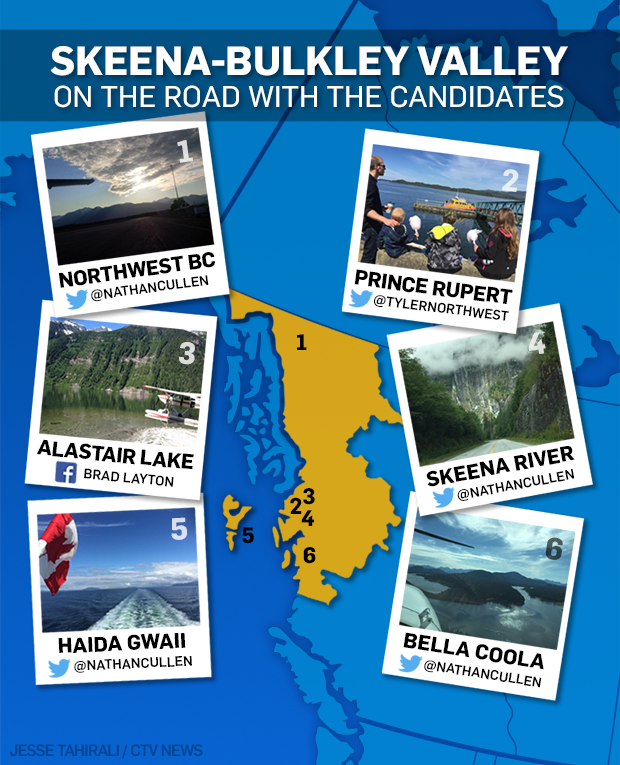

It’s roughly the size of Norway and three times larger than England. Spanning all of northwestern British Columbia, the Skeena-Bulkley Valley riding is intimidating terrain for a potential member of Parliament.

The area encompasses coastal communities such as the Haida Gwaii, industrial towns like Kitimat and Terrace, as well as remote aboriginal villages.

Its isolation means limited cellphone service and expensive travel costs.

Measuring 327,275 square kilometres, it’s the largest riding in British Columbia and the seventh-largest in the country.

"It's a very large and very spread out riding," said Nathan Cullen, the NDP candidate who has served as MP since 2004.

"Some of the large ridings, they have a large percentage of population living in one or two towns. There's no town here like that. You can go from a forestry town to a coastal First Nations village. The realities are different even though they're in the same riding."

With the election now in full swing, parties are getting up to speed in an area that has one of the fewest people per square kilometre in the country.

Aside from the NDP incumbent, Brad Layton is running for the Liberals, Tyler Nesbitt represents the Conservatives, and the Green Party has yet to announce a candidate.

Nesbitt declined an interview request, instead sending a written statement acknowledging the amount of travel he has done in canvassing the area.

“I’ve logged lots of miles to knock on doors across the riding,” Nesbitt said.

The candidates will face unique hurdles -- criss-crossing the area consumes time and money, and not just in simple ways like paying for a flight.

A single ferry trip to the island community of Haida Gwaii, which only runs one way once a day and takes seven hours, costs $50 per person and a minimum of $165 per standard-sized vehicle. Cullen says a recent visit to the island for a campaign stop set him back $600.

Certain communities aren’t accessible by commercial ferries. For those, candidates have to fly in on floatplanes, which can lead to thousands of dollars in charges.

Cullen says he tries to save money by avoiding hotels and meals in restaurants. He does that by staying with supporters, which he believes helps build stronger community bonds.

‘It takes so much time’

The sheer cost of running a campaign can be daunting for prospective candidates.

"It’s definitely a challenge,” said Layton. “We didn’t have a big buildup of funds in the North for the campaign for the Liberal Party.

“If I want to drive up to Dease Lake, that’s three or four tanks of fuel and a few hundred dollars. The cost of even driving to a place eats up budgets.”

Maintaining your visibility as a candidate can add to costs.

Cullen has four campaign offices spread throughout the area and tries to visit as many of the communities as he can.

In the previous election, Cullen's campaign spent just over $70,000. He expects campaign spending to hit $85,000 this year due to travel and inflated real estate costs for the campaign offices.

Inflated real estate costs, in cities such as Kitimat and Terrace, can make it expensive to rent a campaign office. Layton says he hopes to have one campaign office but in certain communities, due to their size and commercial space, some don’t have any free space for a campaign office.

When plotted out, to travel from Bella Coola, one of the riding's most southern communities, to the top of the riding by car would take 20 to 25 hours of solid driving.

The isolation of the riding also leads to odd scenarios. Layton says getting election signs can be a hassle.

Typically, they are sent from the respective party’s headquarters to the riding in question.

In metropolitan areas such as Toronto or Vancouver, the signs are easily mailed to the candidate's campaign office.

In the Skeena-Bulkley Valley riding, those signs have to be sent from party headquarters to Vancouver and then separately shipped when they reach the province, meaning candidates can go extended periods without new election signs.

In the first week of the election, while candidates in urban areas rushed to place their signs, candidates in Skeena-Bulkley Valley had none.

Cullen estimates it took about a week before his campaign team had their first shipment of 6,000 signs.

Layton says his campaign has just ordered signs and hopes to have them shortly.

Door knocking exercise

The stereotypical door knocking experience is different as well. When candidates get out of the more developed areas, such as Kitimat or Terrace, large rural properties become the norm.

Cullen says he loses 10 pounds in weight, purely from going door-to-door to meet voters.

Dress shoes are replaced by running shoes and candidates get used to spending days only visiting a handful of properties.

“You get to some properties, and it’s 75 steps from the end of the driveway to the front door. Sometimes there’s no one there so you have to walk all 75 steps back and you've lost that time,” he says.

Another challenge is appealing to a wide range of voters over such a huge expanse of land. Cullen has been adamantly opposed to the Northern Gateway pipeline project, like many of the voters. However, he admits there are few other issues that unite the riding.

"There's very little that I can say that consistently applies to everybody," says Cullen. "There's no generalizations that I can really make about the region. You have to be pretty community-specific."

Layton agrees.

"You’re dealing with different issues right across," he says. “It’s not like an urban area, which might be a certain amount of square blocks, where a lot of the issues are the same thing. Fort St. James has very different issues from Rupert.”

A few weeks into the election, the sheer size of the riding still appears to be hindering candidates.

"I’ve seen some signs but they’ve all been for (Nathan) Cullen. No Conservative or Liberal signs have been put up in my area at all,” said Shannon McPhail, a fourth-generation resident of Hazelton, a small town near Terrace.

McPhail says the region may have a reputation as being against development, citing the backlash against the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline, but residents do support projects that create work.

"We want development. We are a development region,” she said. “But we aren’t willing to sacrifice the things that have sustained us."