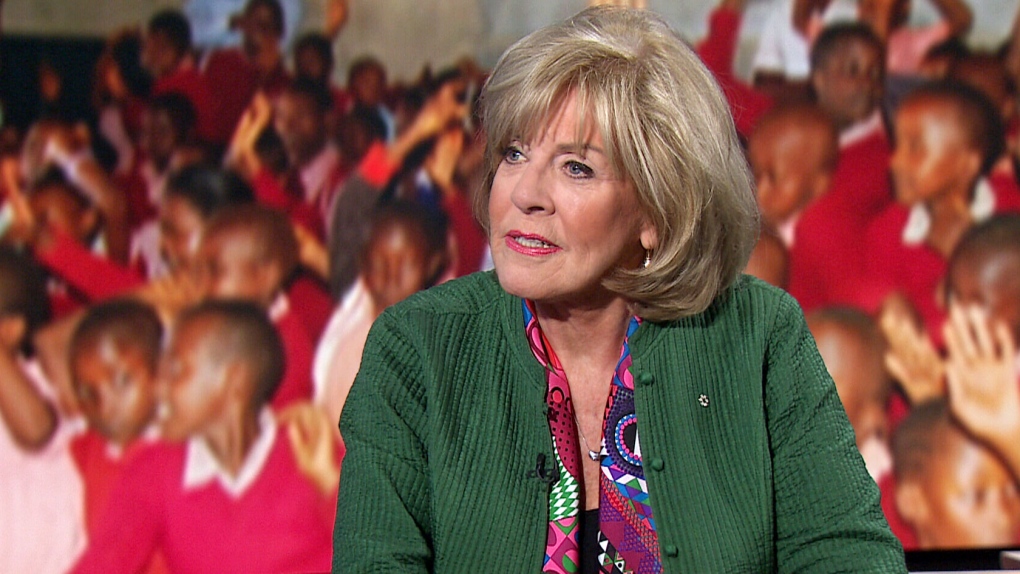

Canadian journalist Sally Armstrong is documenting efforts to combat a widespread culture of rape in Kenya, where one third of girls fall victim before the age of 18.

“Justice Clubs” teach children about their right to be protected from rape. Canadian law enforcement officers have assisted the project, training Kenyan police on how to investigate sexual assaults, gather evidence and pursue convictions.

It started when 160 girls sued the Kenyan government for failing to protect them -- and won.

Armstrong, who travelled to Meru, Kenya to witness the end of the Canadian training mission and the launch of the Justice Clubs, spoke to CTV Chief Anchor Lisa LaFlamme about the fight for justice. Here’s a full transcript of their conversation.

LaFlamme: I look at those pictures and I see those numbers. It’s almost hard to compute that one in three girls is raped.

Armstrong: It is. You know, they say that many men think that having sex with a small girl will cure them of HIV-AIDS. It’s practically an epidemic.

LaFlamme: So it is part of the culture then. How difficult was it to have it even recognized as a crime?

Armstrong: Well, one woman recognized it and she said, to use her words, she was "fed up with washing the floor," bringing these kids in to shelters, trying to protect them, because they knew who’d raped them. It was their uncle, their brother, their teacher, their priest -- the very people struck with the responsibility of looking after these kids.

LaFlamme: Or, in some cases, police officers. We know that the statistics are also very high for police taking advantage of girls and women in the community. So how did Canadian law enforcement get involved in this?

Armstrong: This woman, who was running the shelter, her name’s Mercy Chedi – she’s like the Erin Brockovich of Africa, really. She came over to Canada to take a course at the University of Toronto and she ran into Fiona Sampson. And that’s the woman who runs an organization called the Equality Effect, that uses international human rights law to alter the status of girls and women. She told her the story. Now, Fiona Sampson is also Canada’s last-born thalidomide child – she knows a thing or two about impunity. The two of them got together and said, 'This has to stop. We’re going to sue the government of Kenya.'

LaFlamme: The concept of suing the government for not protecting girls is overwhelming. Now, I know this was a multi-year battle to get that victory. But that was 2013 that they won. What kind of progress have they seen in bringing numbers down?

Armstrong: This is the best part, really. They had this huge win, which was for 10 million girls they won it for. But what are you going to do with the win? If you don’t change the status of girls on the ground, the win is worth nothing to you. They had to retrain the police. Huge job. Very expensive and very lengthy. And you have to be pretty sensitive to do that. And this is where the story really picks up, because who stepped in to do this job? Two officers from the sexual assault squad of the Vancouver Police Department.

LaFlamme: How did they even get involved in this?

Armstrong: Fiona Sampson contacted Insp. Tom McCluskie and she said – this is when the case is going to court – I need you to look at these cases and tell me, would these cases ever have have found a conviction? He said, 'Absolutely not, they’re not done properly.' So, she’d already met him. He was working on the (Robert) Pickton file at the time and she went back to him when they won and said, 'I need you again, will you come back?' (So he goes to Kenya) with his partner, Sgt. Leah Terpsma.

LaFlamme: How did Canadian tactics on investigating rapes and seeking convictions translate to Kenya?

Armstrong: You know how smart they were? They brought the top 12 police officers of Kenya to Toronto for a five-day training period. Obviously, they were looking for buy-in and they got it. So then they went back together. It was one of those "train the trainers" (things). Leah Terpsma and Insp. McCluskie – it almost sounds like a movie – work for three years to do the training and in March they handed it over to the Kenyan police to complete it.

LaFlamme: What was that like for you?

Armstrong: It was incredible. I was so proud to see this happening, because at the same time, the 160 girls, they wanted some legacy. They wanted other girls in Kenya to know what they had gone through and why they went through it for all of them. But they’re kids and they didn’t know how. They kept talking about having people come together through dancing, singing, debating, working with the community. So who steps up to fix that problem? The University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management. They handed it to the MBA students, said work with them remotely and figure it out. And they did. So at the same time the police turned over the training, the launch of the Justice Clubs happened the same day. It was in 12 schools, they’re pilots, but they’ll have them in all the schools. And it’s to tell the kids, what is the responsibility of the state to you as a citizen, and what does the law mean to you as a girl? I think it’s brilliant. I was so proud of Canada.

LaFlamme: This is such a little known co-operative that we wouldn't learn about, that so many levels in Canada are participating in this. We see the girls wearing the T-shirts, 160, it’s become almost of catchphrase?

Armstrong: It has. You know, they’re incredibly empowered. They’re victims of course – what a terrible thing happened to these kids. But they know that they did that their grannies and their mothers and their older sisters and their aunties never pulled off. And they’re incredibly empowered by all of this. And it passes along. I went to two of the schools in the bush and they get it. The boys as well.

LaFlamme: Will it force change?

Armstrong: One of the police officers said to us at the end. He said to us, 'You know, I used to look at this in a different way. Now I look at it as a father.' And you know what the penalty is? If you rape a child who is under the age of 15 it’s life in prison.