mental health care in Canada: Where to find help

- Newsletter sign-up: Get The COVID-19 Brief sent to your inbox

So why not just ask fathers to do more around the house?

While some families may delegate tasks between the mother and father to help with this, O'Reilly says it's actually more about remembering that these tasks need to get done, rather than who completes them.

"Delegation does not equality make. If it's the mother who's remembering that an appointment has to be made and then the father may do it, that's not equality," she said.

O'Reilly says the cognitive difference between women and men in remembering all of the practical elements of household responsibilities is "entrenched" in historic gender roles.

"We live in a culture that expects mothers to do it and if moms don't do it, they're blamed and shamed and regulated and judged in a way that men are not," she said.

O'Reilly said this is because society has linked the state of a woman's household to her worth as a person, so mothers fear they will be seen as "failures" if they don't do what is expected of them.

While O'Reilly acknowledges that "worry work" had been an issue prior to the pandemic, experts agree that COVID-19 has made it worse, as the closure of schools and daycares early on left many moms scrambling to take care of children while working from home.

THE 'MOTHER LOAD' IS HOLDING WOMEN BACK

Numerous studies have documented how the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected women. However, O'Reilly says women are struggling even more so now than compared to the start of the pandemic as they try to balance returning to the office and having children return to school.

O'Reilly said this has been difficult for women given that the situation in both of these settings can change quickly with little notice, adding again to a mother's load and impacting her career.

"Until we achieve gender equality in the home, we probably won't ever get gender equality outside of the home in the workplace because women are constantly being held back by doing the bulk of all those additional shifts of homemaking and housework and child rearing," O'Reilly said.

According to Statistics Canada, women accounted for 53.7 per cent of year-over-year employment losses from March 2020 to February 2021, with women of colour in particular facing higher unemployment than white women.

A May 2021 report from business consulting firm Deloitte forecast that Canada will face a major increase in mental illness that will last years past the end of the pandemic because of these job losses, with women again disproportionately affected.

Based on past experiences with mental health concerns following the 2008-2009 recession and the Fort McMurray wildfire, Deloitte estimates that the post-pandemic level of family doctor visits for mental health issues will be between 54 and 163 per cent higher than it was before 2020 – a range that equals between 6.3 million and 10.7 million Canadians.

According to a University of Calgary-led study, published May 2021 in peer-reviewed journal The Lancet Psychiatry, symptoms of anxiety and depression in mothers nearly doubled last year in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Between May and July of 2020, the study reported that symptoms of depression in Canadian mothers charted at 35 per cent, up from 19 per cent in the pre-COVID period documented between 2017 and 2019. Symptoms of anxiety, meanwhile, were at 31 per cent between May and July 2020, up from 18 per cent between 2017 and 2019.

THE MENTAL TOLL OF 'WORRY WORK'

Keetha Mercer, director of community initiatives and grants at the Canadian Women’s Foundation (CWF) in Toronto, told CTVNews.ca that the rise in "worry work" for women during the pandemic has increased feelings of depression, anxiety and burnout.

Mercer explained in a telephone interview that women who traditionally take on most of the caregiving responsibilities end up sacrificing themselves to keep their households afloat.

"Women are reported being even more burned out now than they were a year ago, and that burnout is escalating much faster among women than men because they're trying to work and care for children or elderly folk and managing the mental load of the family all at the same time," Mercer said.

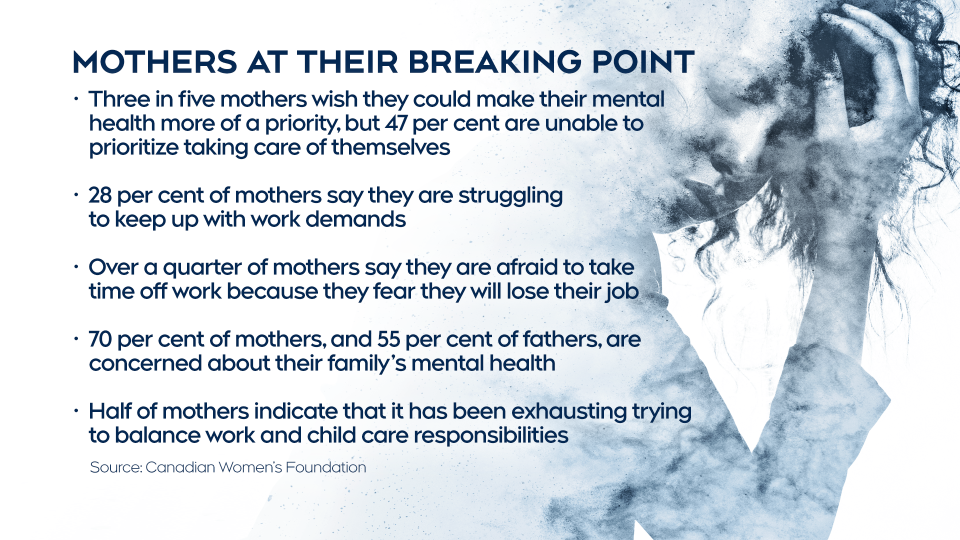

A July 2021 survey from the CWF revealed that almost half of mothers in Canada are "reaching their breaking point" amid the pandemic, with 46 per cent saying they are at their limit.

In addition, three in five mothers surveyed said they wish they could make their mental health more of a priority, but 47 per cent reported that they are unable to prioritize taking care of themselves amid household responsibilities.

Mercer said this has led to mothers carrying greater feelings of anxiety, isolation, anger, and sadness compared to men.

Mercer added that some mothers struggled more than others, especially those from racialized groups, newcomer communities, Indigenous women, and those with disabilities.

"The economic losses due the pandemic has fallen really heavily on women, and most dramatically on those living on low income who've experienced the intersecting inequalities of race, class, education and immigration status," she explained.

Because BIPOC communities have faced a greater risk of COVID-19 infection and death, experts say increases in mental health concerns for women in these communities has been worse.

Mercer said establishing universal childcare and better income supports, including paid sick leave, is necessary if governing bodies and employers want women to be able to return to the workforce.

"When women thrive -- when half of our population thrives --everybody thrives. Women disproportionately take care of the home, and this will ensure that the children, that elders, their partners also thrive," Mercer said.