SASKATOON -- Amid calls for accountability and compensation for child deaths at residential schools, lawyers say it’s unlikely Indigenous families will receive it from the government any time soon, especially since there has been no national inquiry yet into the deaths.

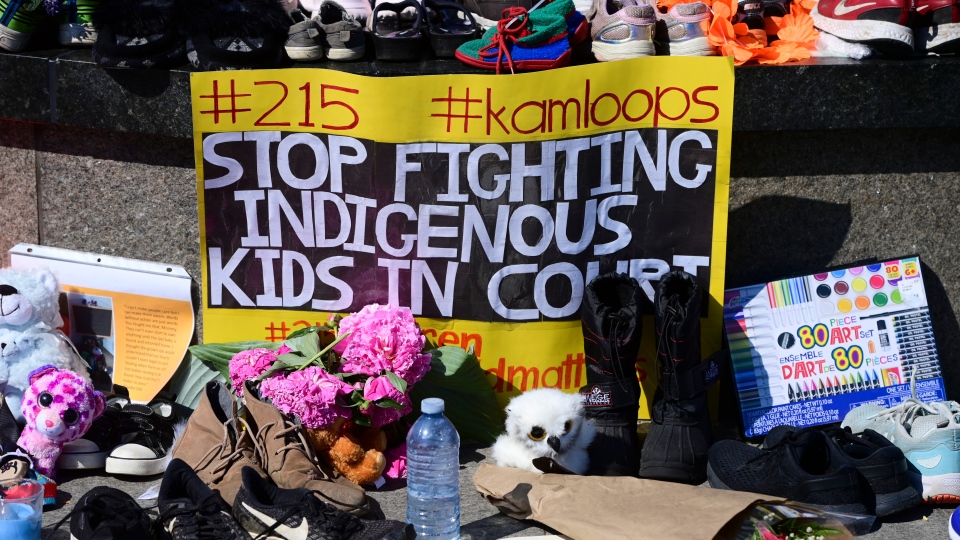

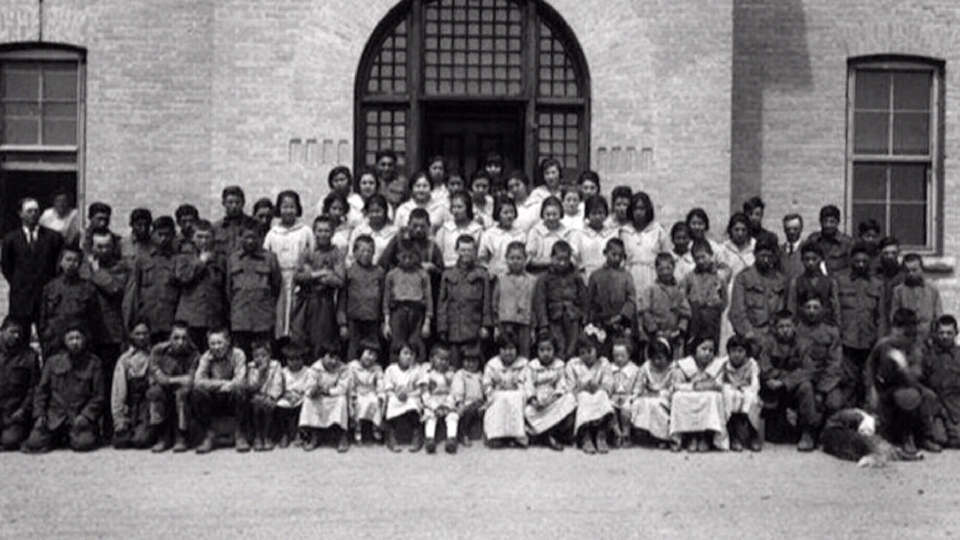

The horrific discovery of the remains of 215 Indigenous children at the site of a residential school in Kamloops, B.C. has prompted demands that all former school sites be searched for hidden graves – something Saskatchewan recently announced it was doing.

The United Nations Human Rights Office, along with many commenters on social media, are renewing calls for government compensation for those whose family members went to these schools and never came back. Lawyers say that compensation is unlikely, at least for now.

- READ MORE: Indigenous crisis support: Where to find help

- How to support survivors of residential schools

“I think it shouldn’t be done as a legal obligation, but a moral obligation,” Winnipeg-based lawyer Bill Percy told CTVNews.ca over the phone on Tuesday. His past cases have involved sexual abuse victims and Indigenous law.

“There should be political will. I mean, it's clearly wrong what has happened to these people,” he said, noting that the federal government has apologized for the schools and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) determined widespread abuse in the residential school system.

But he stressed, “I don’t see financial compensation being on the lips of government people so far.”

However, if the government wanted to, Percy said it could set up a system to provide compensation in a way that “makes sense.” In 2007, after years-long legal battling, the government set up a multi-billion dollar agreement to give direct payments to tens of thousands of survivors of residential schools, but it’s since ended. Its focus did not include families whose children had died at the schools.

Percy urged officials to set up a similar compassionate program for the families to seek restitution for their late loved ones, one that wouldn’t require them to provide mounds of evidence to prove the deaths were directly the fault of administrators -- as if it were a standard civil class-action lawsuit.

And although Eleanore Sunchild, a Cree lawyer and Indigenous advocate, said “it’d be great” if the government did that, she’s not holding her breath.

“It's not going to happen anytime soon… not with current ways the Canadian government handles Indigenous issues and historical files,” she told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview on Tuesday.

As for whether the government is even considering implementing a compensation scheme, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) didn’t respond to CTVNews.ca’s requests for comment by the time of publication.

On Wednesday, however, the federal government did reveal it was ready to distribute $27 million in pre-announced funding to assist Indigenous communities in locating and memorializing children who died at residential schools. The money was earmarked in the 2019 federal budget, part of a $33.8-million commitment to be spent over three years to fund the National Residential School Student Death Register and to help “establish and maintain an online registry of known residential school cemeteries.”

'A WHOLE HISTORY HAS TO COME OUT'

Sunchild said that it is far too early to imagine the government setting up compensation funds without a full inquiry into the deaths at all residential schools. The inquiry would have to include testimonies from survivors, living administrators, and access to sealed historical documents.

Investigating how the children died -- whether by neglect, abuse, or disease -- would not only be meaningful for the families, she said, but it’d be essential in compelling the government to even consider compensation.

On Wednesday, the United Nations Human Rights Office echoed many families and advocates in calling on all levels of Canadian governments to investigate the deaths of Indigenous children at residential schools.

But Sunchild warned that another huge hurdle to compensation and inquiries is resistance from the Catholic Church, who administrated many of the schools, as did the Anglican Church. She said they would need to be forthright in providing crucial ledgers and public documents – and lawyers said voluntary openness was not the case during the TRC inquiries in the early 2010s.

“There's a whole history that has to come out. And all of the parties involved -- who are holding Indian residential school records and the records of the missing children -- they need to participate.”

ARE THERE ROADMAPS FROM PAST SETTLEMENTS?

All of the lawyers CTVNews.ca reached out to pointed to the need for a concerted effort from the government to attempt to give some form of restitution.

Lawyers said the last such effort was during the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. Set up in 2007, it served as a multi-billion-dollar fund for living survivors and abuse victims and still remains one of the largest class-action settlements in Canadian history.

It took years of legal haggling to bring to the table representatives of former students, the Assembly of First Nations and other Indigenous organizations, involved churches, and the federal government.

But nearly all of the 80,000 eligible former students and tens of thousands of abuse victims received payouts for the trauma they endured.

“It was a process that was easier than ordinary litigation because a lot of the expenses were borne by Canada and it was a non-adversarial process,” Montreal-based lawyer David Schulze, whose firm specializes in Indigenous law, told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview.

Wrongful deaths weren’t grounds for compensation in that agreement, and those claiming compensation were unable to file future lawsuits against parties involved, including the church and the government.

But all three lawyers CTVNews.ca spoke to said this multi-part agreement could serve as a loose template for a future compensation agreement for claims of wrongful death. Still, all of them stressed that the framework at the time was far from perfect.

The claims system was open to abuse, with private lawyers being able to charge their clients high fees. And before an additional legal agreement was reached in 2016, students in Newfoundland and Labrador were initially left out of compensation packages because Canada argued it did not establish or operate residential schools in that province -- Newfoundland wasn’t a part of the country when the schools opened, but it did help run schools after the province joined Canada in 1949.

MORE HURDLES TO GETTING COMPENSATION?

Some First Nations have suggested that all residential schools immediately be treated as crime scenes. While the TRC found that the residential school system amounted to cultural genocide, and some individual acts within the schools have been treated as crimes, no charges have been laid in connection with the system as a whole, or with any undocumented deaths.

"The perpetrators haven't been brought to justice," Pam Palmater, the chair in Indigenous governance at Ryerson University in Toronto, said Tuesday on CTV's Your Morning.

Percy noted that bringing individual or class-action civil lawsuits against living school administrators for wrongful deaths isn’t impossible, but it would be a huge challenge for a number of reasons: primarily because it would be on the plaintiffs to prove a cause of death.

This is amplified by a lack of witnesses who could provide evidence or testimony, or having living relatives willing to invest time and potentially re-traumatize themselves to partake in legal proceedings.

Percy noted if there was a potential class-action litigation from families now, he expected they’d face barriers similar to the ones he’s facing now with his current litigation for living survivors of day schools.

Last year, after years of legal battles, the government opened up applications for day school survivors to apply for compensation, a group that was excluded from various parts of the 2007 compensation payouts. Day schools were institutions where thousands of Indigenous students were forced to go to but could leave at the end of the day.

They can receive a range of compensation between $10,000 and $200,000, based on abuse suffered.

But Percy and Schulze said the claims process so far is problematic and adversarial. And they said it’s led to litigation against the federal government.

The lawyers say the government is being stricter with compensation criteria for the day school survivors. For example, Schulze explained that if someone filed a claim but wanted to modify the level of compensation they are seeking, they’re unable to add more details after the fact.

This might occur as survivors become more comfortable in disclosing more details.

So lawyers filed a motion to change the process back to an earlier method, which did allow for these types of modifications. The Federal Court has set a hearing in July in regards to this aspect, which Schulze and Percy say indicates that the government doesn’t intend to consent to the motion.

All three lawyers also said that if the government is combative when it comes to day schools lawsuits, they can only imagine how much tougher it will be for families whose children died at residential schools.

With files from CTVNews.ca’s Rachel Aiello and Ryan Flanagan

Edited by CTVNews.ca's Sonja Puzic and Adam Ward

If you are a former residential school student in distress, or have been affected by the residential school system and need help, you can contact the 24-hour Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419

Additional mental-health support and resources for Indigenous people are available here.