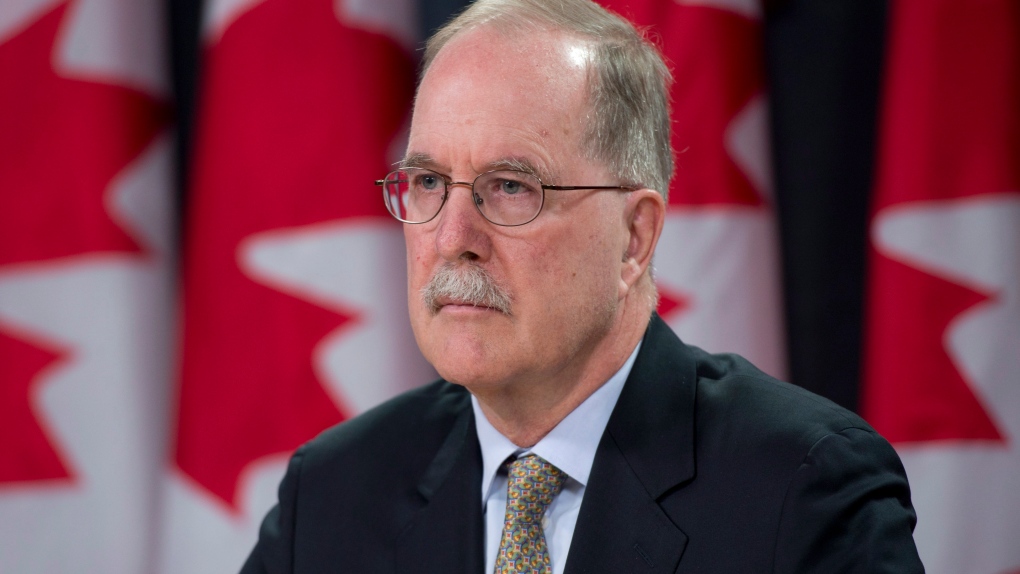

Canada’s official languages commissioner says his office received hundreds of complaints about bilingualism last year, which included concerns about the appointment of a unilingual auditor general.

In his annual report, released Tuesday, Commissioner Graham Fraser said his office investigated 518 complaints. The majority, or 341 complaints, were about communications with and services to the public. These services were either in person, in writing, or services at airports.

Fraser noted that an issue of particular concern in 2011-12 was the appointment of an English-only speaking auditor general, which led to 43 complaints.

The outcry over the appointment, Fraser said, “has shown that both English- and French-speaking Canadians have greater expectations. The bar has been raised. Canadians expect senior officials across the country to be bilingual.”

In his report, Fraser says the federal government has a role to play in ensuring that there is a larger pool of bilingual candidates for senior positions. He recommends the government create scholarships and exchange programs for students who want to study a second language, noting that Ottawa made a similar move to retain students and researchers by creating the Canada Research Chairs and the Millennium Scholarships.

Fraser singled out other recent investigations, including a 2010 audit of Air Canada that concluded the carrier needed “to change its organizational culture and thoroughly review its planning for the provision of bilingual services.”

His office submitted its report on the audit in 2011, which included 12 recommendations, and noted that Air Canada developed an action plan to address his concerns. However, Fraser’s office continues to receive complaints about the airline, which he says must step up its timeline to implement his suggestions.

Fraser also noted that while both English and French appear to flourish in the National Capital Region, an audit found that “the bilingualism of businesses in tourist areas is Ottawa’s best kept secret.”

His department’s observations found that “while there is substantial bilingual capacity for visitors to Canada’s capital, it is often invisible.” Fraser recommends simple fixes, including greater use of a bilingual “hello, bonjour” greeting to signal that service is offered in both languages.

Fraser pointed out that as Canada heads toward the 150th anniversary of Confederation in 2017, more should be done to ensure that “Canadians, whether bilingual, unilingual or multilingual, are proud of the fact that English and French can be heard in their neighbourhood, their town or their region.”

In addition to the language-study recommendations for students, Fraser also recommends that Industry Canada “create a support mechanism” for Canadian businesses to develop their capacity to operate in both official languages.

In his conclusion, Fraser said Canada can only realize its potential when it fully meets the needs of its two largest language communities and fosters dialogue between English- and French-speaking citizens.

“Linguistic duality is one of Canada’s core values, a part of its DNA,” Fraser writes. “It is up to all Canadians to talk about it, take full advantage of it and celebrate it.”