The advances in HIV-AIDS treatment in the last decade have been nothing short of amazing, transforming the virus from what was once a death sentence to what is now a manageable disease.

Antiretroviral medications keep levels of the virus in carriers so low, they are often almost undetectable, greatly reducing the risk of ever passing the virus on to sexual partners.

Given those changes, does it make sense to charge those who don’t reveal their HIV status to their new sexual partners with sexual assault, the same charge we lay against rapists?

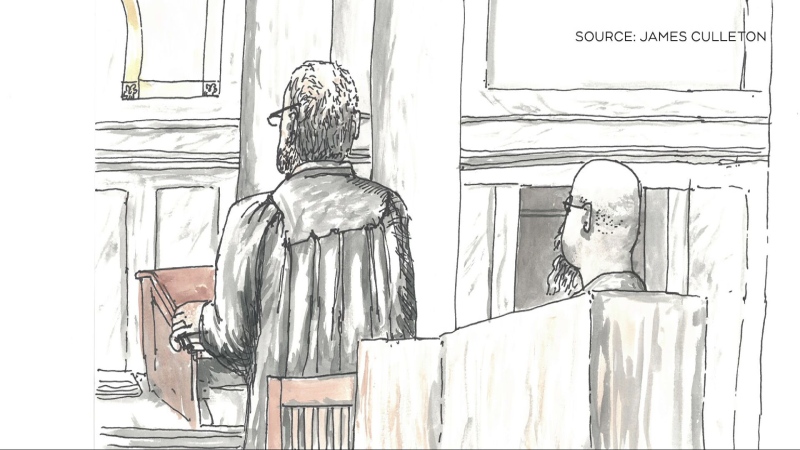

That’s the question currently before the Supreme Court of Canada. Lawyers on both sides of the debate argued their positions before the court in February. Now, with the court back in session after a summer break, a decision on the matter is likely to be handed down shortly.

There is currently no law in Canada that compels those with HIV to tell their partners about their illness. But in a landmark case in 1998, called R. v. Cuerrier, the Supreme Court ruled that when sexual activity poses a “significant risk of serious bodily harm,” there is a duty on the HIV+ partner to reveal their status.

If they don’t, their sexual partner can argue they did not have enough information to give their full consent to sex, and the HIV+ partner can be charged with sexual assault.

The HIV-AIDS community has argued that a lot has changed in the 14 years since the Cuerrier decision. And yet, criminal charges continue to be laid.

The Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network says more than 140 people living with HIV have faced charges since the Cuerrier ruling for failing to tell their partners about their status, says the group’s senior policy analyst, Alison Symington.

“And around 2004, we started to see an escalation in the number of charges,” she tells CTVNews.ca. “It’s odd to see that at this point in the epidemic when there’s so much good news about how we can treat this illness.”

The case before the Supreme Court can essentially be divided into two arguments: Those who all HIV carriers should be compelled by to disclose their status to any sexual partners; and those who say the only ones who should ever face charges are those who do little to protect their partners.

Those in the first group argue it doesn’t matter if HIV carriers are on medications that reduce the risk they’ll pass the virus on; there is still a risk, even with the drugs.

“You must tell prospective partners if what you bring to the table can cause significant harm,” Manitoba Crown attorney Elizabeth Thomson told the nine-justice panel in February.

“The threat of HIV is not theoretical. The threat is still real.”

While the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network agrees that criminal charges might be warranted in some circumstances, such as the intentional transmission of HIV, it says the law should never be used against those who take steps to avoid passing on HIV.

They say the majority of those living with HIV are under treatment and know they need to use protection during sexual encounters and the Supreme Court should make it clear that in most of those cases, the risk of transmission is not “significant.”

“Our group says we’d like to maintain the ‘significant risk’ test but update it and clarify it so that it corresponds with the reality of what it means today to live with HIV,” Symington explains.

Quebec Crown attorney Caroline Fontaine argued to the court that it’s not realistic for police and the courts to be asked to estimate how well the virus is being suppressed in any HIV patient, when deciding whether to press charges.

“The fact remains, HIV is fatal,” Fontaine told the court. “Life with HIV has improved but it is still fatal.”

For many Canadians, the argument comes down to what they would want in the same situation. Many would agree they should have the right to know what diseases their sexual partners has before deciding whether to engage in sex, and that to not reveal one’s HIV status to a partner is just wrong.

But Symington argues there is sometimes a distinction between what society sees as ethically bad behaviour and what it decides is criminal behaviour.

“Just because you’d like to know your partner’s HIV status doesn’t mean that it should be criminal not to disclose it. The criminal law is the strongest, most blunt tool of our society and it should really be reserved for the most blameworthy cases,” she says.

Sexual assault and aggravated sexual assault are serious charges and can result in heavy prison sentences, Symington notes. Those convicted must also be registered as sex offenders.

She says her group knows of the case of one man living with HIV who was charged with aggravated sexual assault for performing oral sex a few times on his ex-partner.

“The risk of HIV transmission is so low in oral sex, scientists even have a hard time quantifying it. So to equate that with an aggravated sexual assault, which is usually the charge, we use for a violent rape case, doesn’t seem like a proper equivalency,” says Symington.

The Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network would like the Supreme Court to either clarify what is meant by “a significant risk of transmission” or create a new test to help court and police distinguish between low-risk behaviour and reckless behaviour.

The Crowns of Manitoba, Quebec and Alberta would like the court to make the situation clear and declare that valid consent to sex requires disclosure of HIV status -- regardless of the accused's viral status or whether condoms are used.

The court will issue its final ruling some time this fall.