Roy Baird was 78 years old when he was first diagnosed with bladder cancer after finding blood in his urine. After two-and-a-half years of treatment, all seemed well — but then it returned with a vengeance.

It’s a common story with what one doctor calls “the sticky cancer.”

“When you get diagnosed, there's a 60 to 70 per cent chance that the cancer can come back in the early stages,” Dr. Ramy Saleh, medical oncologist at McGill University Health Centre and an expert on bladder cancer, told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview.

“It can keep coming back and back and back again.”

But although bladder cancer is the fifth most common cancer in Canada, there’s a shocking lack of awareness surrounding whom it affects the most and what the most common risk factor is: smoking.

Receiving a diagnosis for bladder cancer was “a bit of a shock” for Baird, he admitted.

Naturally, he had a lot of questions for his doctor, the biggest being, “How does someone get cancer on their bladder in the first place?”

“He said they really don’t know,” Baird told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview. “But one of the main factors can be cigarette smoking.”

Baird had a history of smoking but hadn’t touched a cigarette since 1991. He said he’d never heard of smoking being a risk factor for bladder cancer before, only that it could be one for lung cancer.

The statistics for bladder cancer show that more than 75 per cent of those being diagnosed with this cancer in Canada are men.

But the most common denominator isn’t gender, it’s age and smoking, Saleh said.

“Ninety per cent of the cancer is in adults above the age of 50,” he said. “Almost all of them had either history of smoking, or they are still smokers. Those are the highest things.”

It’s still unclear why men are diagnosed with bladder cancer in much higher numbers than women. Saleh said part of this may be due to the smoking risk factor, and that perhaps more men are smokers, but he said he wasn’t sure.

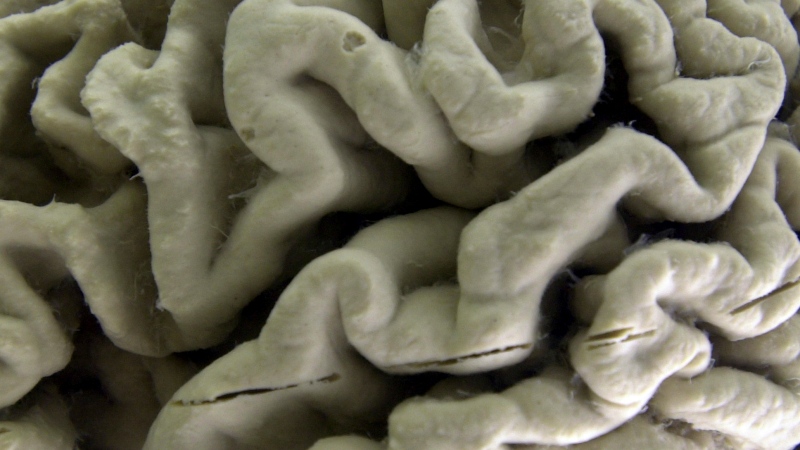

It’s no surprise that smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer — the respiratory system is very engaged when it comes to smoking. But the mechanisms behind why it’s such a big risk factor for bladder cancer are less clear, aside from the fact that smoking, in general, is associated with a myriad of detrimental health impacts.

“We think that smoking can cause some DNA damage in the cells,” Saleh said. “But to know the exact biology, we don’t really have that much of an understanding.”

May is Bladder Cancer Awareness Month in Canada, but that’s not something Saleh expects most people to know. There’s little awareness of the realities of bladder cancer, he said, particularly the treatment process, which can be harrowing, especially since this cancer has a tendency to come back.

“Not only (is) it the fifth most common cancer — around, I think, 12,000 people get diagnosed per year alone — but it is actually the most expensive cancers to treat (out of) all of the cancers combined,” he said.

WHAT MAKES THE ‘STICKY CANCER’ SO DIFFICULT

Experts still aren’t sure why bladder cancer has such a high rate of returning, Saleh said, but data has shown that when patients have non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, the chances are very high it will come back in the future.

"So the patients have to be very informed about that, they have to maintain their relationship with their urologist,” Saleh said. “You need to make sure they get their cystoscopies, which is an invasive procedure, done frequently to ensure that it doesn't come back, and if it does, they can catch it quite early before it spreads around.”

A cystoscopy is when a camera is inserted up into the bladder via the urethra to look around and ensure that the cancer hasn’t spread. Patients are given local anesthetic and are awake during the process, which takes only a few minutes.

While something like a colonoscopy to keep an eye on colon cancer is only done every five years or so, surveillance cystoscopies are performed far more regularly.

“Sometimes it can be done even once every three to four months,” Saleh said. “Unfortunately, it is the best way of seeing inside the bladder and making sure that if you have a lesion or if you have a small tumor that it's dealt with quite quickly.”

This three month schedule lasts for around two years for patients recovering from high-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, according to Dr. Jeffrey Spodek, chief of urology at the Scarborough Health Network. They will then generally receive surveillance cystoscopies every six months for another two years and then annually after that, all to ensure the cancer doesn’t return.

“It is an intense follow up,” he told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview Thursday. “But the reason for that is that there are high, high recurrence rates, so high chances that they come back, and we want to diagnose that early so we can treat it.”

The frequency is one of the drivers behind why bladder cancer is so expensive, according to Saleh.

“You need a urologist, you need to get your (local) anesthesia, you need to actually have a nurse with you in order for the urologist to be able to do the procedure,” he said. “You have to do all of this inside a hospital setting. And that's why it ramps up the cost.”

When bladder cancer is detected through a cystoscopy, patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer will receive a trans urethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT), to “scrape it out, remove it, and biopsy it,” Spodek said.

“If it's non-muscle invasive, but it comes back, then they have another TURBT. And then if it's muscle invasive, the treatment is very different. It's surgery to remove the bladder, it's called a radical cystectomy. That's option one and option two, in that situation, is radiation and chemotherapy. And then for metastatic bladder cancer, we usually do not do a TURBT unless the patient is bleeding, then we do, otherwise, it's chemotherapy.”

Unlike a cystoscopy, patients are put under for a TURBT, which can last around 30 minutes on average, and will then need to recover in the post-anesthesia recovery unit.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Blood in the urine is the most common and obvious symptom of bladder cancer, but other symptoms can include frequent urination or urgent urination that occurs in the absence of a urinary tract infection.

Prognosis depends strongly on the type: there’s bladder cancer that has entered the muscle of the bladder, cancer that has not entered the muscle, and finally metastatic bladder cancer, which is cancer that is spreading actively.

When bladder cancer is caught early, before actively spreading to other regions of the body, it is very treatable. But around 10 to 15 per cent of people diagnosed with cancer have metastatic disease, Saleh said.

“The five-year survival rate (for metastatic bladder cancer) is around five per cent,” he said.

Until a person has symptoms that prompt a cystoscopy, there’s no real way to screen for bladder cancer. There are no readily available blood tests or tests equivalent to mammograms, for example, for bladder cancer, although researchers have been working to develop a simple urine test to detect it before there is traces of blood in the urine.

The lack of early screening options makes it all the more important to contact a doctor to get access to a urologist immediately if you are above the age of 50 and notice blood in your urine, Saleh said.

It was Baird’s doctor who first noticed that he had blood in his urine and prompted the tests to receive his diagnosis in 2018.

Over the next two-and-a-half years, he received something called BCG treatment, the standard treatment for early bladder cancer, in which a liquid drug is delivered directly to the bladder through a catheter.

He also underwent four TURBT operations to remove the cancerous tissue.

Finally, Baird said, his doctor did another cystoscopy and told him they wouldn’t need to check again for a year, because “everything is beautiful.”

For the next six months, he was under the impression that his bladder cancer was gone. But during a CT scan to investigate his kidneys, a tumour was found on one of his ureters — thin tubes that travel from the kidney to the bladder.

An oncologist told him that if they didn’t do anything to address the tumour, Baird would be dead within six months to a year.

Last year, he began chemotherapy for the bladder cancer, which he underwent for three months, shrinking the tumour by around 40 per cent. At that point, doctors decided to shift to immunotherapy treatment, which Baird is still receiving.

“I have a treatment every two weeks,” he said. “So anyways, he seems to be happy with all the blood tests and everything looks stable.”

Immunotherapy is less invasive than chemotherapy

“Chemo sort of knocks it out of you a bit,” he said. “Whereas this is not — you get a bit tired, yes, maybe a little bit of a backache, but nothing like the other stuff.”

It’s also relatively new, part of a wave of treatment options being researched, trialled and entered into medical care.

“One thing I think people should know is that there is truly a lot of revolutionary medications that are coming in,” Saleh said. “I think there's an explosion of drug discovery in bladder cancer. Patients before, when they used to have metastatic disease five years ago, they did not have a lot of options at their disposal.”

“But recently, over the last five years, we've seen a lot of new medications come into play that offer patients a better quality of life and longer survival rates. I think this is important for people not to think like, ‘Oh, I have metastatic bladder cancer, this is game over.’ We're starting to see people live much, much longer than before, and even with a better lifestyle.”

He said that immunotherapy produces a better and more durable response in patients.

“And recently, over the last year-and-a-half, the government started approving what we call the antibody drug conjugate, also known as ADCs,” he added. "And those also are becoming more important than chemotherapy in metastatic disease, both of them.”

Immunotherapy works by stimulating the immune system to understand how to fight cancer. ADCs work as a delivery system to directly target the bladder cancer cells and kill them, he said.

“Those are more technologically advanced, I would say, than chemotherapy that goes into your system and kills the good and the bad, whatever it's facing in front of it.”

ADVICE FOR PATIENTS

Baird, who is now 83 years old, says he’s still got a positive attitude about his ongoing fight with bladder cancer.

“I've always been a positive person and this did not diminish it in any way. I'm still positive,” he said.

He wants to share his experience with bladder cancer in the hopes of generating more awareness, adding that he frequently sees campaigns for breast cancer and prostate cancer, but rarely any talk surrounding bladder cancer.

“I think they should do (an) equal amount of promoting (awareness) as the other two because it is becoming more and more prevalent now, bladder cancer,” he said. “Especially in men.”

Spodek said it’s good that the word is starting to get out now about smoking being a major risk factor for bladder cancer, noting that he’s seen awareness campaigns as well as warnings popping up on cigarette packaging.

Smoking is dangerous even if you’ve already developed bladder cancer, he added.

“We recommend that all patients stop smoking, even if they're diagnosed with bladder cancer, because the cancer can come back not just in the bladder, but also in the ureters and the lining of the kidney,” he said. “It’s recommended that everybody stop smoking to decrease the change of it recurring.”

Baird’s advice for newly diagnosed patients is to connect with patient support resources, something he said has been invaluable to him and his family.

“My wife and I, we both go to a cancer wellness centre because she's a caregiver – and doing a wonderful job, I might add,” he said. “And they’re very helpful.”

He and his wife have been together for 57 years.

“Having family helping you out is important too,” he said. “I guess that's for everyone, not just bladder cancer patients, but it helps. It helps to have that support.”

His other takeaway? Make sure you get a good idea of the realities of long-term treatment that come with this type of cancer.

“You've got to plan long term as, like I mentioned, two years, five years, whatever, of treatment,” he said. “Once you've been diagnosed with bladder cancer, you need to think about managing the disease in the long run. This type of cancer often requires a long-term treatment beyond the initial chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Have the conversation with the doctor.”

The complexities of bladder cancer diagnosis and treatment are exacerbated by understaffing and other strains on the health-care system, Saleh noted. He hopes that there will be more support in the future to help combat this — both for the patients’ sakes and the sake of an overwhelmed health-care system.

“The earlier we catch it, the better for everyone, especially the patients,” he said “Definitely if we have a better structure with better resources that will definitely lower the strain on cystoscopies and access to urologists, that's for sure.”

Correction:

This story has been updated to better describe the process of cystoscopies. A previous version incorrectly stated that they require time for patients in the post-anesthesia recovery unit.