For the thousands of Canadians who suffer serious knee injuries each year, their only option is often surgery to replace the damaged joint with a plastic or metal implant.

But a team of doctors in Hamilton, Ont. are the first in Canada to try out a novel approach: growing sheets of cartilage in a lab using a patient’s cells and then cutting custom-fit implants from the patient’s own DNA.

The method is currently being tested across North America on 230 patients with knee injuries. Doctors say that if the study is successful, lab-grown cartilage could become a common way to treat a host of joint problems, from ankles to elbows to shoulders.

Salim Lakhi, a 20-year-old student from Kitchener, Ont., was rock-climbing in South Africa with his mother when he fell from a height of about three metres. He immediately felt a sharp pain in his right knee and was unable to walk for a few days, but assumed the pain would eventually go away.

“I just bandaged it up and I thought it was fine,” Lakhi told CTV News.

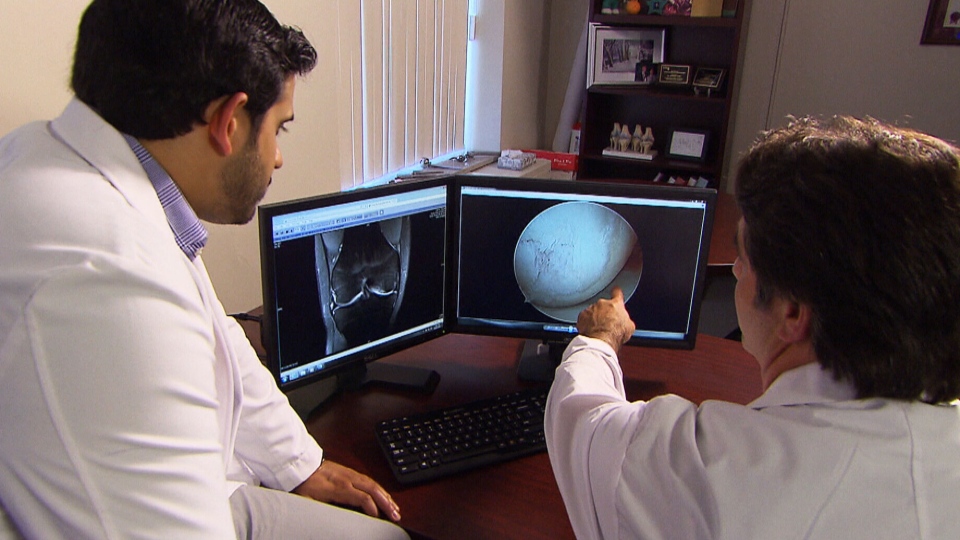

But the pain only got worse. Lakhi eventually went to a doctor, where he learned that he had seriously damaged his knee. Dr. Anthony Adili, an orthopedic surgeon at St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, likened the injury to a tiny “pothole” in the cartilage.

“These aren’t great injuries to have as a young individual because we know that 10, 15 years down the road with these types of lesions, it likely will develop into a very arthritic compartment, if not arthritic knee,” Dr. Adili said.

Typically, treatment involves drilling into the damaged area of the knee, thereby allowing scar tissue to form. If everything goes according to plan, the scar tissue helps relieve discomfort until the patient is able to receive a knee replacement.

But a different solution was open to Lakhi -- one that didn’t require a knee replacement. St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton is involved in a randomized, clinical trial that would allow doctors to carefully fill the tiny cartilage “pothole.”

In August, surgeons in Hamilton collected a tiny sample of healthy cartilage from Lakhi’s knee and sent it in a test tube to a clinic in Pittsburgh. There, a team of scientists harvested the cartilage into a larger sheet and sent it back to Canada.

Doctors in Canada then cut a tiny piece of cartilage from the sheet to plug the hole in Lakhi’s knee. The surgery went “very, very well,” Dr. Adili said.

“We were ecstatic, especially being the first in Canada to do it,” he added.

“The hope is that when it grows, and it heals back into that defect, it’s going to be his normal cartilage, and he’s back to where he was before this injury.”

The trial is still in its early stages. Lakhi and 230 other patients will be tracked for the next two years to determine if the transplants worked.

Lakhi is still using crutches and can’t put any weight on his leg for another three weeks, but the pain has subsided and he hopes to see progress soon.

“I am pretty optimistic about it,” he said. “I am feeling really good. My knee is feeling alright when I bend it and I am hoping I can get back to sports after.”

In Canada, more than 67,000 patients undergo surgery for new knees each year. If the experimental method proves effective in the knee, it could have a widespread use, Dr. Adili said.

“If it’s proven that this works in the knee, then you can really foresee that you could actually do this in the hip joint, you can do it in the ankle joint, you can do it in the shoulder joint, you can do it in the elbow joint,” Dr. Adili said.

With a report from CTV Medical Correspondent Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip