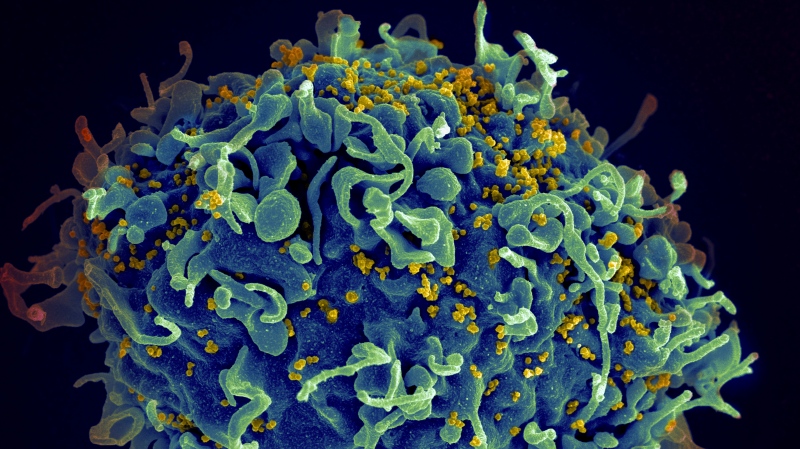

Hundreds of scientists are gathering in Washington, D.C., on Tuesday for an international summit on gene editing, a technique that has the potential to eliminate genetic diseases by altering or deleting sections of DNA in living cells.

The upsides of the process are immediately obvious when looking at cases like one-year-old Layla Richards, who was cured of leukemia earlier this month after being treated with "designer" immune cells that were genetically engineered to reverse her cancer.

This life-saving process is only about five years old, but already is being used to create things like disease-resistant plants and mosquitoes that are incapable of carrying malaria.

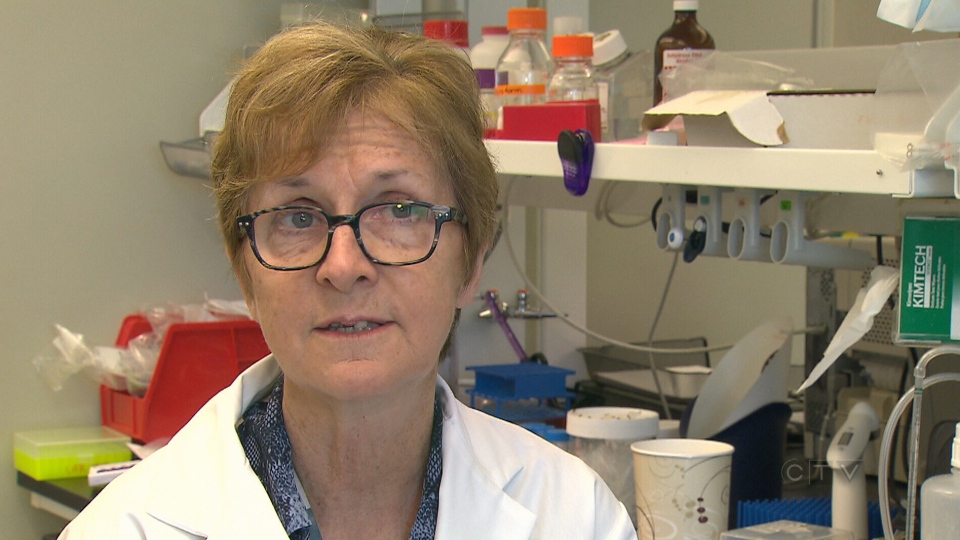

"It is just the speed and efficiency and the real power that is still just being developed that really is a game changer,” said Janet Rossant, a genetic scientist at the hospital for sick children in Toronto who will be attending the summit.

For years Rossant’s team has been modifying mice to allow them to carry human diseases. They used to create mutations one gene at a time, but using something called the CRISPR/Cas9 technique, her team is able to produce the animals at a much quicker rate, making their research more efficient.

But it’s the consequences of such a powerful technique that the world’s geneticists will discuss at the three-day International Summit on Human Gene Editing this week.

"Is it OK to fix a bad disease? And if that’s OK to do that, what about enhancing human potential?” said Rossant. “Where do we draw the line?”

Some scientists in the U.K. have already asked permission to edit human embryos and “fix” genetic illnesses. Chinese researchers also recently edited discarded embryos, trying to eliminate a disease called thalassemia -- an attempt that was unsuccessful in some cases.

Cases like these are causing groups like UNESCO to call for a moratorium on human germ line testing until the effects of the technique are better understood.

Kerry Bowman, an ethicist and University of Toronto professor, says gene editing has the potential to alleviate suffering, but also the potential for harm.

"The children born from this would then pass on those changes to their children, their children and their children,” Bowman said. “So the human germline is shifting. This would be permanent change to the human story.”

One of the goals of the Washington summit will be to create a guideline for scientists around the world to follow while editing genes.