Canadian researchers have begun a trial using genetically enhanced stem cells in the hope they can repair a patient's heart muscle after a major heart attack.

The researchers, who announced the start of the study Thursday in Ottawa, believe they are the first in the world to test genetically boosted stem cells as a possible means of rejuvenating severely damaged heart muscle.

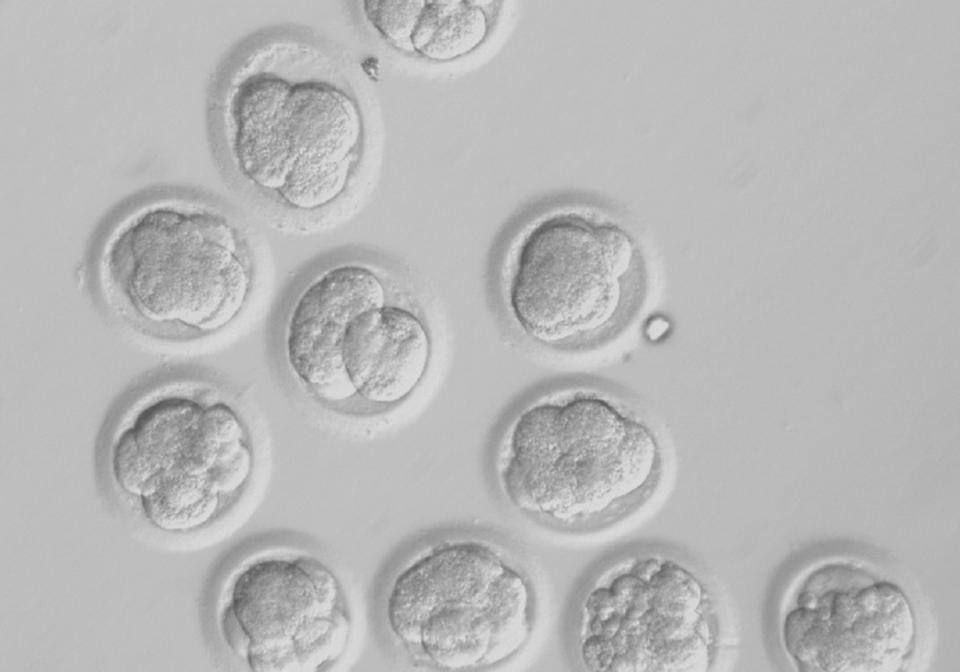

The experimental therapy uses stem cells extracted from a patient's blood within days to a few weeks after a major heart attack, said principal investigator Dr. Duncan Stewart, CEO and scientific director of the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

Scientists enhance these progenitor cells with a gene called endothelial nitric oxide synthase, which is known to stimulate blood vessel growth and improve tissue healing. These beefed-up stem cells are then infused into the patient's heart through the coronary artery involved in the heart attack.

"Stem cells have incredible potential to repair and regenerate damaged organs, but cells that come from heart attack patients don't have the same healing abilities as those from young, healthy adults," said Stewart. The cells are as old as the patient and have been exposed to the same factors that led to the heart attack.

"Our strategy is to rejuvenate these stem cells by providing extra copies of a gene that is essential for their regenerative activity, so that they better stimulate heart repair, reduce scar tissue and restore the heart's ability to pump blood efficiently -- in other words to help the heart fix itself."

Harriet Garrow, who suffered a major heart attack in July, is the first patient to have been treated as part of the two-year trial, which will enrol 100 patients at a number of centres in Canada, starting the University of Ottawa Heart Institute and St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto. Other hospitals in Montreal and Toronto will be added.

Garrow, 68, isn't sure which therapy she received. The study is a double-blind, randomized control trial, meaning that patients are randomly selected to get one of three treatments -- the genetically enhanced stem cells, non-enhanced stem cells or a placebo preparation.

Blinding means neither the patient nor the researcher administering the therapy knows which one is being used.

Garrow, who had her heart attack while at her Cornwall, Ont., home, said she of course hopes she received the enhanced stem cells.

"I feel really good. I get better every day, stronger," Garrow said in an interview from Ottawa, though she admitted to getting fatigued if she overdoes it physically.

Stewart said the study is meant to determine if the stem cells -- and, in particular, the genetically altered stem cells -- are superior to placebo, or in other words providing no treatment.

"Their hearts have been severely damaged, and they have a significant risk," he said. "As the heart scars it becomes weaker. And this is a vicious circle where the heart enlarges and becomes weaker and weaker, so it's a risk of heart failure, sudden death, readmissions (to hospital), chronic disease and premature death.

"So what we're hoping is that this kind of therapy can improve the healing of the heart, produce less scar, more functional heart muscle and be able to prevent that cycle."

Stewart said the study has been more than a decade in the making and is a collaborative effort, which has included Dr. Michael Kutryk, the principal investigator at St. Michael's Hospital.

"Researchers at St. Michael's Hospital have played a key role in the early development and testing of this new therapy from the very beginning, and we're delighted that this groundbreaking clinical trial is now underway."

"It's been a labour of love to get this going," agreed Stewart, adding that results from the $4-million trial likely won't be ready for another three years.

"It's a very ambitious trial and there is a lot of international interest in this."