TORONTO -- Modern medicine means that today’s doctors are usually heavily armed with knowledge, experience, equipment and procedures to effectively fight illness and disease in their patients.

Not so with COVID-19.

The novel coronavirus has been on the radar for only a few months and though doctors and scientists are racing to gather information, little is really known about how it attacks the body and how best to treat it.

That weighs heavily on Dr. Ariel Lefkowitz, an attending physician at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre who was put in charge of all the COVID-19 patients who were not in the intensive care unit when the pandemic hit in March.

He’s 32 and just two years out of his medical residency.

He says while patients fight to breathe and to battle the virus, he can offer little more than oxygen and compassion.

“I think that we forgot what it was like to practise medicine in the 19th century,” he told CTV News.

“But here we are with a disease where, you know, outside of clinical trials all we can provide is oxygen and support and monitoring. And so, as a physician caring for patients with COVID, I found that, you know, one of the most important things I could do was show compassion because we didn't have any other treatments that we knew were effective.”

What has surprised him most about COVID-19 is its trickiness. The symptoms can be hard to read, carriers can have it and not know it, the road to recovery is often long and rocky.

“It was stressful because this isn't just a disease that gets worse and then gets better. It can get worse and better and then worse again. So I found that very, very surprising and tricky and disheartening.”

One of Lefkowitz’s patients was Manor Haas, a fit, 48-year-old father and dental surgeon. He caught the coronavirus while on a Caribbean trip.

“It was the worst flu I could imagine times one hundred and just kept getting worse and worse,” he said. He had fever, achy joints, night sweats and weakness. At first, he tried to pass it off to being tired from his travels, but he knew his symptoms fit with the virus.

But then he passed out and found himself admitted to Sunnybrook, where it wasn’t long before he was fighting for his life.

“That is when it became frightening,” he said. “I did not want to get ventilated because I sort of knew what that might mean.”

Lefkowitz, a married father to a two-year-old boy, knew his patient was scared and he was scared for him. He told him they would get through it together. He’s mindful with all his patients, battling this virus without loved ones at their side, that showing human caring is one of the most important aspects of his job in this pandemic.

The doctor came to work each day hoping to see Haas getting better.

“We almost made it to Day 14 when you're out of the woods, but unfortunately, he got worse and needed to go on a respirator.”

Lefkowitz, who documented his stressful and agonizing experience on the COVID-19 ward in a powerful Toronto Life memoir, says that broke his heart.

Ventilators can sustain lives, but they can also damage vocal cords and that’s what 76-year-old Beny Maissner feared when he was hospitalized with COVID-19 after returning from a trip to Israel.

About eight or nine days after returning to Canada in mid-March, Maissner started to feel unwell. He was running a fever and his doctor told him to go to the hospital.

“The first day they told me if it really gets bad, they’ll have to intubate me.”

But Maissner, a cantor in a Toronto synagogue, was worried about his voice. If a ventilator was necessary, he asked doctors to do everything they could to protect his vocal cords.

The worry turned out to be for nothing. Maissner recovered without ventilation.

“I feel very, very lucky to be alive,” he told CTV News. “It's important that the world knows that there are cases of recovery.”

He hopes others can take encouragement from his story.

As does Haas, who after two weeks on a breathing machine, started to breathe on his own.

“I was so happy, so relieved. I will get to see my kids again and my wife and family and friends.”

He’s now back out riding his bike and sharing his experience with colleagues.

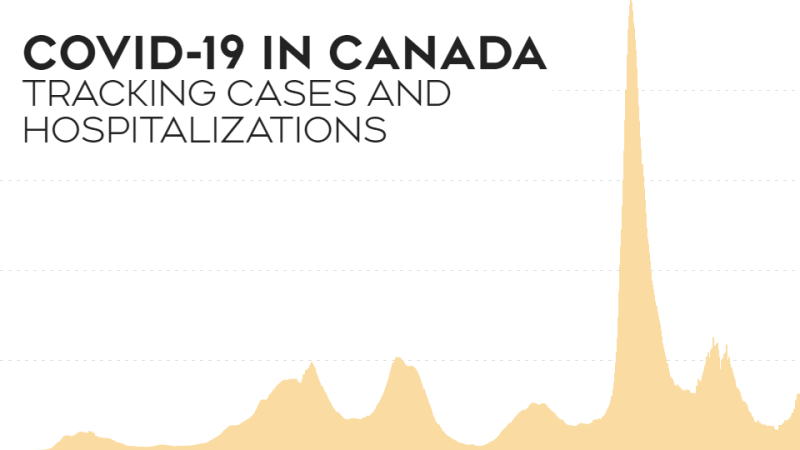

In Canada, the virus has claimed more than 7,700 people and sickened more than 94,500 so far. Almost 396,000 have died and 6.8 million have contracted the virus worldwide

For Lefkowitz, the stories of survivors like Haas and Maissner give him hope.

“I am over the moon thrilled, I can't even tell you, I saw many people not make it,” he said at his home.

“The ability to go all the way up to the doorstep of death in the ICU and to be able to turn around and come back, makes me heartened that there's another side of this for all of us in society.”