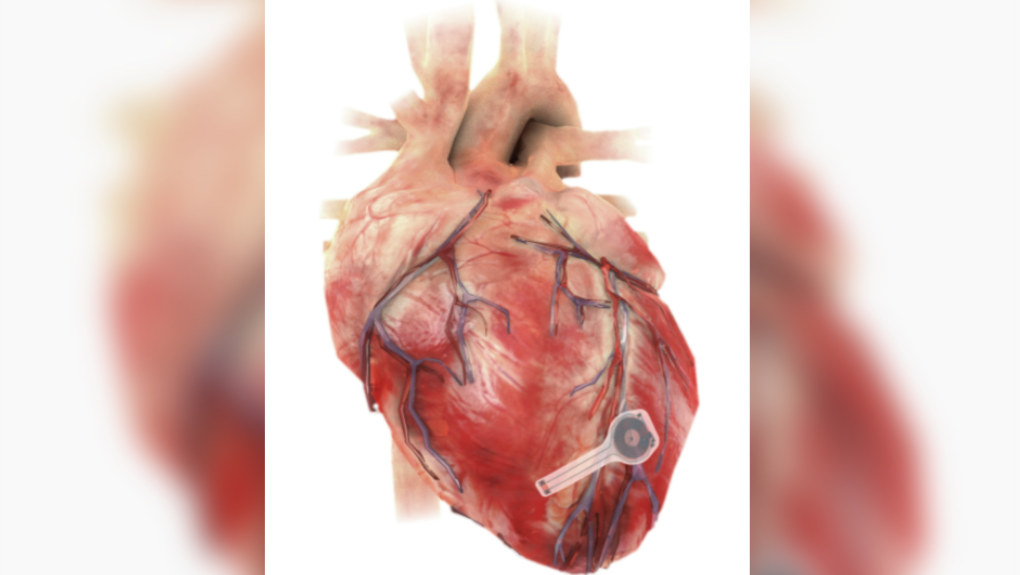

TORONTO -- Researchers at Northwestern and George Washington University in the U.S. have developed a medical first – a temporary pacemaker that is wireless, battery-free, fully implantable and dissolves after it is no longer needed.

The device, described as “thin, flexible and lightweight” could be implanted in patients who need temporary pacing after cardiac surgery or while waiting for a permanent pacemaker to be installed, according a news release.

All components of the pacemaker are “biocompatible,” meaning they will naturally absorb into the body’s biofluids over the course of five to seven weeks without the need for surgical extraction like a standard pacemaker device.

A study published Monday in the journal Natural Biotechnology details the device’s effectiveness in a range of large and small animals, including mice, rats, rabbits, dogs and human cardiac models.

“Hardware placed in or near the heart creates risks for infection and other complications,” said Northwestern’s John Rogers, who led the device’s development, in the release. “Our wireless, transient pacemakers overcome key disadvantages of traditional temporary devices by eliminating the need for percutaneous leads for surgical extraction procedures — thereby offering the potential for reduced costs and improved outcomes in patient care. This unusual type of device could represent the future of temporary pacing technology.”

The new device harvests energy from external sources using “near-field communication protocols,” the same type of technology used in smartphones for electronic payments. This way patients no longer have wire leads extruding from their bodies, which can become infected or enveloped by scar tissue.

If a patient needs temporary pacing after open heart surgery, the current standard is for surgeons to sew on a pacemaker’s electrodes onto the heart’s muscle during the operation. The device has leads or wires that exit from the front of a patient’s chest that connect to an external box that delivers a standardized current to regulate the heart’s rhythm. When the pacemaker is no longer needed, it must be surgically removed.

“Sometimes patients only need pacemakers temporarily, perhaps after an open heart surgery, heart attack or drug overdose,” said study co-lead and cardiologist Dr. Rishi Arora in the release. “After the patient’s heart is stabilized, we can remove the pacemaker. The current standard of care involves inserting a wire, which stays in place for three to seven days. These have potential to become infected or dislodged.”

The new device has no leads and is only 250 microns thick and weighs less than half a gram, according to the study. A strand of human hair, by contrast, is about 70 microns.

The researchers hope to continue their study and build up to human trials as well as exploring expanded methods for their device to be implanted through a vein in the arm or leg without open heart surgery.