If millennials weren’t already feeling the pressures of high inflation and the soaring cost of living in Canada, a new study shows millennial renters will have to save over 50 per cent more for retirement than millennials who own a home.

According to the report by Mercer Canada, a global consultancy firm, millennials who rent will have to set aside eight times their salary to save enough to retire at 68 years old, whereas millennials who own their home only need to save 5.25 times their salary to be able to retire three years earlier, at 65.

In February, the average price of a home sold in Canada was $662,437.

Homeowners in retirement do not have the same cost of living as renters do, the report notes.

“Homeownership also gives retirees flexibility, as retirees who downsize may be able to access a significant amount of money. Renters, conversely, must pay rent every month or face eviction — whether they are 25 years old or 85 years old,” the report said.

Mercer Canada based its report on data and analytics from proprietary Mercer databases and tools. The report assumes the millennial starts saving for retirement at the age of 25, with a starting salary of $60,000, and contributes 10 per cent every year through a workplace savings program and invests that in a balanced fund.

According to data from the Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan, 35 per cent of workers under 35 years old have not saved anything for retirement. Meanwhile, 29 per cent of Canadians under 35 say they will likely have more debt in six months, and 83 per cent will be forced to postpone their retirement date if inflation grows.

The average income for those aged 25 to 35 is about $44,000 a year, according to Dundas Life.

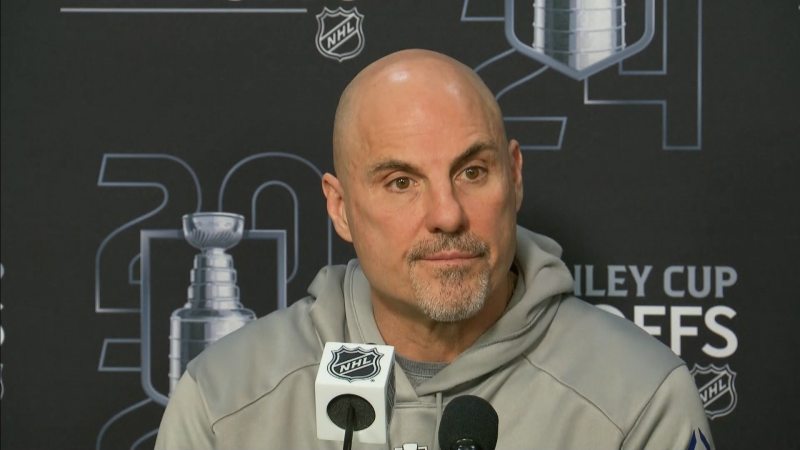

Sam Lichtman is a certified financial planner who educates millennial and Gen Z Canadians about financial literacy through his TikTok videos and podcast called Millennial Money Canada.

Lichtman says there are several tools available for young people to save their money more efficiently, such as utilizing a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP).

According to TD, an RRSP is a plan registered with the Canadian Government that allows you to contribute to it for retirement purposes. With an RRSP, you can set aside money that will be exempt from being taxed in the year you make the contribution.

“RRSPs can be a big help for your long-term retirement planning,” Lichtman says. “And it allows you to invest more money than if you invested in tax-free savings accounts because your contributions are pre-tax, and you’ll get a tax refund generated.

“If I can get taxed at an average tax rate of 25 per cent, but save tax when I contribute at 43 per cent — that's a huge difference.”

Another tool Lichtman recommends is the First Home Savings Account (FHSA). An FHSA allows you to contribute money, tax-free, with the intention of saving to buy your first home. Similar to an RRSP, the contributions you make to an FHSA will be tax deductible.

“The first home savings account is amazing,” Lichtman says. “For some people, even if homeownership is still a stretch for them, especially people living in places like Vancouver and Toronto, they can open an FHSA account and put up to $8,000 a year that is tax deducted.”

If you don’t end up buying a home within 15 years of opening the FHSA plan, you can transfer the funds within it directly to your RRSP.

Some millennials have the ability to contribute to an employer-sponsored pension plan, where employers will match a certain percentage of contributions to an employee’s pension or RRSP. Lichtman recommends his clients put as much as they can into employer-sponsored pension plans, “it’s basically free money.”

And for those who need help budgeting, Lichtman says the budget tracking and planning app Mint is a helpful way for millennials to keep tabs on their daily, monthly and yearly spending.

“It allows you to categorize your spending, and then it connects it right to your bank accounts and credit cards,” Lichtman says.

Mint users can connect their accounts to the app and set spending targets for each month. The app then sends users a reminder when they’re close to hitting their limits.

“It's a little bit of upfront work because you have to set those targets and goals, but I think it's really worth it.”