Prime Minister Stephen Harper was “horrified” by the newly released surveillance videos in the Ashley Smith case and has ordered Correctional Service of Canada to co-operate with the Ontario inquest into the troubled teen’s prison death, CTV News has learned.

Sources also say there are 60 hours of video footage showing 109 incidents where correctional staff used force against Smith before she killed herself in a Kitchener, Ont., prison cell more than five years ago.

At a coroner’s inquest Wednesday, only about 43 minutes of footage was released.

A source who viewed the tapes said Smith resembled a “three-year-old craving attention” but the abuse she suffered was “relentless” and constant.

The tapes prompted Harper to tell officials that “the poor girl has suffered enough,” CTV’s Ottawa Bureau Chief Robert Fife reported Thursday night.

Publicly, Harper described Smith’s Thursday as a “terrible tragedy” that has revealed an unacceptable way of treating prisoners with mental illness.

One of the surveillance videos made public at the coroner’s inquest shows Smith strapped down to a gurney at Montreal’s Joliette Institution and forcibly tranquilized by a nurse.

In another video, a subdued Smith is seen with a spit hood over her head as guards duct-tape her arms to an airplane seat during a transfer from a Saskatoon prison, and threaten to duct-tape her face.

“Obviously there’s information that’s come to light that is completely unacceptable to the way Corrections Canada is supposed to do business,” Harper said in the House of Commons Thursday.

The government will look at what additional investments need to be made in mental health aspects of its Corrections policies, he added.

Smith, 19, choked herself to death in her cell at the Grand Valley Institution in Kitchener, Ont., in October 2007 as guards looked on. First jailed at 15 for throwing crab apples at a postal worker, the Moncton, N.B. teen’s sentence was extended for numerous in-custody incidents. Eventually, she was transferred 17 times among nine institutions in five provinces.

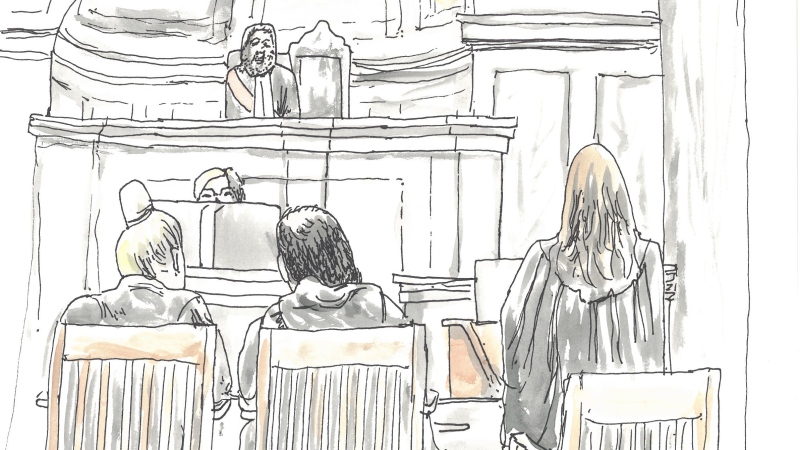

The inquest in Toronto has been plagued with procedural issues as the Correctional Service of Canada argues the Ontario coroner , Dr. John Carlisle, doesn’t have the jurisdiction to delve into how Smith was treated in federal prisons in other provinces.

The Opposition accused the government Thursday of trying to block the coroner’s efforts to get at the truth at the inquest, which has been adjourned until Nov. 13.

“In the coroner’s inquest that is now underway the federal government has consistently taken the position that the jurisdiction of the coroner has to be restricted, that they can’t look at videos,” Liberal Leader Bob Rae told the Commons.

“They’ve consistently taken a position that has been antithetical to the interests of the truth and the interests of the family,” added Rae.

But Harper said the government won’t interfere and will let the legal arguments get resolved at the inquest.

Julian Falconer, the lawyer representing the Smith family, said Thursday it’s important to show the disturbing surveillance footage of her death to reveal the realities of life behind bars for those struggling with mental illness.

The chilling videos from the final months leading to her death prove the Corrections Service of Canada is not equipped or prepared to deal with the mentally ill, he said.

"We have a prison system that is simply incapable of managing the mentally ill, and the most recent statistics -- literally in the last two weeks, by the correctional investigator -- show us that the number of self-harming incidents by inmates has more than doubled in the last few years and that women disproportionally represent those numbers," Falconer told CTV's Canada AM.

Falconer said Smith's case is not an isolated incident. The mentally ill are often subjected to brutal conditions because prison staff simply aren't equipped to handle them, he said.

"When people see these videos they mustn't think to themselves: 'This is unique to Ashley Smith,'" Falconer said. "I can tell you I represent other families; this is happening to other people -- people's sons, wives, daughters. They end up in the system for reason of mental illness."

Falconer had previously told the inquiry that a psychiatrist prescribed the injections given to Smith at Joliette over the phone, based on information provided by a nurse. He said Smith was given “chemical restraints” five times in seven hours. Falconer is calling for both the psychiatrist and the nurse to testify at the inquiry.

Kim Pate, an inmate advocate with the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, said she was horrified when she saw the videos. She had been in contact with Smith in the months leading up to her death, and realized watching the footage that Smith wasn't aware of her rights as a prisoner.

"She didn't even know what they were doing to her in those instances was illegal, it's completely unlawful... you're not allowed to duct-tape someone to a chair in an airplane because they're saying they want to go to the bathroom and they're trying to undo their seatbelt,” Pate told Canada AM.

“You're not permitted to forcibly inject someone five times because you don't like them talking to you or requesting things, whatever it was they were upset about," said.

"The write-up by Corrections was that she was out of control and a danger to herself and staff, and the videos show quite the opposite."

The surveillance videos were released publicly for the first time Wednesday after the Correctional Service of Canada lost its battle to keep them out of the inquiry. The agency had argued that it is outside the inquiry’s scope to be looking at operations within the federal prison system.

Carlisle is tasked with examining the effect of long periods of segregation, as well as the effect repeated transfers had on Smith’s deteriorating mental state.

He also wants to probe how Smith was treated in the months leading up to her death.

Both Falconer and Pate said they hope the videos of Smith’s final months lead to a higher level of accountability for corrections staff when dealing with inmates who are mentally ill.