The news that four cases of measles have been confirmed in Toronto has worried some parents and set off a debate online about a disease that should be wiped out in Canada -- but still keeps popping up.

CTVNews.ca separates the fact from the fiction.

Q. What is unusual about these measles cases in Toronto?

On the one hand, it's easy to see why the four patients got infected: three were not vaccinated, and one had received only one of the two recommended doses. But public health officials are also worried there may be more cases in the city that haven't yet been reported.

That's because none of the patients had recently travelled to an area where measles is common, meaning they didn't pick up their infections that way. And none of them had contact with each other. That means there's a good chance there are other people in the city with measles who passed it onto these four -- and could still infect others.

Q. Remind me again how I can catch measles?

The measles virus is spread mostly through the air, through coughing and sneezing. It can also be passed on by sharing a cup or utensil with someone who is infected.

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases around. The virus has a way of easily attaching to your mucous membranes, such as your nose or mouth, and from there, it spreads throughout the body.

Q. I'm healthy and rarely get sick. How likely am I to get infected?

Measles doesn't care how healthy you are. If you're unvaccinated and come into contact with it, there is a very strong likelihood you'll become infected. You could walk into a room where a person with measles had coughed two hours ago and catch the virus from tiny droplets still hanging in the air. It's that infectious.

What's more, measles is one of those illnesses that's contagious even before the big symptoms kick in. It can be transmitted up to four days before an infected person even develops the telltale rash.

Q: I've read that measles isn't all that bad and that most people get better quickly.

It's true that the majority of those who become infected will recover in two to three weeks. But it's an illness that will leave you feeling wiped out, like the flu, with fever and fatigue. And let's not forget that uncomfortable rash.

As well, a large number of patients -- around 20 per cent -- will develop some kind of complication. That could be something not too horrible, like mouth ulcers or an ear infection. Or it could be something more dangerous, such as pneumonia, which accounts for most measles-related deaths, particularly in babies and little children.

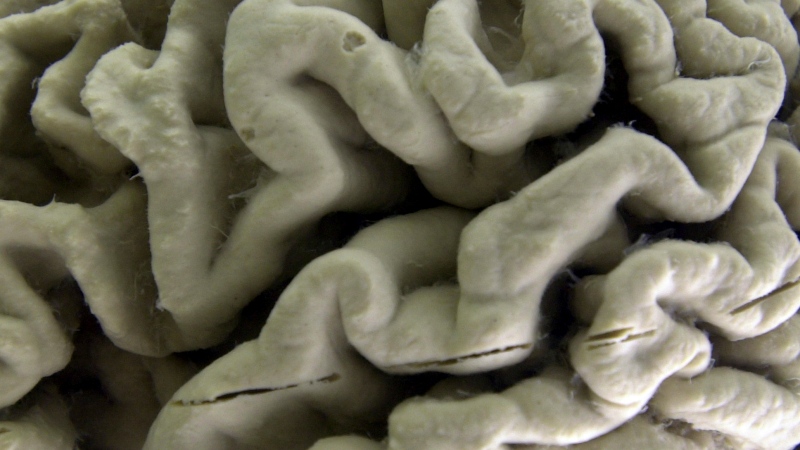

The disease can also lead to blindness, ovary inflammation (oophoritis), encephalitis (swelling of the brain), hearing loss, or even developmental delays.

And let's remember that there is no treatment for measles. All that doctors can do is manage the symptoms and wait for it to run its course.

There's one more drawback to catching measles. Even if you get a mild case, you will still need to quarantine yourself for three solid weeks -- 21 days. That's a lot of loneliness.

Q: Why do people still catch measles if most of us are vaccinated?

For one thing, no vaccine is 100 per cent effective. The measles shot -- contained in a vaccine called MMR or MMRV -- is one of the most effective vaccines we have. But for some reason, it doesn't work on everybody. A small percentage of those who get both recommended doses (about two per cent) will not mount enough of an antibody response and can still get infected. Doctors don't know why that is, but they do know that vaccinated measles patients end up with a milder form of the illness.

Secondly, there are many people who can't be vaccinated, particularly infants under the age of 12 months, or people who have shown they are allergic to any component of the vaccine. Some people with immune diseases or those undergoing cancer treatment may not be able to receive it, though some can.

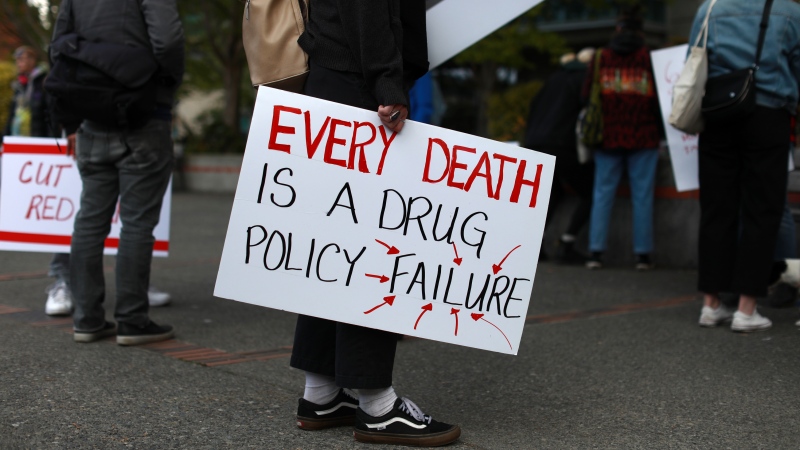

Then there are the unvaccinated. As we have all heard, there are many people who choose to disregard the advice of public health experts and not vaccinate themselves or their children -- the so-called "anti-vaxxers."

But there are also people who are unaware they are not fully vaccinated (meaning two doses). Others are unable to access health care because of poverty, lack of access, or language barriers.

That's why it's so important that those who can get vaccinated get the shot -- to create "herd immunity" and protect those who can't.

Q. I know everyone says vaccines don't cause autism, but what about the other stuff in them?

The 1998 study that suggested that the MMR vaccine can cause autism was fully retracted a few years later and the doctor who performed the study lost his medical licence. As well, no peer-reviewed studies were ever able to replicate his findings. Public health experts consider the debate over.

As for concerns about additives such as thimerosal, there is no good science showing that the preservative is dangerous when it's used in a vaccine. Also, no vaccine given to kids in Canada contains thimerosal, except the flu shot. In fact, the MMR vaccine in Canada has never contained thimerosal.

Some also worry about the aluminum salts in vaccines, but the metal is safe in tiny amounts. A dose of over-the-counter antacids has as much aluminum salts as a vaccine, but few worry about them.

Q. But it's false to say there are no risks to the vaccine, right?

The vaccine carries the risk of side effects, but they are very mild. Bruising and soreness at the injection site is considered a "side effect," but it's hardly dangerous. One in six people will develop a fever, but that, too, is not dangerous. Mild rashes occur in one in 20 cases, but those usually go away quickly.

Serious allergic reactions happen in a fraction of cases. Other more serious side effects -- such as seizures or brain swelling -- happen so rarely, doctors often can't be sure the vaccination had anything to do with them.

Compare that one-in-a-million chance to the one-in-10 chance of developing pneumonia from measles, and the risks really can't compare.

Q. How do I know if I've been vaccinated?

Anyone born before 1970 is considered immune to measles, as the virus was circulating widely at that time and they were likely infected, developing natural immunity.

For many years, it was thought that one dose was enough. But in 1996 and 1997, every Canadian province and territory added a second dose of measles-containing vaccine to its routine immunization schedule, and most conducted catch-up programs in school-aged children.

If you don't know whether you were fully vaccinated as a child or whether you got the catch-up shot, start with your parents or the family doctor you had as a child, who might still have a record.

Public health units also keep records. If that doesn't work, it's best to talk to your current health provider and see whether you should have blood tests to determine your immunity. In many cases, it may be best to simply get a second dose than risk being under-vaccinated.

Remember it is the responsibility of parents to ensure they keep their child's immunization records up to date with their public health units. Kids who are unvaccinated may be at risk of being suspended from school.