TORONTO -- Grassroots activism was a driving force when informing the public about the HIV/AIDS epidemic information, and that same sort of messaging may be the key in sharing clear and concise messaging about the COVID-19 pandemic.

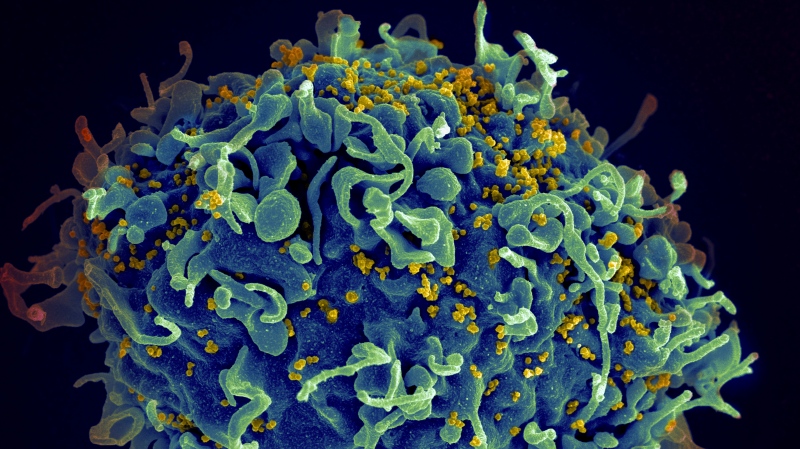

In the early 1980s, AIDS was spreading globally. Initially thought to only impact gay men, in the years after it was first discovered, scientists and doctors learned it could be transmitted sexually or via blood-to-blood contact, as well as in utero or through breast feeding. According to UNAIDS, 32.7 million people have died as a result of AIDs since the epidemic began in 1981.

Because it was caused by a novel virus and due to the associated stigma for those who were infected, AIDS activists of the late 1980s and early 1990s had little choice but to become experts in their own healthcare.

A key ingredient in the work of early AIDS activists was coming together as a collective, according to associate professor of sociology and anthropology at Carleton University Alexis Shotwell.

“The main thing we can learn now is to really be working with other people and learning from each other and figuring out what power we have together,” Shotwell told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview.

The first AIDS activists were predominately gay men as it was initially believed they were the only ones who could contract the virus. Originally named Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GIRD) in 1981, it wasn’t until 1983 that it was discovered that women could get AIDS through heterosexual sex.

For Shotwell, there’s a lot to learn from the early AIDS activists who fought back against the condition being a death sentence, and put in the work to find treatments.

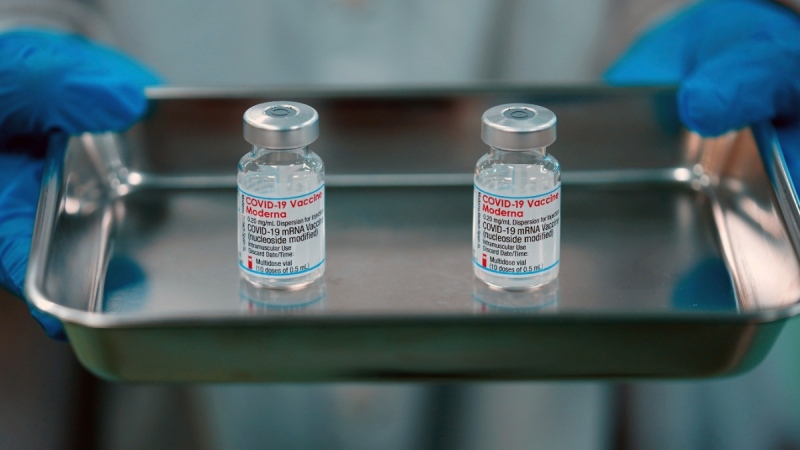

“We could learn from AIDS activists to say what treatments should we be looking for? Treatment activism is a big thing we could learn,” she said.

There’s still much to learn from COVID-19 long-haulers, and long-term effects of having contracted the virus that we need to focus on the future, Shotwell said.

“One thing I’ve learned from studying the history is the necessity or importance of people having some sense of the long-term. This is going to affect our lives forever.”

For Christian Hui, a Toronto-based AIDS activist, there’s a lot to be learned from people who contract the virus, in both the HIV/AIDS epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic.

“People and communities are resilient, and it is essential that policy makers engage people who live/have lived with the viruses (people living with HIV; people with long-haul COVID-19) to inform the creation, implementation, and evaluation of policies and pandemic response plans,” he told CTVNews.ca in an email.

This idea of collectivity rings true for Hui, who suggests the coronavirus pandemic underscores the importance of coming together.

“I think the mass impact of COVID-19 has made many realize that us as citizens do not function well living in isolation, and addressing global crises such as HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 truly require all in society, in our various roles, to work together.”

“I think the main thing that they had that we need to build is collectivity, it’s really important that we can know things and share,” said Shotwell.

Unlike decades ago at the height of the AIDS crisis, in an era that predated social media, sharing information is now easier using the likes of Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

CANADA’S GRASSROOTS MOVEMENT

AIDS activists worked to disseminate public health messaging and translate it into terms that would resonate with people, and catered it to their lifestyles. This targeted messaging was missing in Canada’s COVID-19 pandemic, and one woman took up the opportunity to tailor messages for millennial and gen-Z Instagram users.

ON Canada Project, an Instagram account targeted at millennial and gen-Z groups, aimed to engage with younger generations and address the unique issues they face throughout the pandemic. Through the power of social media and shareable content, they’ve translated public health messages into easily digestible infographics.

Canada’s public health guidelines and restrictions on COVID-19 haven’t provided younger generations with necessary information, like how to live with roommates during a pandemic, how can an 18-year-old see their family if they’ve been away at school, or is it safe to continue dating someone who isn’t in your household? They’ve also become a target throughout the pandemic, blamed for not taking it seriously and causing further spread.

For Hui, this kind of grassroots messaging is very effective.

“Grassroots activism and movements often lead to the best advice and often force the government to act where it has failed to do so,” he said.

What started in May 2020 as a three-women grassroots social media movement born out of frustration with the official messaging now has 11,100 followers and over 100 volunteers making COVID-19 information accessible.

“I looked everywhere, and I didn't see this sort of messaging that would resonate with me and my friends,” Samanta Krishnapillai, ON Canada Project founder and executive director, told CTVNews.ca in an interview on Tuesday.

Krishnapillai said that what was missing was messaging that was clear and focused on compassion and empathy that resonates with younger generations.

Spoofing lyrics from TLC’s hit ‘Waterfalls’ to convince people to stay in their bubbles was a hit.

For Krishnapillai, placing the burden of deciphering medical terms and guidelines on Canadians and requiring a medical background just to navigate daily life in a pandemic was unjust.

“Having to have a prerequisite for a school program or course to navigate a global pandemic that impacts all of us to varying degrees, but impacts all of us, seemed unfair, fundamentally unfair,” she said.

She has a degree in health sciences, and felt that a lot of the messaging was above the average Canadian’s medical expertise and understanding.

Canadians were expected to adapt to the onslaught of scientific and medical information and determine how it impacted their daily lives when they should’ve been given a more tailored, simplified message.

“The expectation was on people to adapt the messaging to themselves, versus a message that was adapted to different community groups, different ways of life, different levels of what you’re able to adhere to with the guidelines,” she added.

The expectation, she said, was for everyone to figure it out for themselves, so she took it on herself to create ON Canada Project to help her fellow millennial and gen-Z Canadians better understand what they were being told, and how to handle situations specific to younger age groups.

“I think that Millennials and Gen Z have been left out of every conversation,” she said.

Part of what Krishnapillai did to appeal to younger people was to craft very clear messaging in an easily shareable form.

“I knew that if I wanted it to be shareable, which allows us to get in front of people not following us, which is who we want to see the messaging, then it had to be cute.” she said.

Their infographics are often provided in a variety of millennial and gen-Z friendly colours, for example.

A big factor in getting the right messages out has been engaging with the community, reading comments and direct messages and even asking their audience questions.

“One of the things I think we do really well that I wish more public health and official people would do is we use the two-way communication tool of social media. It's not a billboard. It's not old school messaging. It's a two-way street,” she said.

She’s not the only one to notice that audience engagement is key to getting the right message out.

“It's an audience-first strategy. Everything we do is engagement, engagement. We read every single comment, we read every single reply, we follow the local influencers, we follow all the local media outlets,” Kevin Parent, Ottawa Public Health social media lead, said in a phone interview on Tuesday.

Ottawa Public Health tailors its messaging using audience engagement on their social media and local media stories to determine how people are reacting. And they’ve been praised throughout the pandemic for it, with Maclean’s dubbing them “North America’s top public health Twitter account.”

“It's about maintaining that public trust, trusting public health is the key to this entire thing,” he said.

And gaining and maintaining that trust during a pandemic when things are changing so quickly means acknowledging the frustrating nature of the changes and explaining why changes are being made, he said. That’s exactly what they tried to do with a Twitter thread breaking down why the information about COVID-19 has been changing.

HOW TO GET THE MESSAGE ACROSS

The best way to spread the message is to do so simply, Parent and Krishnapillai both say.

For Krishnapillai, she’s trying to tailor messages to those whose scientific knowledge might be informed by Bill Nye, the “science guy.”

“So how would you communicate to that person you love and that person that you want to make safe choices?” Krishnapillai said.

For Parent, it is about boiling down complex ideas and putting them in plain language.

“That's been our strategy for a couple of years of just trying to be human, be real, be genuine, not do typical, you know, corporate bureaucratic comms.”

Ottawa Public Health has a knack for putting things into terms and scenarios that Ottawa citizens will take seriously.

Edited by Kieron Lang