The super-sized successor to NASA’s legendary Hubble Space Telescope is more than a year away from deploying its massive two-storey tall, gold-plated mirrors in the harshness of deep space. That’s why scientists are busy freezing the US$9 billion, 6,200 kilogram spacecraft to see if they can break it here on Earth.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) -- the largest space observatory ever built -- is expected to help scientists piece together the earliest moments of solar systems and delve deeper than ever into our expanding universe.

It’s three times wider than the Hubble. It’s so big that it will need to be folded up to fit in the rocket that will take it beyond the Earth’s atmosphere, hopefully in October 2018. Its shield is the size of a tennis court. And NASA expects it will spend between 5 and 10 years orbiting the sun, not the Earth, at a distance of 1.5 million kilometers.

Experts say the telescope’s ability to peer deeper into space could revolutionize our fundamental understanding of astronomy. They are also very worried that something could break once it’s up there. So they’ve put it in a massive freezer to see what happens.

“If there is a problem, we want to know about it right now,” York University physics and astronomy professor Paul Delaney told CTV News. “One side of it facing away from the sun is going to be literally at the temperature of space. The other side facing the sun will be gently cooked at a couple of hundred degrees.”

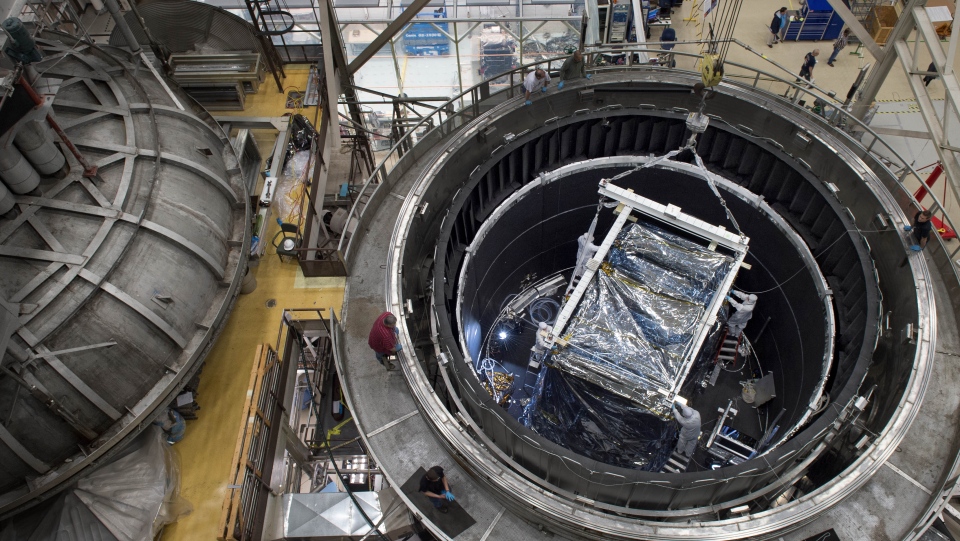

Everything on the JWST, including the Canadian-made Fine Guidance System and imaging equipment, will have to brave the bitter chill of near-absolute zero, which is about -273 degrees Celsius, before launch.

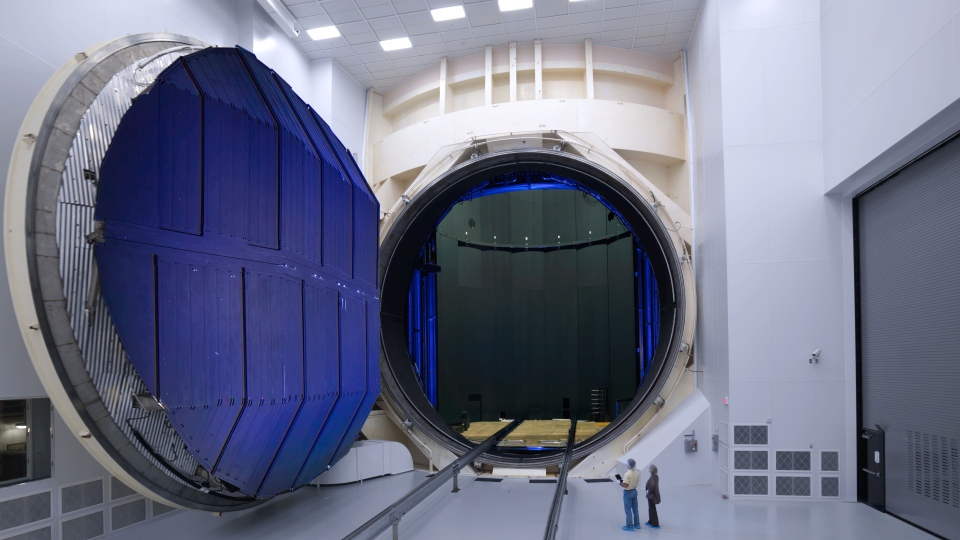

To test this, the JWST was sealed in the historic Chamber A at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas on July 10. The monolithic room behind a 36-tonne door was originally used to test the Apollo spacecraft. It takes 10 days to suck all the air out, and about a month to get the temperature low enough to conduct the tests.

In space, the telescope must be kept extremely cold in order to be able to detect infrared light from very faint, distant objects. Specialized cameras inside Chamber A will track the physical position of the JWST’s hardware to monitor how it moves as the temperature drops. Making sure the JWST’s spectacular array of mirrors can focus light properly will be essential.

NASA learned the importance of ensuring their telescopes have perfect vision before launch the hard way when Hubble first went into orbit in 1990. Its early images were unfocused due to a slight flaw in its primary mirror. Astronauts had to add corrective optics, essentially giving the Hubble a set of eyeglasses.

“They have taken a little more time to make sure this instrument really is as foolproof and as flawless as we can make it,” Delaney said. “We’ll know the answer to all our engineering excitement just about 15 months from now.”

He hopes the tests will assuage NASA’s anxiety so the JWST can go to work helping him better understand the universe as soon as possible.

Anticipation for what the Hubble successor will capture has been building for over a decade. Unlike the Hubble’s optical setup, the JWST will use infrared technology that Delaney says will allow us to see exoplanets, planets beyond our own solar system, in their earliest moments of formation.

“To be able to piece together both the early moments of a solar system and the cosmological implications of our expanding universe, those are the two really key areas that everybody is excited about for James Webb,” he said.

The JWST is also said to be able to see through dust and gas far better than Hubble. The combination of its massive 6.5-meter aperture and infrared spectrum vision have proved so tantalizing for scientists that books about the JWST have been published prior to its launch.

“This is potentially a game-changer,” Delaney said. “If it is operating properly for four or five years, (it) could literally revolutionize many of the fundamental questions in astronomy. Many of which have only been asked in the last 10 or 20 years since Hubble.”

CANADA’S CONTRUBUTION

The Canadian Space Agency (CSA) is providing a number of devices for the JWST, but Delaney is careful not to overstate the significance of Canada’s involvement in the project.

“I don’t think it would be fair to say we are one of the principal countries involved in the James Webb,” he said. “But of course there are many scientists from Canada, and around the world, who are on multi-national teams that are being led out of the U.S.”

CSA is providing the JWST’s Fine Guidance Sensor, as well as one of the telescope’s four science instruments, called the Near-InfraRed Imager and Slitless Spectrograph.

Both components were designed, built and tested for the CSA by COM DEV International in Ottawa and Cambridge, Ont. The Université de Montréal and National Research Council Canada made technical contributions.

The Fine Guidance Sensor consists of two identical cameras that are critical to the JWST’s ability to locate celestial targets, and stay pointed in the right direction while collecting data.

“It’s so that we can latch onto a star and be able to keep the telescope pointed precisely,” Delaney explained.

With a report from CTV’s John Vennavally-Rao