MONTREAL - Canada's legal system waded into uncharted territory as lawyers debated what punishment to hand the country's first convicted war criminal Tuesday.

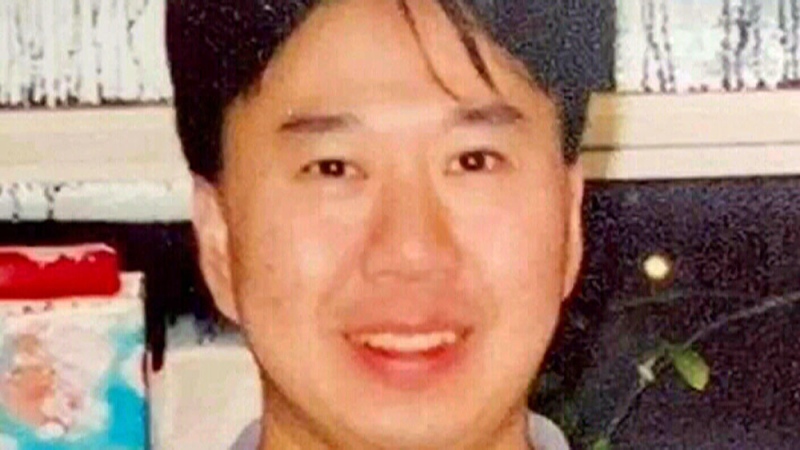

Prosecutors assigned to the case demanded a life sentence for Desire Munyaneza, a Rwandan man convicted of murdering and raping ethnic Tutsis during one of history's worst atrocities -- the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

Crown lawyer Pascale Ledoux argued that after having raped dozens of women, participated in slaughtering hundreds inside a church, and used sticks to beat children tied in sacks, Munyaneza, 42, deserved the maximum punishment possible.

Legal experts say the case could be precedent-setting not only in Canada, but also for other countries grappling with similar examples of war criminals seeking sanctuary within their borders.

Munyaneza was arrested by the RCMP at his Toronto-area home in 2005. He was found guilty in May, and Quebec Superior Court Justice Andre Denis is to hand down a sentence on Oct. 29.

"In light of the horrible circumstances of this case, the only logical conclusion is the maximum penalty," Ledoux said.

The incidents date back 15 years to the genocidal slaughter of 800,000 Rwandans -- mostly minority Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Munyaneza was found guilty of seven charges related to genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity for his role in massacres and rapes near Butare, Rwanda, between April and July of 1994.

Munyaneza is the son of a wealthy businessman from the area.

The verdict made Munyaneza the first person to be convicted under Canada's Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act, enacted in 2000.

Munyaneza was already facing the prospect of a life sentence, but with a lack of jurisprudence in war-crimes cases, lawyers argued over whether he should be eligible for parole.

Legal observers -- both here and abroad -- are keeping close watch as Canada's costly prosecution of Munyaneza will serve as a blueprint for other countries entering similar prosecutions.

"It's part of an emerging global system which says: 'Use the big international courts for the mega-trials of the senior leaders, but recruit the efforts of the domestic courts to help ensure the many perpetrators who flee abroad after the events don't live in impunity,"' said Bruce Broomhall, an international criminal-law professor at the Universite du Quebec a Montreal.

Genocide survivors are also eagerly watching the Munyaneza case, says Richard Nsanzabaganwa, a lawyer and former human rights investigator in Rwanda.

"For them it is very important because it is a conclusion of a whole process through which they have remained so anxious to know whether or not here in Canada you can be protected by Canadian laws prosecuting international crimes," said Nsanzabaganwa, who is also president of the Canadian Association for the Rwandan Tutsi Genocide Survivors.

The defence is appealing the verdict. A hearing before the Quebec Court of Appeal isn't likely to happen before the fall of 2010.

Bound by Denis' verdict, Munyaneza's lawyer Richard Perras could only argue that the judge had some discretion in determining the number of years before Munyaneza was eligible for parole.

He said outside the courtroom that he was hopeful that Denis would reduce the eligibility time to about 20 years and potentially shave a few years off the mandatory life sentence.

But Perras added his client still firmly believes he is innocent.

"We've gone to appeal, we pleaded not guilty (to begin with), nothing has changed," Perras said.