Researchers at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto are working on what they call a new class of "sharpshooter" drugs they hope will slow the growth of a number of forms of cancer tumours, including breast and prostate cancers, as well as colorectal and brain cancers.

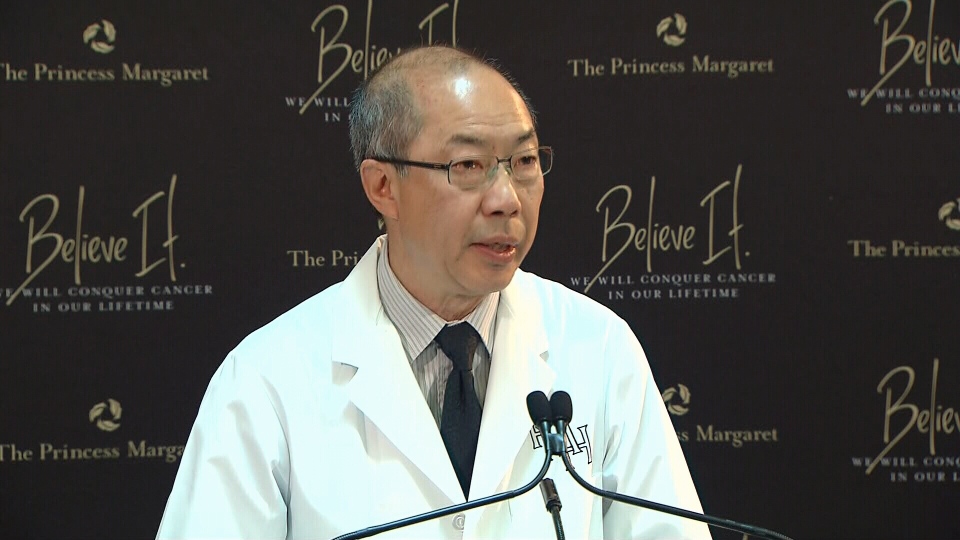

Dr. Tak Mak, directors of the centre, and Dr. Dennis Slamon of UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) say their team is developing a new drug that targets an enzyme called PLK4, which plays a key role in cell division, particularly in cancer cells.

The drug they developed over the last 10 years, known as CFI-400945, appears able to inhibit the growth of human breast and ovarian tumours in experiments on lab mice. It also appears effective on colorectal, glioblastoma, lung, melanoma, pancreatic and prostate cancers.

The research team now wants to test the drug in patients, and hopes to gain approval from the FDA and Health Canada to enter clinical trials in the months ahead.

The drugs are called “sharpshooters” because unlike traditional chemotherapy drugs which attack all fast-dividing cells -- cancerous or not – this class of drug is designed to target cancer cells only, leaving healthy cells alone.

The drugs seeks out “genomically unstable" cells with the PLK4 enzyme that have many more chromosomes than the 46 that normal cells have.

The researchers hope to have regulatory approval by the fall to begin human trials, beginning their study trial by the end of the year.

The first phase of testing would assess the safety of the drug in around 30 volunteers with breast or ovarian cancer. That testing should help determine how strong a dose can be tolerated.

The next phase of testing would assess its effectiveness.

If all goes well, Mak estimates it could be less than 10 years before the drug is approved for widespread use.

Dr. Mak cautioned that, so far, they have only tested the compound in mice and there are still questions that need to be answered about how it will work in humans.

“I cannot promise you that it will work because in advanced human cancer there are many other questions that we have not the answers to,” he told reporters at a news briefing Tuesday.

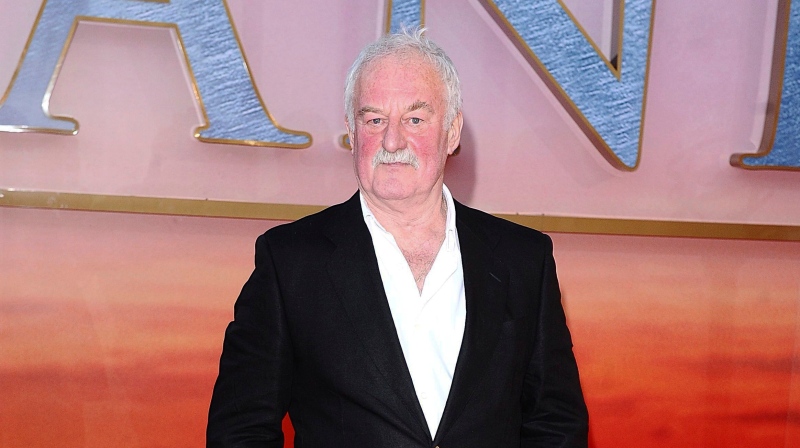

Dr. Slamon, best known for his development of the cancer drug Herceptin, said he remained hopeful.

"I truly believe in this important discovery and its therapeutic potential for cancer patients," he said in a statement.

The team promised it also has other compounds in early development that aim to target other newly discovered proteins.

“We promise you this is the beginning,” a clearly excited Dr. Mak told reporters. “There will be another drug that we will be filing for next year, and next year and next year, until we get this done.”

The researchers say they were able to make their discoveries and advance them to the point where they are ready to test a drug in patients almost solely through support from Princess Margaret Foundation donors.

“It is extremely rare for an academic group to have discovered and advanced a novel, ‘first-in-class’ drug candidate to this level, and it would not have been possible without the fundamental support provided by donors,” the researchers said in a news release.