COVID-19 hospitalizations are on the rise across Canada as a wave of autumn infections sweeps the population, according to recent data released by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

The latest numbers are nothing to panic over, infectious diseases experts say, but they can't be ignored either, especially with so many hospitals in the country already operating at or near capacity.

"I don't think there's anything unexpected in the sense that … we're going to see a rise in COVID-19 in the community as the summer turned to fall, just as we've seen every year since COVID emerged," Dr. Isaac Bogoch, clinician investigator at the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute, told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview on Monday.

"So then we're obviously seeing a rise in cases, and that's reflected in a rise in hospitalizations."

Canada recorded a total of 10,218 new COVID-19 cases from Oct. 1 to 7.

As of Oct. 10, COVID-19 patients occupied 3,797 hospital beds across the country — the highest occupancy rate since last winter.

Because testing practices, data sources and reporting to PHAC are not consistent from one province or public health unit to the next, the agency warned the data could be incomplete.

This is one of the reasons why Bogoch says hospitalization numbers need to be taken with a grain of salt and contextualized alongside other data.

"There's no one metric that tells the whole story. You've got to use all of the metrics available to you, contextualize them appropriately to paint an accurate picture of what's happening," Bogoch said.

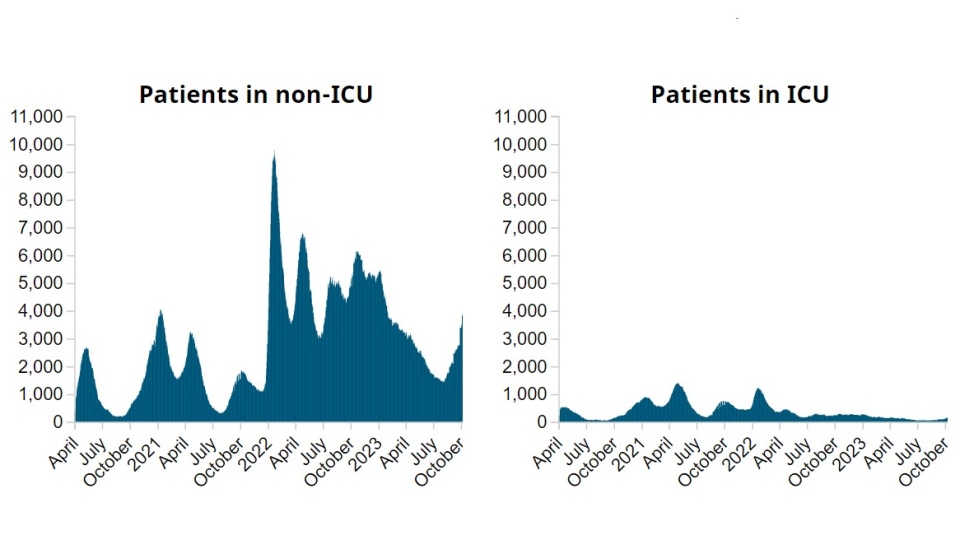

"If you look at the ratio of patients admitted to the ICU versus patients admitted to the wards, that's a helpful metric of looking at the severity of various of COVID waves."

PHAC's latest data, for example, reveals that patients in non-ICU beds comprise most of the latest increase in nation-wide hospitalizations, while both the number of COVID-19 patients in ICU and those receiving mechanical ventilation rose modestly, meaning fewer people are severely ill from the virus.

Bogoch treats COVID-19 patients in addition to publishing research on infectious diseases. He said hospitalization data can also be inflated by cases where a positive COVID-19 test is incidental to the primary reason a patient was hospitalized.

Bogoch treats COVID-19 patients in addition to publishing research on infectious diseases. He said hospitalization data can also be inflated by cases where a positive COVID-19 test is incidental to the primary reason a patient was hospitalized.

For example, an elderly patient admitted for injuries sustained in a fall that took place a month after a COVID-19 infection might be included in that hospital's tally of COVID-19 admissions, even if they were not actively suffering from symptoms of an infection at the time of admission.

"When you look at COVID related hospitalizations, there are some that are included in there that probably shouldn't be," Bogoch said.

"COVID does bring a lot of people into hospital for reasons beyond respiratory. But in addition to that, we just know there's a lot of incidental admission to the hospital. And as someone who admits people to hospital regularly, it's not always clear cut."

'COMPLETELY FLAT-FOOTED'

None of this means Canadians should be complacent about COVID-19 this fall, say both Bogoch and Dr. Michael Curry, clinical professor of emergency medicine at the University of British Columbia.

Each wave of COVID-19 infections and subsequent hospitalizations — no matter how small, relative to previous waves — tests the limits of understaffed hospital and primary care systems across the country.

"COVID is not even remotely close now, even with that rise in hospitalizations, to what we saw in 2020 and 2021," Bogoch said. "But it's also not nothing. It's still an additional pressure on an already stretched health-care system. And that's why it's challenging and it's going to continue to be challenging for the years ahead."

Curry works at Delta Hospital in Delta, B.C., and believes part of the problem is that hospitals often operate with just enough capacity to meet demand in normal conditions, with little or none to spare. In his time at Delta, he said the hospital has never reported a capacity level below 90 per cent. For the past 18 months, he said, that number has hovered around 115 per cent.

"Particularly in Canada, compared to a lot of other countries in the world, we run our hospitals on a just-enough model," Curry told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview on Monday. "We have no excess capacity. So we have barely enough to get by in usual times, which leaves us completely flat-footed during extraordinary times."

When hospitals find themselves understaffed in times of increased demand, one of the ways they respond is by temporarily closing emergency rooms. This year alone, CTV News has found more than 1,284 instances where a hospital emergency unit, usually in a rural community, has been shut down for hours or days.

"There's been a number of small- and medium-sized hospitals closing their emergency departments due to staffing shortages," Curry said. "This is a countrywide phenomenon."

Knowing hospitals across the country struggle to meet demand every time COVID-19 cases rise and that — however small the number — people are still dying due to the coronavirus, Curry and Bogoch said individuals should continue to do anything they can to help limit the spread of COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses.

That includes keeping up to date with COVID-19 and flu vaccines, staying home when sick, wearing a mask in crowded settings and maintaining proper hand hygiene.

– With files from CTV National News Medical Correspondent Avis Favaro