Following the “disappointing” announcement that two late-stage trials for a promising treatment for Alzheimer’s disease had been cancelled, a Toronto behavioural neurologist studying the drug says there’s still reason for hope.

Last week, pharmaceutical giant Biogen and its Japanese partner Eisai’s announced they would halt two phase three clinical trials – the clinical stage before going to market – into the drug aducanumab.

The companies said in a press release the decision followed an independent futility analysis conducted by a data monitoring committee, which found the trials were unlikely to be successful by the end date of January 2020.

“This disappointing news confirms the complexity of treating Alzheimer’s disease and the need to further advance knowledge in neuroscience,” Michel Vounatsos, Chief Executive Officer at Biogen, said in the press release on Thursday.

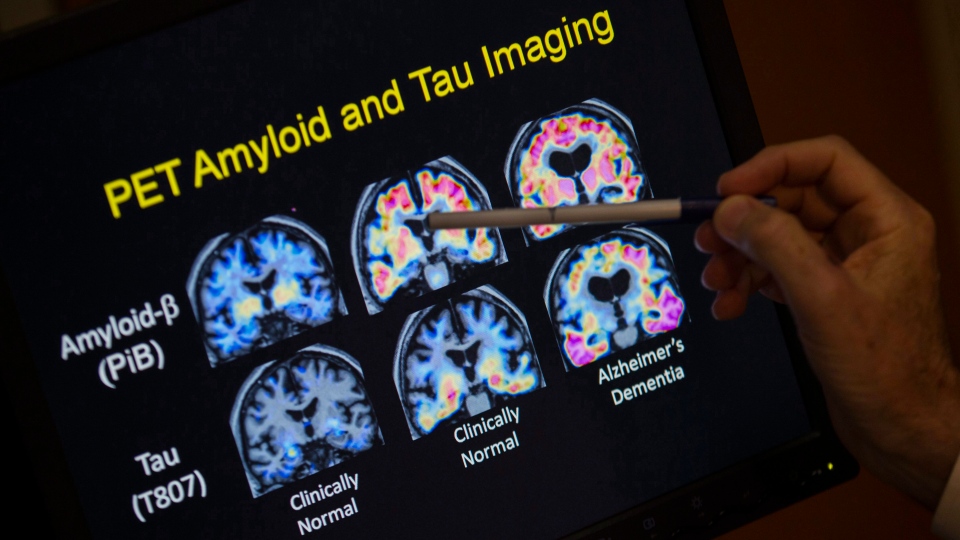

Dr. Sharon Cohen, a behavioural neurologist and medical director of the Toronto Memory Program who is the lead investigator in Canada for the drug, described aducanumab as an antibody that is shown to remove beta-amyloid plaque from the brains of individuals with early Alzheimer’s disease.

Beta-amyloid is one of two toxic proteins that researchers believe contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease, she explained.

Cohen said the first phases of the clinical trials showed aducanumab reduced amyloid plaque in the studies’ participants. The two phase three trials, which were recently cancelled, were intended to determine the effect reduced amyloid plaque in the brain has on people with Alzheimer’s disease.

“[It] was to provide further evidence, not that we’re reducing amyloid plaque, we know we can do that with aducanumab, but that actually people are better off. Their disease is halted or slowed down,” Cohen told CTV News Channel on Wednesday.

Biogen stressed that the clinical trials were not cancelled out of concern for the safety of the treatment, but because the independent data monitoring committee determined a successful outcome was unlikely.

“It was very disappointing that the futility analysis didn’t say ‘keep going,’ which would give us a lot of hope that we’re going to be successful,” she said.

Cohen said there are several hypotheses as to why the clinical trials didn’t produce the results they wanted. She said it’s possible the subjects in the trials had more advanced Alzheimer’s disease than they thought and there was already too much damage from amyloid plaque when they were given aducanumab.

“We know Alzheimer’s disease creeps up over 30 years and amyloid is building up for about 20 years before the substantial symptoms,” she said.

Cohen also said there is evidence to suggest amyloid isn’t the driving factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Instead, she said amyloid could be a trigger that sets off other toxic proteins, such as tau in particular, in the brain.

The behavioural neurologist said perhaps amyloid plaque needs to be treated at an earlier stage while tau is tackled at a more advanced stage in the disease’s progression.

Lastly, Cohen said amyloid plaque isn’t the same in every patient and it’s possible the treatment needs to be catered to different people.

Despite the setback for Biogen, Cohen said there’s still reason to be hopeful about the development of Alzheimer’s disease treatments. She said the large amount of data collected from Biogen’s clinical trials will be used to inform future studies, which are already underway.

Cohen also said there are already four studies in the world looking into the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. She also said there are lots of anti-tau compounds in development and in clinical trials.

“People are eager to see what tau can do. Probably in the end, we’ll need a combination and stage therapy of amyloid therapies early on and tau for later stages,” she predicted.

“The scientific community is not giving up.”